Working in her Phoenix studio, artist Gloria Martinez-Granados draws on her experiences as an undocumented immigrant to create textiles and other works countering the nation’s anti-immigrant obsession.

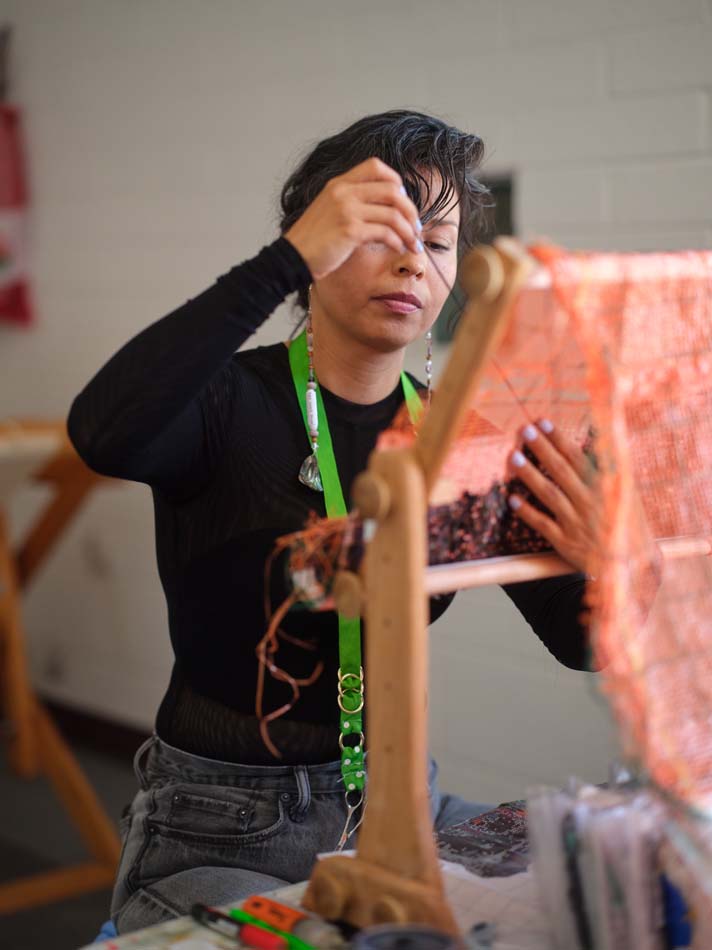

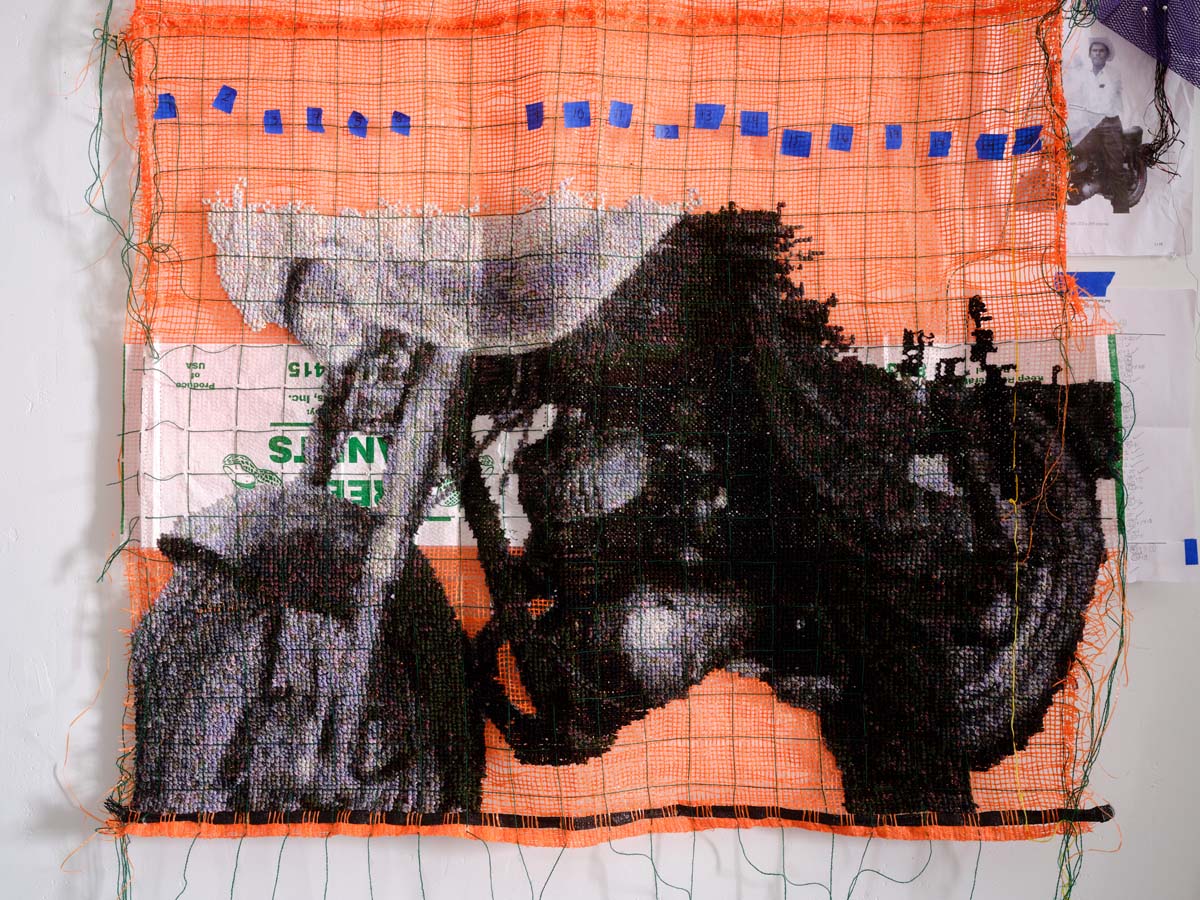

Gloria Martinez-Granados stands over a wood stitching frame set on a small table inside her Phoenix studio one Friday night in early June. An image is taking shape as she repeatedly draws a needle with embroidery floss through a mesh produce bag.

