It has been three weeks since I watched Vox Lux. Whenever I think about how to approach writing about it, in my head I hear the voice of Bill Hader’s Saturday Night Live character, Stefon: “New York’s hottest club is VOX LUX. This place has everything: sequined unitards, mass shootings, creative neckwear, drugs, voiceover by Willem Dafoe, two characters played by the same actress.” Stefon, I believe, would have loved Vox Lux. It’s exactly the sort of over-the-top mess that also makes an excellent dance club. Everything is on the table; nothing is held back. It’s maximalist and then some. When it’s over, you feel a little dirty and you wonder, What did I just see?

Director Brady Corbet knows exactly how a good pop song works. So does Sia, who wrote all the songs for main character Celeste, played by a young Raffey Cassidy and then later by a very adult Natalie Portman. Pop songs are catchy; they have a hook that is usually, at its heart, sentimental. Early in the film, as a victim of a school shooting of the sort that originated in the late 1990s when the film’s first half is set, young Celeste sings a heartbreaking ballad that she wrote while convalescing in a hospital bed. The song catapults her into superstardom. We see her clumsily try out dance moves, acquire a handsy manager (a brilliantly seedy and aged Jude Law), while bands of velvet or scarves continually hide the scars of her gunshot spinal injury. As Celeste gains strength and fame, it’s easy to root for her. She’s quiet, she’s sensitive—maybe even a little naïve. More importantly, she has the goods.

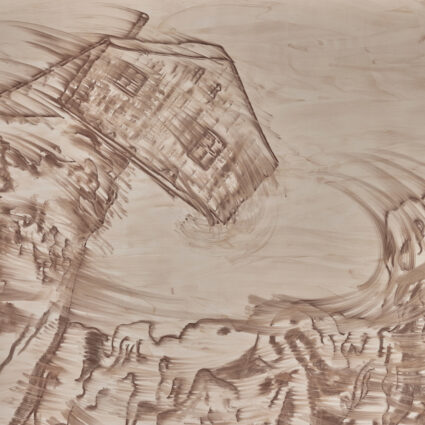

Cut to 2017, cue the synths and the lights and the production designers and the paparazzi, and that initial pop hook becomes a beast, a full-force spectacle that threatens to consume Celeste and everyone around her. Celeste is all grown up, and barely a glimpse of her former self (unless you count her teenage daughter) is recognizable. Watch as she surreptitiously guzzles white wine through a straw, then verbally abuses her waiter. 9/11 has come and gone, but Corbet’s intermittent shots of towering New York buildings and period footage of the Twin Towers that set the scene for Celeste’s arrival in Manhattan remind us that the backdrop of Vox Lux is an era of catastrophe and tectonic cultural shift.

When one is still trapped inside an era, events swirl in an undifferentiated array of phenomena. Trends lead nowhere.

I’ve encountered a few works of art in the past year or so that look back on the recent past and seem, at last, to be able to grapple with it as a historical moment. They seem to herald the arrival of a much-awaited critical distance—an ability to see patterns instead of chaos. When one is still trapped inside an era, events swirl in an undifferentiated array of phenomena. Trends lead nowhere. Paths overlap and double back and offer no clear way out, no venue for reflection, self or otherwise. Like Vox Lux, Ottessa Moshfegh’s novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation, set in the early months of 2001, finally pulls back the curtain a little. Both works feature unashamedly egotistical and reckless protagonists hellbent on self-destruction. Portman is not fun to watch, as we have come to expect from our pop stars. Yet she may be the pop icon we deserve. Unlike its maudlin mirror image, the newest iteration of A Star is Born, Vox Lux doesn’t pander to its audience with the pretense of a love story or a sympathetic lead with tinnitus and abandonment issues. It’s all spectacle, and Portman plays it to the hilt. By its final scene, it’s no longer possible to see Celeste the person, even as she flawlessly commands the stage. Yet her melody still has a hook. Revel in it.