Christian Ramírez’s scope is technically local at Phoenix Art Museum, but the assistant curator channels years of Southwest connections from Tucson to El Paso.

Pinned gallery announcements and newspaper clippings about contemporary artists fill the corkboard behind Christian Ramírez’s desk at Phoenix Art Museum. Atop a row of file cabinets sit several binders, a living archive of curiosity and history worth preserving.

“Being an artist is so brave, and you are so vulnerable,” Ramírez says. “You just have to have really tough skin to be able to keep making what you want to make, despite what other people might think or say.” As an assistant curator at PAM since 2023, Ramírez has defined the museum’s first-ever role focused on “local artists and community-art initiatives.” It’s her job to hold artists and their stories in ways the larger world often doesn’t.

Through her childhood, Ramírez traveled routinely between Tucson and her hometown of Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico. She was visiting her grandparents, who had raised her during her earliest years, before she moved to the United States to reunite with her mother, who had immigrated ahead of her.

During the four-hour drive, Ramírez would watch the Sonoran Desert pass by her window. It was a landscape that would later become a focal point, shaping her curiosity about how diasporas and art intersect.

After graduating from the University of Arizona with a BFA in fine arts photography, she realized—along with some of her friends—that Tucson lacked opportunities for them as emerging artists.

They did something about it in 2016, when Ramírez, Andrew Shuta, Alex Von Bergen, and Maya Hawk cofounded Everybody, a gallery that started as a warehouse project with storefront pop-ups and parking lot shows.

“Back in those days, we could afford it,” Ramírez laughed. “It was like $300 a month for rent so between the three of us, it was totally doable.”

Taking with her the essence of Everybody, Ramírez made her way to Phoenix to accept the role of public programs manager at Phoenix Art Museum. After the pandemic paused some of the programming, she moved to San Antonio, Texas, to continue her journey as the exhibitions and residency manager at Artpace where she reconnected with Rigoberto Luna, co-founder of Presa House Gallery.

Since they first met in Tucson, the pair has cultivated a friendship built on the mutual understanding that it’s impossible to separate themselves from their work. Leaning into who they are and where they come from is the only way to properly represent diverse artists.

“She’s a hard worker,” Luna said. “She really cares. I think the care is the big thing about the work that she does, and I mean, that’s really what curating is.”

We’re going to have someone there who’s going to have our back, and to have that in these kinds of spaces has been long overdue.

Though Ramírez later returned to Phoenix, she and Luna remained connected through a shared mission: to collaborate with underrepresented and emerging artists.

“Our careers have grown similarly,” Luna said. “For her, being in Phoenix, demographically, there’s a lot not being seen and a lot not being said, and I think that there’s power in the position that Christian has.”

Reflecting on her time in San Antonio, Ramírez recalls everyday emblems of Tejano pride—Texas-shaped waffle irons, bumper stickers, tattoos—that permeated the way community members interacted with one another.

“It’s kind of incredible that they ride so hard for each other,” she said. “Being there made me think ‘oh man, I wish there was something like that in Arizona.’”

Arizona’s art community was apparently longing for that, too.

One of Ramírez’s recent collaborators at PAM is artist Gloria Martinez-Granados, a former DACA recipient who makes work inspired by her upbringing as an immigrant. She often welcomes curators into her space and says that working with Ramírez has been a unique experience.

“Her background, because of who she is, is such an important element in our collaboration,” Martinez-Granados said. “To be able to bring me into these spaces that traditionally have been spaces where people of color don’t really find themselves in.”

