The process-oriented work of Brie Ruais—a Santa Fe-based artist who makes conceptual and gestural performance art for a new generation—recenters artmaking in the body.

“Sometimes the activity involve[d] making something, and sometimes the activity [was] the piece.” —Bruce Nauman

It’s hard to describe the feeling of walking through an exhibition of Brie Ruais’s work. On the one hand, the Santa Fe-based artist’s wide-ranging practice is guided by strict parameters, rendering her pieces elegantly straightforward. Almost all of her ceramic sculptures, for instance, are produced using the same amount of clay—130 pounds, to be exact, the equivalent of Ruais’s body weight—without employing any tool but the artist’s body. Even in her site-specific video work, Ruais’s mise en scène is always as minimalist as possible, so the eye focuses on the artist, the material she works with, and nothing else. Though every installation is entirely unique, Ruais’s ritualistically tight scripts simplify things.

On the other hand, the consistency of Ruais’s practice has opened possibilities that a single experiment in clay never could. In her twelve years of dedication to working with her body weight in clay—using only her hands, feet, arms, and legs to coax the material into being—Ruais has invigorated both body-based conceptual art and gestural performance art for a new generation.

While many have categorized her practice as closely aligned with site-specific, process-oriented precedents of the ’60s and ’70s, like Michelle Stuart, Judy Chicago, Ana Mendieta, and Richard Long, it’s clear to me that Ruais’s commitment to her parameters has allowed her work to flourish in its own direction. The result is pure poetry. Los Angeles Times critic Sharon Mizota aptly described Ruais’s sculptures as “a choreographed dance in clay.”

“There’s a lot that comes about when you work with the same material, in the same weight, in the same way, over so much time,” Ruais tells me. “In setting these strict parameters for myself and returning to them, over and over, I’ve found that they allow completely unpredictable things to unfold within them.”

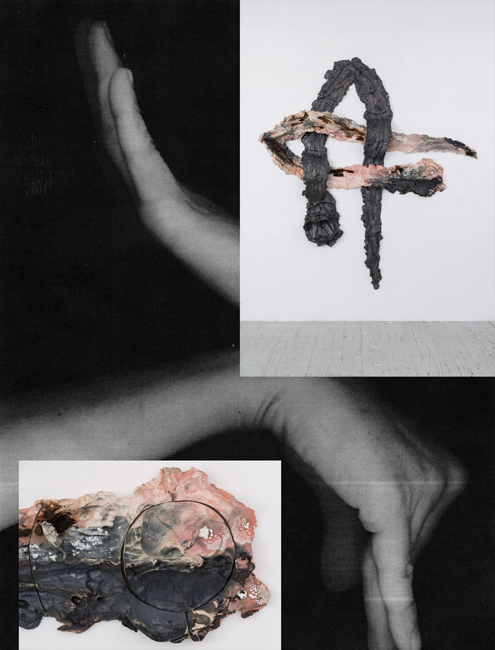

Despite her strict parameters, Ruais’s diverse collection of work is far from constrained. Because her practice is oriented around her process, the name for each sculpture is informed by the experience she encountered throughout its creation, such that, even though many of her recent sculptures were produced in the same manner—with Ruais kneeling on the ground and spreading the clay outward from the center in all directions to form circular, flower-like sculptures—every iteration is entirely individual.

For instance, her most recent exhibition at Night Gallery in Los Angeles, Daughter, You Seem Foreign to Me, is the result of a connection Ruais drew between her mother’s battle with dementia and the image of the moon.

“The name of the show came from something [my mother] said to me, which was, ‘You seem so foreign to me,’” Ruais explains. “I remember thinking, ‘How can that be? I came from your body. We’ve known each other for forty years, and now we’re suddenly strangers?’”

The exhibition acted as an illuminating study of the way light glides across the moon’s surface, with each fragmented and glimmering wall-based installation representing a subsequent lunar phase. For Ruais, the simultaneous closeness and distance that we experience with the moon helped her make sense of her feelings about her mother. “We’ll never touch it,” she continues. “And yet it touches us. These dualities take on different stories and then make their way into the work.”

Over the years, several stories have informed several series of Ruais’s sculptures. A graduate of both the New York University Steinhardt School and the School of the Arts at Columbia University, where she studied with Jon Kessler, Ruais’s earliest work is defined by rigorous experimentation.

“My work began with an interest in choreography and movement and expression and has turned into a space of ritual,” Ruais explains. “I say that because, while I’m working, I am always in conversation—with the material, with my body. I think what happens in ritual is you become tuned into parts of your mind or body that you can’t as easily tap into during normal experiences. Very often, what happens when I’m working is that the self-scrutinizing part of my mind turns off, allowing me to be absorbed in the moment of making the work.”

