From pure intuition to a pricing calculator, artists and gallerists across the Southwest reveal how they actually put numbers on their work.

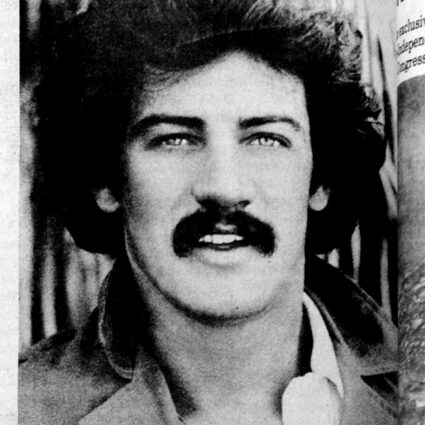

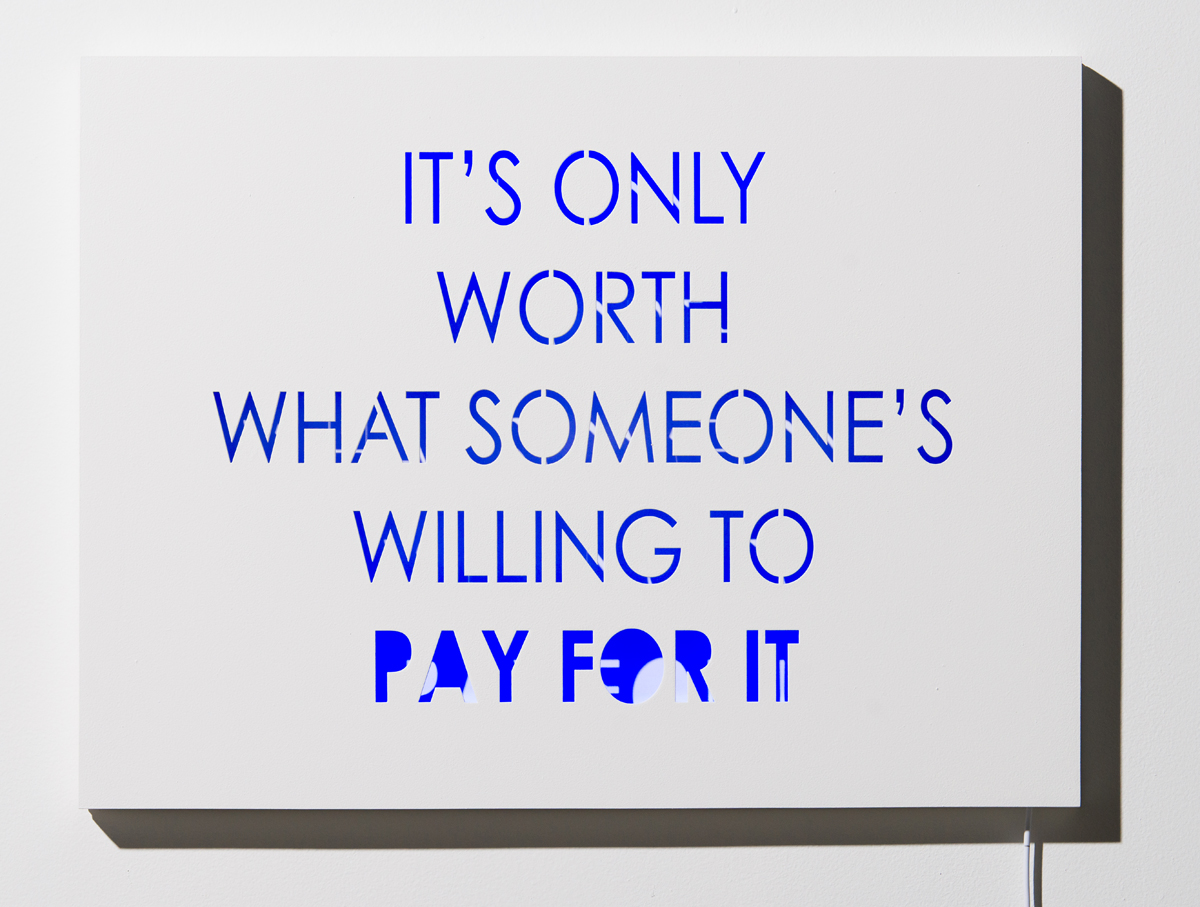

Artist Craig Randich has vivid memories of his first solo exhibition at Eye Lounge in Phoenix, where he showed several text-based artworks capturing the commercialism and competitiveness of the contemporary art market through the words of artists and art dealers. For example: “I am better than you.”

It was 2010, and the Arizona-based sculptor recalls his mother leaning in during the opening reception, whispering a simple question in his ear: “Are you going to be able to sell this?”

I have to be making artwork, otherwise I don’t feel complete, whether it’s selling or not selling.

“No,” he whispered back. “I have to be making artwork, otherwise I don’t feel complete, whether it’s selling or not selling,” Randich recalls explaining at the time. Still, he notes that “all artists like to have their work sold, for the paycheck and for the adulation.”