Soft-spoken with a delicate physicality, yet exuding strength and determination, she wields her tapestry in a subtle but powerful act of defiance against fascist forces taking hold, calling to mind the Greek myth of Arachne weaving as she channels the power of art to confront tyrannical power.

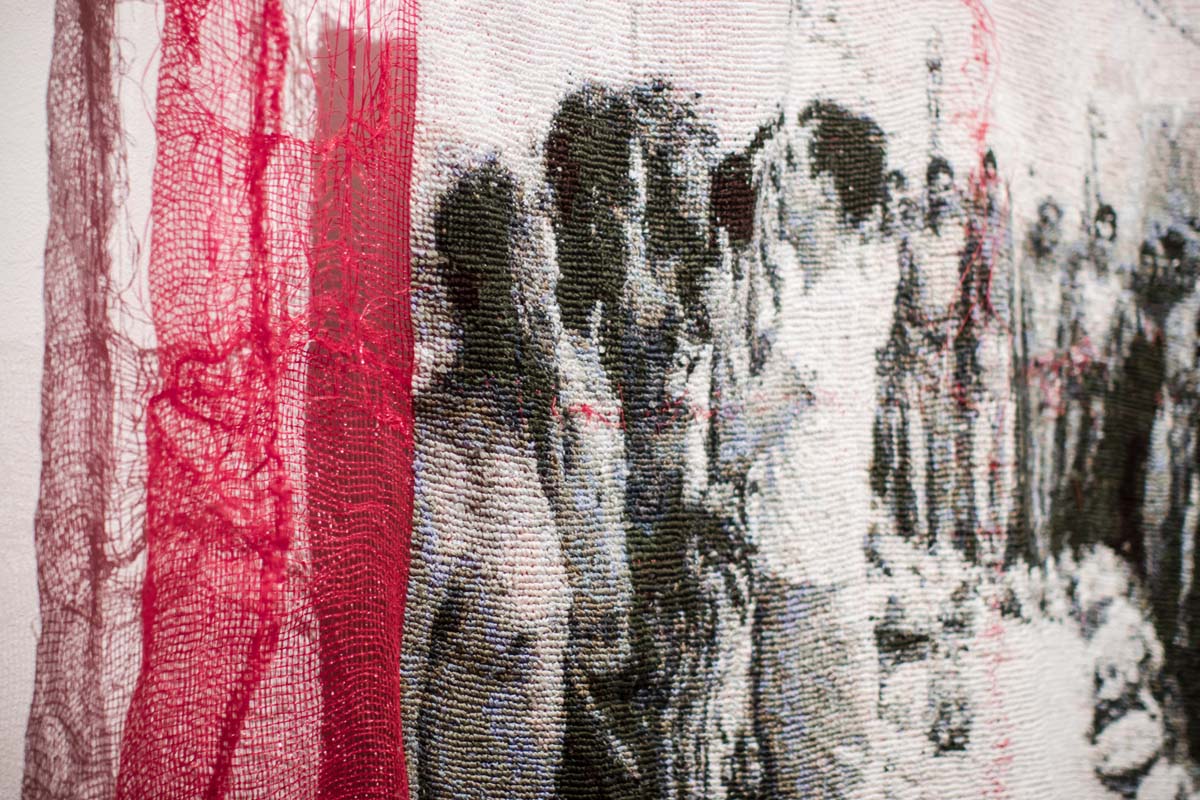

Atop a wood floor loom standing behind her, she sets a long, oblong box containing an earlier work, also meticulously cross-stitched, titled Braceros: Can 48,900 stitches hold history?, which is bound for the exhibition Ya Hecho: Readymade in the Borderlands at Tucson Museum of Art.

