Ogden Contemporary Arts’s second artist in residence Eric J. García invites us to scrutinize the principles upon which American history and identity are based in a dazzling and multifaceted artistic project.

OGDEN, UT—Ogden’s history as a railroad town sets it apart from the predominantly white settlements promulgated by Mormon pioneers, and continues to be one of the few Utah cities known for its ethnic diversity. It’s here that New Mexico-based artist Eric J. García has developed the multi-faceted project Aim High, the culmination of his tenure as the second artist-in-resident at Ogden Contemporary Arts.

The Albuquerque-born artist—a Southwest Contemporary New Mexico Artist to Know in 2022—is known for his multi-disciplinary practice, including printmaking, sculpture, installation, and mural projects, among others. His process utilizes satire and pop culture references, including science fiction and comic illustrations, to bridge parallels between history and the present. Notably, his work invites us to ruminate on the lexicon of colonialism, reappropriating terms like “alien” to demonstrate the hypocrisy of anglified dominance of American history.

His OCA project comes in two parts—an outdoor community mural on a wall of the historic Monarch building that houses the gallery, and Aim High, an exhibition within OCA that serves as the culmination of his residency.

García, who earned an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BFA with a minor in Chicano studies from the University of New Mexico, has designed mural projects for locations across the country, including in Chicago; Grand Rapids, Michigan; St. Paul, Minnesota, and his home state of New Mexico. Because he had only passed through Utah prior to his residency, he enjoyed the opportunity to spend an extended amount of time in the state and, in particular, Ogden, which he calls “a great city [and] a little cultural hub of artistic happenings.” As with many of his mural projects, he investigated the qualities unique to Ogden and quickly intuited the town’s difference from the majority-LDS population that surrounds the northern Utah city.

García notes that community came in many forms during his project. For one, he lauds OCA’s family-focused residency, which allowed him to bring his wife and son to experience the location he immersed himself in for two months. Of his investigation into the region, one thing perhaps above all else stood out to García—the environmental catastrophe of Utah’s drought and the shrinking Great Salt Lake.

“While I was here, I learned about the Northern Shoshone Nation trying to reclaim lost land and repopulate that land with native plants to revitalize lost systems, which will inevitably go back into the Great Salt Lake,” he tells Southwest Contemporary in a phone interview. “The Great Salt Lake became incorporated into the mural itself because I was struck by how big of a natural disaster it would be if the lake went away.”

García visited the lake and witnessed the recession of its shoreline, which, along with the region’s poor air quality, could spell disaster for the region. He fueled this realization into his community mural, which he made with the help of residents and groups, including the Ogden Youth Impact Program.

The mural features a young girl donning a white dress and face mask—she clutches a yellow bag of seed in one hand and a bright yellow umbrella in the other. The illustration style of this figure recalls the Morton Salt design. Behind her, horizontal rows of pink and white flow as smokestacks compose the upper register of the mural, coalescing out of refinery towers in the work’s right corner. This industrial scene stands in opposition to the reeds and marshland on the other side of the figure, as if to warn us of the impending dangers that await us if we fail to heed the environmental impacts of manufacturing. The mural’s bold colors and geometric design are visually striking, its message even more so as each section invites careful contemplation and reflection.

Interactivity is at the core of García’s artistic process, which he hopes will ignite curiosity about the times in which we live.

“It’s a huge responsibility to create political art in times of dire straits, but it’s important to use all the instruments and tools we can to talk about things that are important and impacting our lives,” he says. “Art is one of those tools or weapons to poke at the blatant unlawfulness, the injustices, the important issues of our time.”

Inside OCA, García has crafted engaging art projects that, through their interactivity, aim to invite participants to reexamine predominant historical narratives.

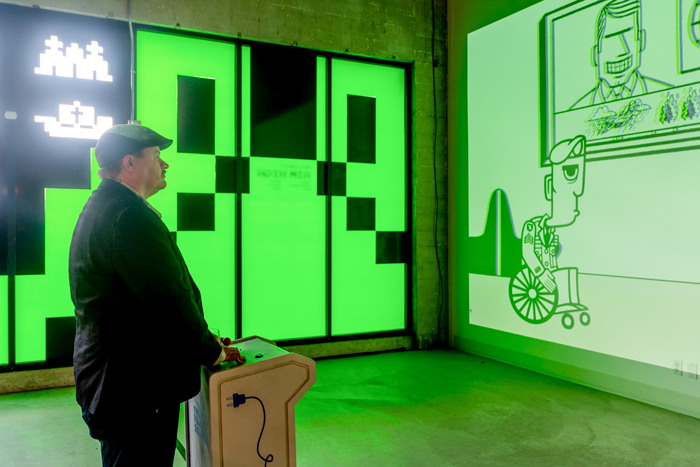

In Discharged (2023), participants jump into the life of a military veteran returning from war. The game, which has been in development for three years with García’s collaborators at the Plug-In Studio, is in reaction to first-person active-shooter video games that glorify warfare. The game explores the difficulties of a disabled veteran who navigates a complex and often hostile landscape of bureaucratic and psychological burdens.

The other interactive video project bears the retro markers of the first generation of arcade-style gameplay, its design mimicking the classic Space Invaders with extraterrestrial icons replaced by symbols of colonialism such as Spanish conquistadors. In the game, which García created with Rafael Fajardo, one becomes an Indigenous person shooting the invaders, a play on the idiocy of the American lexicon of “alien” immigrants entering the ancestral homelands from which they were originally expelled by colonial invaders.

In between the interactive projects are ink illustrations that reimagine historical episodes of colonialism, erasure, and genocide in science fiction backdrops. Of note here is the illustration Game Over (2023), depicted in the highly pixelized style of early arcade games, which shows an explosion and dust clouds. The letters “NM” and “1945” appear at the top of the image, referencing New Mexico’s history of nuclear testing. The ambiguity is tantalizing, as the detonation is pictured as a vertical beam projecting downward, like an alien spacecraft. The words “GAME OVER” appear at the bottom of the image in a double entendre of the culmination of this game of life.

OCA, with its first two selections in their artist-in-residency program—Ya La’ford, who presented Survey: The West, was the first—has excelled at choosing artists who have a national reputation and who have a keen desire to understand the politics of place. For both La’ford and García, situating themselves within the community is an integral part of their artmaking processes, a from-the-ground-up methodology that refrains from imposing a certain artistic vision upon the community. Instead, each artist hopes to share a certain aesthetic and intellectual vision for artmaking while leaving open critical space for reflection and alteration of that artistic process. Each seems to have learned something more, not just about Utah, but the American West.