JC Gonzo’s photographs of New Mexico cemeteries place viewers in a symbiotic relationship with the land, community, and history.

SANTA FE—Morbid as it may be, there’s no denying the melancholic allure of a graveyard, especially an abandoned one. There are many reasons for the appeal—curiosity, fascination with the taboo, the desire to be alone.

It seems the main attraction of an empty graveyard, strangely enough, is that it shows signs of life.

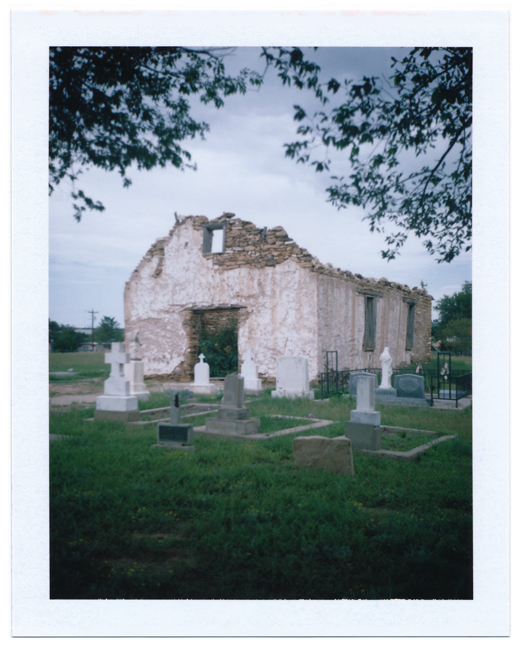

This odd contradiction is amplified in a desert landscape. Visitors to New Mexico are usually in awe of two sequentially occurring phenomena: that the territory appears to be “empty” and “untouched” even though this land has been continuously occupied by human civilizations for thousands of years. The evidence of life where it shouldn’t be, the pure resilience, seems to be part of the attraction.

For New Mexico artist JC Gonzo, the fascination with cemeteries and the corresponding Southwestern geography, anthropology, and history is ever-present and receives ample attention in his photo series A New Mexican Burial. The place-based work of Gonzo, a multimedia artist who primarily works in photography, cinema, and writing, also reflects his distinctive praxis that he calls “meta-ecological research.”

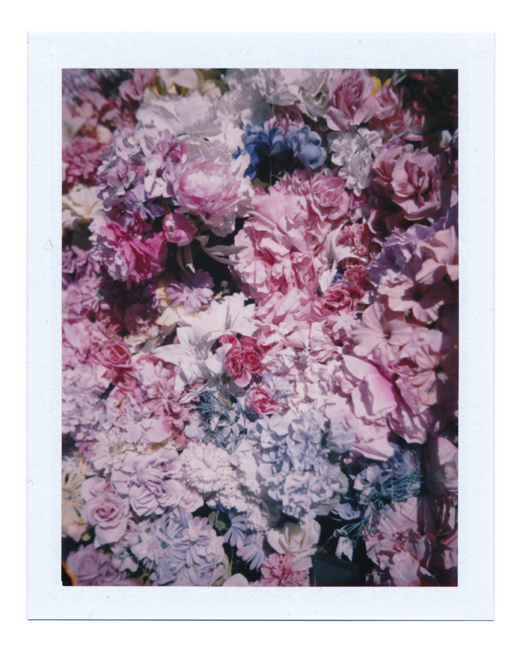

This research method informs his image-making by adding more context to the sites he photographs. The process consists of combing through several types of research texts (geological surveys, archaeological studies, botanical texts) in search of “poetic flourishes” that appear amid the heavy technical writing. Gonzo’s images reflect this behind-the-scenes research by foregrounding certain subtle details as the subject matter, such as dried cholla placed on memorials instead of flowers—a nod to the desert landscape surrounding the cemeteries in his Burial series. In addition to reading scientific texts on the Southwestern United States, he also looked through New Mexico Genealogical Society burial records, which influenced the series.

For Gonzo, this kind of research, and what results from it, goes beyond documentation. It also adds an aesthetic layer to historic and analytical information, and analog photography achieves something similar for the artist. Between the nostalgic look of Polaroids to the natural vignettes that tend to frame his vintage camera images, the medium and subject matter of Gonzo’s Burial series align in their anachronistic qualities.

“The crispness of a digital photo is purely documentarian,” says Gonzo, “and my photos are not trying to be perfect documents.” The reason he works in a range of analog techniques (including instant film, 35 mm, and 120 format) is to capture a feeling associated with the site and a moment in time.

The photographs of burial grounds and monuments are less about preserving the way a cemetery looks, and more about giving a feeling to the beautiful scene of life and death. It is sometimes difficult to tell whether A New Mexican Burial photo depicts an abandoned cemetery, or simply a space that has had little human intervention on the surrounding environment. In other words, not every image of tombstones and monuments, which can jut out from the dirt or might be cloaked by shrubs, means the graveyard is abandoned.

As Gonzo and I finished our conversation, we discussed the current state of cemeteries across the country, and the differences between heavily manicured graveyards and those on the edge of disappearance. Cemeteries can be seen as a document or record of a society and its culture. Oftentimes, the degree to which a cemetery is cared for is a good indicator of how much the surrounding community can invest in its history and change its present. One of the (in Gonzo’s words) “abandoned but beloved” graveyards featured in A New Mexican Burial is actually on the National Register of Historic Places.

This not only raises questions about our collective investment in our history, but also our future. Although a registered historic site is protected from demolition or redevelopment, this is the bare minimum of care. For many individuals, however, the idea of maintaining a cemetery plot is a daunting task requiring time and money; the loneliness of graveyards is also alienating to some.

But an interesting phenomenon occurred when Gonzo shared his Burial series on social media: strangers requested the artist to locate long-lost relatives known to be interred somewhere in the graveyards he was photographing. It was then that Gonzo’s practice and meta-ecological research method became fully realized as he was not only documenting these sites, but also bridging a gap between what is now and all that has come before.

“Being asked directly by family members was really neat,” says Gonzo. “The entry point is more accessible… to enter into the conversation through a more philosophical or aesthetic approach.”

The opening reception for JC Gonzo: A New Mexican Burial takes place from 6 to 9 pm Friday, October 7, 2022, at No Name Cinema, 2013 Pinon Street in Santa Fe. The exhibition is scheduled to continue through December 2022.