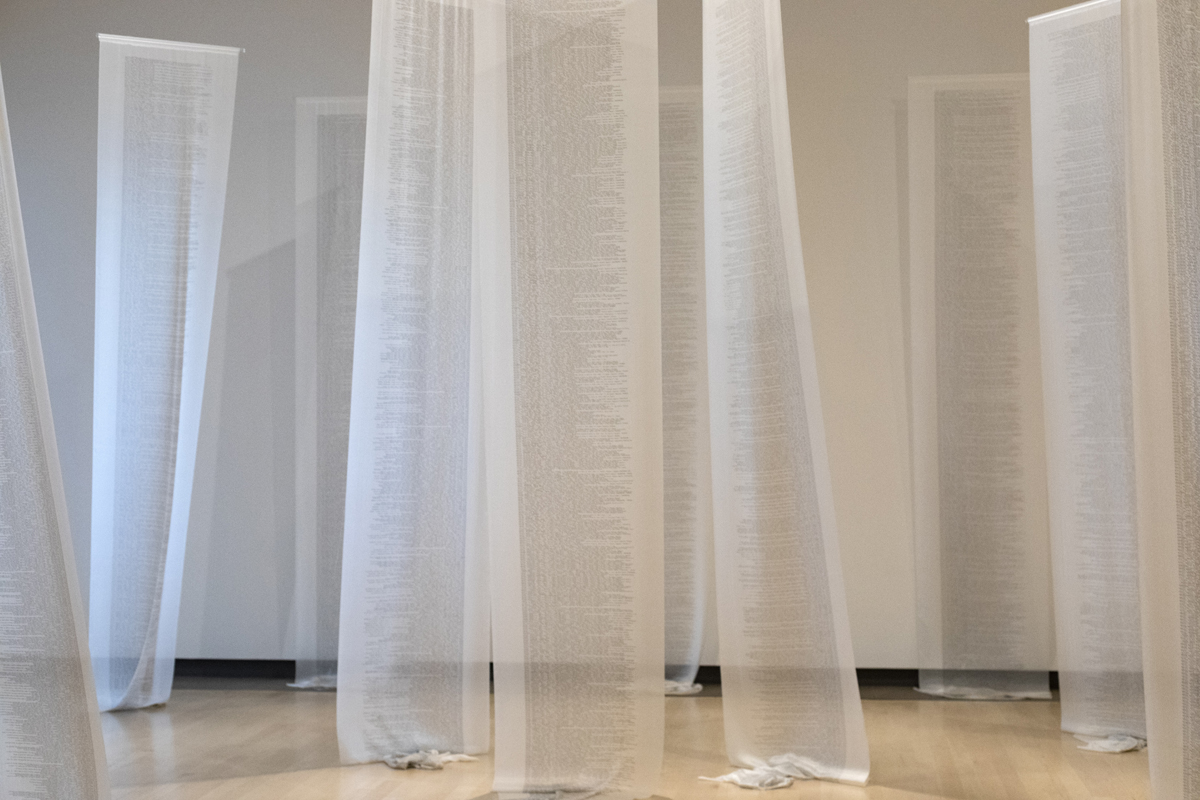

In 2023, Ramírez selected Martinez-Granados’s fiber artwork Braceros: Can 48,900 stitches hold history? for the group exhibition Son de Allá y Son de Acá. As part of the curatorial team, Luna learned about Martinez-Granados’s work, and two years later, invited her to be a part of Ya Hecho: Readymade in the Borderlands, an exhibition at the Tucson Museum of Art.

Luna and Ramírez’s respective efforts say a lot about the need to make room for Latino and immigrant artists. Because both communities are historically underrepresented in contemporary art, the connection between a curator and the artist they select is often personal.

Martinez-Granados views Ramírez’s presence as a reminder that “we’re going to have someone there who’s going to have our back, and to have that in these kinds of spaces has been long overdue.”

From Tucson, San Antonio, and Phoenix, Ramírez has helped transform how an art space functions in the Southwest, uplifting local artists who inspire dialogue about issues impacting them and their communities.

“Those artists are a part of Arizona’s history,” Ramírez said. “Their work does all these different things that touch on the environment, immigration, migration—there’s a huge range to what their work is about and that’s accurate in this moment. So, I hope people see themselves reflected in it because it’s made by people that are from here, too.”