Abecedario de Juárez by artist Alice Leora Briggs and photojournalist Julián Cardona is an illustrated glossary of narcolenguaje and a collection of stories from the streets of Ciudad Juárez.

You can’t believe it. It is difficult to believe it even when you see it happening right in front of you. You see it, but you can’t make sense of it en caliente (in the heat of the moment). You say to yourself, “They are executing someone. They are killing someone.”

These are the words of a man named Chapa, who witnessed an execution on a city street while traveling toward El Paso out of Ciudad Juárez in 2008, shortly before the city became the “murder capital of the world.” Chapa’s story was recorded by Mexican journalist and photographer Julián Cardona in 2012. It is just one of the narratives contained in a book published this year by Cardona and Tucson-based artist and writer Alice Leora Briggs, Abecedario de Juárez: An Illustrated Lexicon (University of Texas Press).

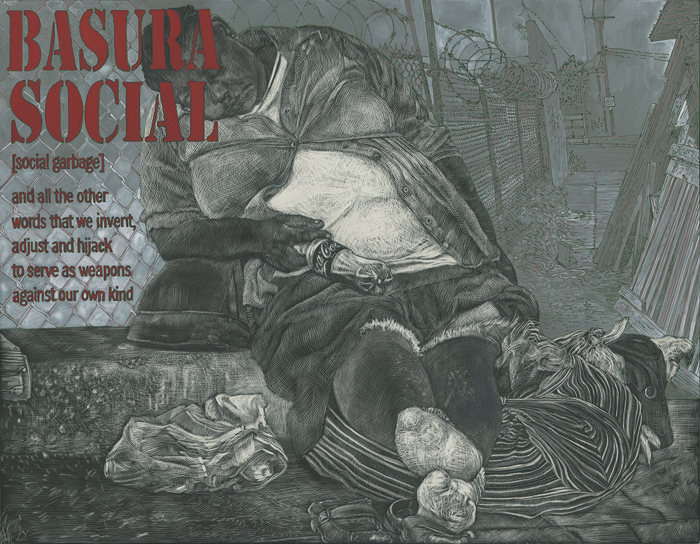

Partly an illustrated glossary of narcolenguaje, partly a collection of stories from the streets of Juárez, the text moves between alphabetical listings of slang terms related to the drug trade and first-hand accounts of murders, disappearances, wayward sons, and innocent victims.

“It was much like the structure of Juárez,” Briggs tells me one afternoon on Zoom. “Where it all seems like you might be able to predict what would happen next, but as soon as you think that—all is lost.”

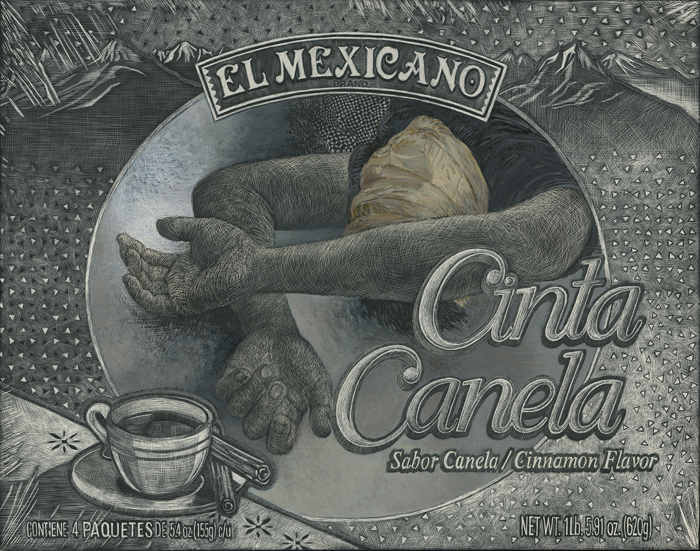

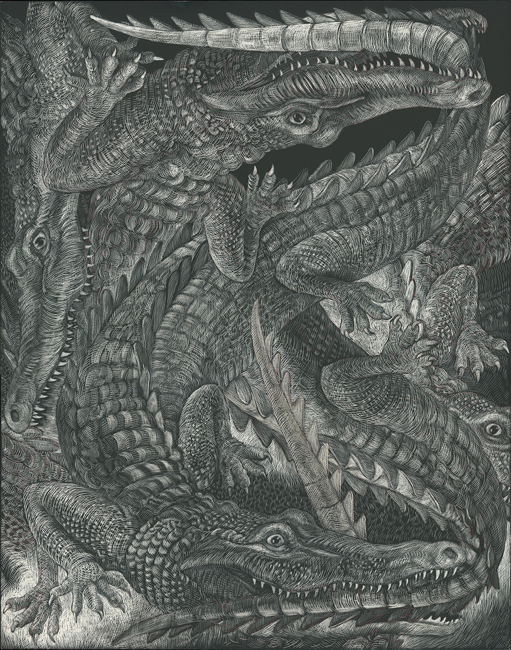

The entries are accompanied by dark, sometimes gruesome, sometimes humorous drawings largely executed in sgraffito (Italian for “scratched”). Briggs’s alphabetical illustrations for the Juárez glossary draw comparison to Hans Holbein’s Alphabet of Death (1523-24), but instead of dancing skeletons, they feature murder victims, corrupt cops, and crime scenes (there are a few dancing skeletons, too). The darkly satirical political lithographs of José Guadalupe Posada are clear predecessors as well.

