Ben Aleck’s exhibition at the Nevada Museum of Art looks at thirty years of work by the artist and Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe member who has witnessed key Native American political moments.

The Art of Ben Aleck, on view through January 7, 2024, at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, surveys Aleck’s engagement as an artist, educator, and enrolled member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe through thirty years of paintings, drawings, and mixed media collages that integrate landscape, story, and Native pictorial traditions.

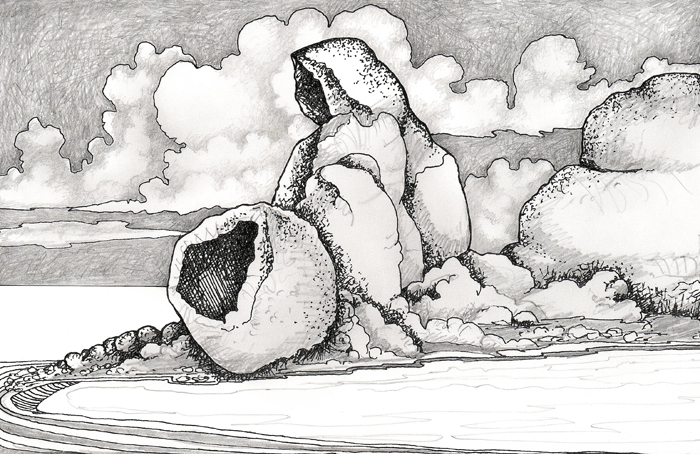

Born in 1949 in what is now the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, Aleck describes how a given work begins with a “place or landscape,” after which he considers its associated story. “Following that,” he says, “I add geometric designs inspired by traditional Paiute Native American artists after seeing their works at powwows, craft shows, or in museums.”

Politics and history are ever-present as a result. His artworks also incorporate Aleck’s experiences as a young art student who lost his brother in the Vietnam War, his involvement in the American Indian Movement, and his adventures living in the Bay Area, South Dakota, and Arizona before he eventually returned to the Great Basin. Perhaps not surprisingly, Aleck employs the picture plane as a tool for memory and teaching, recalling marginalized Native histories too easily pushed to the periphery of common knowledge.

In his painted portrait Red Shirt (1972), the Oglala Lakota chief sits in profile in a European-styled vest and shirt. He wears a buffalo bone necklace, one rope of long hair wrapped in a purple cloth with a smaller braid lying beneath it, and a red-painted face. Based on a Charles M. Bell photograph taken at the urging of Bell’s patron and land surveyor Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, Aleck disrupts the settler-driven frame to prioritize Red Shirt’s contribution to Native history.

“My primary objective was to counteract the derogatory, stereotypical view of Native Americans as ‘Redskins,’” Aleck says about the work he painted during the American Indian Movement. “I wanted to honor this important Oglala Lakota chief, warrior, and statesman… who fought with Crazy Horse in the Great Sioux War of 1876 and the Ghost Dance Movement.”

Aleck’s image-making impacts collective memory and legacy, transforms historical views, and captures multiple temporal frames in a single work. For instance, Aleck drew Chief Gall (1969/70) on a piece of paper that the artist found while visiting Alcatraz during the AIM occupation, which took place for nineteen months from 1969 to 1971. Visceral marks place the image of Gall, a crucial military leader of the Hunkpapa Lakota in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, on an artifact of historic protest, its surface torn and creased in places as a physical record of the time.

“The day I spent on Alcatraz during the AIM occupation, I was down in a maintenance basement with rolled-up floor plans,” Aleck explains. “When I later opened up the roll, I discovered the paper that I thought I would use to commemorate the AIM occupation—a proud moment in history when Native Americans took a stand.”

Spending time with his work, one cannot help but sense Aleck’s holistic approach. As he puts it, “My hope is that my work will inspire younger people to creatively express themselves. In my community that experiences a high degree of poverty, doing artwork is a way to transport a young person into a better place and a brighter future.”