Today, artists in the Southwest and beyond are wondering how to price their art, especially amid rampant changes in the art market fueled by everything from gallery closures, to the growing influence of technology, to broader economic flux.

On the one hand, art professionals offer various formulas for determining the price of an artwork. On the other hand, artists have strong feelings about the value of their work.

“We have very emotional connections to our artworks, like they’re our little babies,” says Randich, who has also spent several years as a gallerist and art dealer.

“Pricing is completely subjective,” reflects co-founder Tonya Turner Carroll of Turner Carroll Gallery in Santa Fe, who explains that setting the price for any artwork comes down to using “benchmarks and intuition.”

It’s better to price things conservatively, because you really can’t go back.

Referencing her initial work with famed Pussy Riot founder Nadya Tolokonnikova, Turner Carroll remembers asking the activist and artist about her goals, and whether she would rather “establish a wide collector base or hold out for higher prices.”

“We went with lower prices because she wanted to get the artwork into people’s hands,” says Turner Carroll, who recalls initially selling Tolokonnikova’s prints for $350, then $700 after the artist gained more traction. Today, of course, you’ll find her prints listed for far more on Artsy.

Turner cautions against setting prices too high at the outset, a practice she’s seen some gallerists undertake in an effort to cash in on a trendy artist’s cachet. “It’s better to price things conservatively, because you really can’t go back and lower it without having collectors and artists feel like you’ve devalued the work.”

Likewise, Randich encourages artists to “price your work as reasonably as you can starting out so it can be acquired by collectors,” he says. “I’m not talking about top-tier collectors; I mean the young collectors who are out there who will be building their collections over time.”

Carl Bower, a Colorado-based photographer and Pulitzer Prize finalist whose portraiture has been featured in Southwest Contemporary, remembers trying to price his own documentary imagery for an exhibition during his mid-twenties.

I think my pricing was a little bit fear-based because I really didn’t know how to do that.

“I don’t have an MFA and I wasn’t familiar with these things so there was this sort of panic,” Bower recalls. “I think my pricing was a little bit fear-based because I really didn’t know how to do that; I was taking a personal approach instead of treating it as a business decision.” Today, he’s confident charging prices that reflect “an evolution in the complexity of my work.”

What to charge for artworks is a common question among emerging artists, according to Nevada-based artist Rossitza Todorova, a professor of art at Truckee Meadows Community College in Reno. “You can devalue your work if you price it too low, but you can scare people away if you price it too high when you’re just starting out,” Todorova explains.

One resource Todorova mentions to students is an art pricing calculator available through the online gallery PxP Contemporary. The tool suggests three different approaches that incorporate a variety of factors such as the stage of an artist’s career, the cost of materials, and the time it takes to make the work.

But doing the legwork is just as important.

“It takes some research,” Todorova says. “You have to look at a lot of art and spend time in a lot of different spaces to see what art is selling for, so you really begin to understand your own local market.”

Experts agree that artists can increase the prices of their work as they have more exhibitions, place work in more collections, and become better known. In Randich’s case, he’s been able to raise the prices of his work by 150 percent over time.

It’s best not to raise your prices more than ten percent at a time.

Just beware of escalating your prices too quickly, cautions Turner Carroll. “It’s best,” she says, “not to raise your prices more than ten percent at a time.”

For artists who find they need to quickly pivot on pricing, perhaps because a gallerist has wildly inflated the cost of their work or they’ve experienced a life change that impacts their financial need, Turner Carroll suggests creating a new series, because those works can more reasonably be sold at a higher or lower price point.

At times, artists have other reasons for changing things up.

After creating three major bodies of work, New Mexico-based artist Anthony Hurd opted to drop their prices for the fourth series. “At the beginning my new series was more experimental, so I decided it was better to get it out there than sell it for more,” Hurd says.

“No art career is linear and no two art careers are alike, so you can’t base what you do on what everybody else is doing,” Hurd adds. “Remember that your work is only worth a certain amount if people want to pay that price for it.”

Most of the time you’re selling a personal relationship, rather than an object.

Whatever you’re charging, experts typically recommend selling work for the same price whether its offered through a gallery or your studio. That way buyers don’t feel taken advantage of and the perceived value of your work remains steady.

“The consistency part is the meat and potatoes,” says Todorova.

Still, selling artwork comes down to more than the price.

“Most of the time you’re selling a personal relationship, rather than an object,” reflects Todorova. “People aren’t really buying art — they’re buying a story, the artist, or the artist’s career path.”

Pricing Tips for Artists

Start accessible.

Price early work reasonably so new collectors can buy in.

Avoid early overpricing.

You can raise prices later, but you can’t lower them without losing trust.

Use benchmarks and intuition.

Know your market, but trust your instincts.

Be consistent.

Keep prices the same across galleries and your studio.

Raise slowly.

Increase no more than about 10% at a time.

Reset with new work.

If you need a major price shift, launch a new series.

Research your scene.

Look at what’s selling locally and online.

Stay business-minded.

Don’t let fear drive your numbers.

Remember what sells.

Collectors buy the story and the artist—not just the object.