Briggs, who started visiting Juárez in 2007 while collaborating with author Charles Bowden (who passed in 2014) on his 2010 book Dreamland: The Way Out of Juárez, works from photographs, drawings, and historical material. The works from the Abecedario, recently the subject of an exhibition at Evoke Contemporary in Santa Fe, sometimes incorporate figures from northern European Gothic sources, fitting for the kinds of primal and punitive violence portrayed: hangings, decapitations, severed limbs. In one illustration of a cluttered junkyard, two cherubs hold aloft a banner emblazoned with the words “near impunity.”

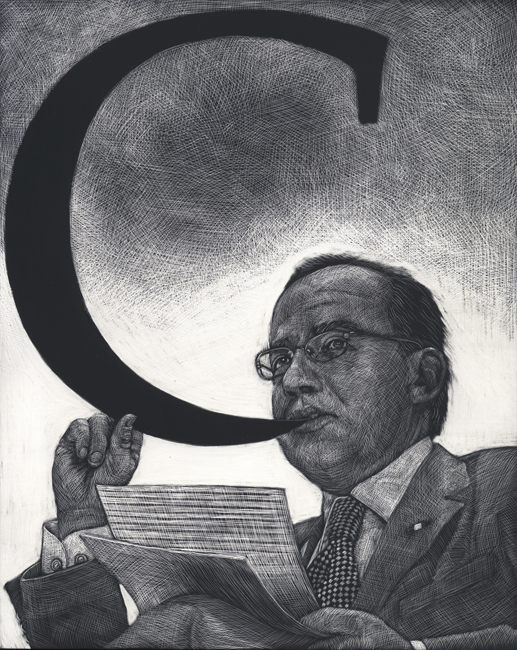

The vocabulary entries of the Abecedario cover the slang terms that arose out of the drug trade since the 1990s, with a particular focus on the years 2006 through 2012 during the administration of Mexican president Felipe Calderón. Days after taking office, Calderón declared a “war on drugs” and sent thousands of federal troops to the streets of Juárez, where the rates of violence skyrocketed.

The book contains accounts of innocent civilians apprehended, interrogated, and tortured by the military for alleged drug crimes. Calderón callously termed those innocents killed in the course of the “war” simply baja colateral, or “collateral damage.” Briggs’s illustration for the letter “C” shows Calderón with the letter emerging from his mouth, “his serpent’s tongue,” as she calls it.

“Human beings are so amazing in how they can adjust to almost anything,” Briggs says. “There was this incredible vocabulary that exploded in Juárez during the Calderón administration, people just trying to grapple with all of this violence. I was really focused on that.”

Together, she and Cardona drove around the city, visiting morgues, rehab centers, and execution sites. “Julián, as a photojournalist, and I, [we] were both coming from visually centered backgrounds,” Briggs says. “But he began interviewing his fellow citizens, and he always was talking about these stories.”

Briggs and Cardona started working together on the Abecedario in 2012 after discovering that they had been working on similar projects independently of each other. “It was actually Chuck Bowden who invited us to dinner, and he said, ‘You know you guys really need each other,’” she explains.

They had been working on the book for eight years when Cardona suddenly died in 2020. Briggs, with the help of editors, took on the job of the final rewriting and editing of the book.

“It was a book I really did not want to write—I wanted to focus on the visual aspects of the book,” she tells me. But with Cardona’s insistence on the words, on the narrative, echoing in her head, “My resistance just finally broke down. But I’m so glad that it turned out that way. I learned so much from him.”

Cardona was born in Zacatecas, moved to Ciudad Juárez as a child, and lived there for the rest of his life, even as journalism became an increasingly dangerous profession. In a 2012 interview, he explained his motivation for dedicating himself to the city: “It’s an important story, how a city becomes the most violent city on earth.” (Juárez has since dropped from the number one rank for homicides per 100,000 residents, but remains high on the list.)

Briggs, who was born in Texas and now lives in Arizona, concurs in our interview, saying, “I feel like people need to know what happened here. It needs to be talked about. It’s not easy.”