The 2023 large-scale textile work depicts Mexican laborers (or braceros) doing seasonal agricultural work in the U.S. Turns out, her father’s father was a bracero—something she learned only after making the piece.

“I’ve taken my work to a historical place, but I’ve also brought it to a personal space,” says the interdisciplinary artist, who was born in Guanajuato, Mexico, then raised in South Phoenix after coming to the U.S. with her family when she was eight years old.

Every two years, Martinez-Granados applies to defer deportation under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the federal program initiated in 2012. Hence, she’s in a perpetual state of legal limbo—despite the fact that both her husband, fellow artist Reggie Casillas, and her daughter are U.S. citizens.

“Making art is a way of healing from the trauma I’ve experienced as an undocumented person,” explains Martinez-Granados, who works within Indigenous traditions including beading, stitching, and weaving, while incorporating contemporary approaches such as video, printmaking, assemblage, installation art, and performance.

“My work celebrates my ancestors,” she says, “and counters the erasure of parts of history that don’t get talked about or taught in school.”

Making art is a way of healing from the trauma I’ve experienced as an undocumented person.

For The Uncertainty of Higher Education (2022) she drew on jewelry-making traditions to suspend 2,000 ID cards from a ceiling inside Phoenix Art Museum. For Patron Terrenal, a 2025 video collaboration with Alonso Parra, she weaved red thread within a rock formation in the landscape, interspersing the site-specific installation with white tags reading “ABOLISH.” Culling from hyper-personal objects of daily life while also interjecting the materiality, processes, and cultural significance of weaving into the vast expanse of geography and geology, Martinez-Granados illuminates the multifaceted realities surrounding immigration, with its intimately personal and familial but also collective and global implications.

Throughout her creative practice, Martinez-Granados examines the ways her identity has been politicized and exploited. To counter that, she’s making work that’s grounded in the land and her cultural heritage. “Our body is the land,” she says, alluding to inflammatory rhetoric about the U.S.-Mexico border and violence committed against Brown bodies. “How can we be kept from ourselves or told we can’t walk across an imaginary border or boundary?”

Part of Martinez-Granados’s creative impulse involves documenting her artmaking, which she often shares on social media or her “Borderless Creative” website. “I’m always documenting things because I’m undocumented; it’s who I am,” she explains. “But I also want people to know that I’m here making art, and help them understand my process.”

Her practice of cross-stitching images onto produce bags began while working at Maya’s Farm in South Phoenix during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nowadays, people bring bags by the studio, where they get added to the artist’s neatly organized array of objects.

“I’m not just making work, I’m drawing attention to these things,” she says.

Beyond exhibiting in mainstream spaces like museums and galleries, Martinez-Granados does private showings at her studio, where the walls are dotted with some of her own small-scale artworks, charts showing embroidery floss colors and stitch counts for works in progress, wooden weaving equipment, and assorted ephemera.

Her studio is part of Rocking S Art Ranch, a creative complex established by artist Patricia Sannit, where Martinez-Granados says she enjoys connecting with other creatives. “Just being able to have conversations with these other artists and seeing what they’re working on is so inspiring,” she says. Within a wider circle, Martinez-Granados draws inspiration from Ai Weiwei, Teresita Fernández, Ana Mendieta, and Amalia Mesa-Bains.

Martinez-Granados recalls that the protests against SB 1070, Arizona’s controversial anti-immigration law enacted in 2010, while she was part of a Latina art collective called Phoenix Fridas, helped to solidify her identity as an artist. Dubbed the “show me your papers” bill, the legislation was assailed for promoting racial profiling and was the strictest anti-immigration law on the books in the U.S. at the time (it was later partially unwound).

Today, there’s an eerily similar context for her work as federal officials across the nation manifest their anti-immigrant obsession. In recent months, reports of masked U.S. agents snatching immigrants at courthouses, churches, homes, and community spaces have escalated, giving rise to a palpable culture of fear. “I’m just trying to survive, I’m not trying to hurt anyone,” says Martinez-Granados, reflecting on the xenophobia and scapegoating she attributes in part to systemic white supremacy and shifting demographics.

As anti-immigrant attacks have intensified, she’s chosen to remain steadfast in publicly sharing the biographical underpinnings of her work. “It’s already out there and I understand the risks of it,” she says. “If it wasn’t for art I wouldn’t be able to function through all these attacks—not just the artwork, the community.”

Although her themes remain constant, it’s apparent that this artist’s practice is shifting over time as she incorporates different media and techniques, hoping to spend more time with beading, video, and land-based work moving forward. “I feel like my work is evolving organically and I’m in the very early stages of pushing where it can go,” she says.

“Art is a different language for communicating with others,” reflects Martinez-Granados. “I hope people who encounter my work will find a new way of understanding immigration or someone else’s lived experience.”