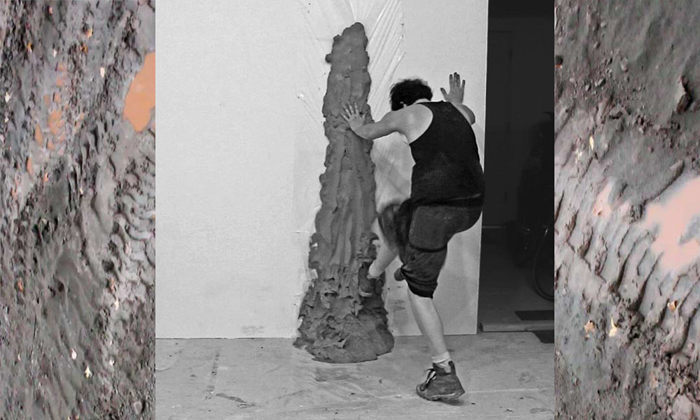

A performance still from 2012, for instance—a year after she completed her MFA—captures the artist bracing herself on a wall with one leg extended as she pounds a mound of clay with her boot. With the mound thickest near the ground and narrower as it climbs the wall, the end result looks like a kind of lumpy spire.

To complete Push Ahead, Turn 180 degrees, Repeat (132lbs., Yellow and Violet) (2014), Ruais shifted from working with clay on a wall to wrestling with it on the ground, where she knelt and pivoted on the same point and pushed the clay in opposite directions. Smooth in sections and jagged in others, Push Ahead seems one step closer to her later works, as it retains the memory of the artist kneeling in its center, where the clay is worn down to almost nothing.

The more time she committed to these parameters, it seems, the more of her body the work demanded. Just a few years into her practice, Ruais began employing her forearms, elbows, knees, fingers, and toes instead of using one hand or foot to mold and shape the clay. In other words, as the experiment expanded in time, so did her absorption into it.

“It’s an incredibly physical task, working your body weight in clay,” Ruais says. “I’m curious to see what happens as I age and my ability changes. Even though my work has already changed so much, it all comes from the same starting point. Each work is a new take on the same basic form.”

When I ask Ruais if the repetition of that ritual, that return each day to the same measure of the same materials, ever felt “repetitive,” she explains, “Because this one gesture or movement has been repeated so many times, my mind completely turns off, which allows me to be in the moment—to be in my body.”

“I used to be afraid to push the limits of the material because it often wouldn’t stay together,” Ruais says about her years-long relationship with clay. “In hindsight, I think that some of my most exciting discoveries have come about when I take a risk and push a material past its limits and then figure out how to troubleshoot that.”

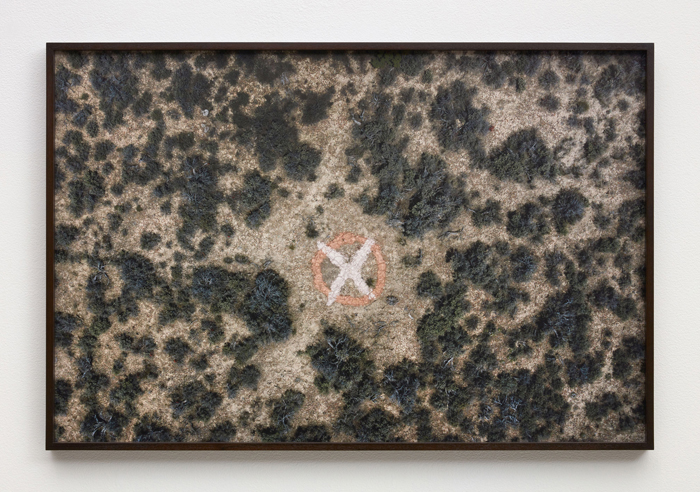

The titles of one of Ruais’s works displayed in her 2016 exhibition at Young World in Detroit—How to Wander (Push double your body weight in clay in a spiral, create hiccups along the way, then arbitrarily strike out in one direction.) 260lbs—captures another experiment within the same parameters. This time, instead of pushing the material outward from a single location, Ruais followed a path, moving her body with the work as it snaked across the floor. She would return to this technique several times over the next few years, developing overlapping and interwoven sculptures including With Their Inners Woven (2x 130lbs) (2017), an intimate dance between a dark and light thread of clay, as well as Interweaving the Landscape (four times 130lbs) (2018), an ambitious iteration that quadrupled her typical volume of material to form a mesmerizingly complex system of crisscrossing paths.

Observing her work unfold across time reminds me of the way Willem de Kooning wrote about his work in 1948: “I paint this way because I can keep putting more and more things into it—drama, anger, pain, love—through your eyes, it again becomes an emotion or an idea.” In this same vein, Ruais describes how she understands her relationship to her work and her work’s effect on her audiences.

“In my personal experience, art is something that passes through an artist and transforms as it’s filtered through their personal experience before it goes back out into the world. I am always beginning and ending in my own experience, but I can count on other people relating to that journey because art comes from a well of experience that everyone has a relationship to.”

Though her devotion to her practice has already succeeded illustriously, Brie Ruais is far from finished. If anything, she has more momentum now than ever.