Alex Branch, a Denver-based interdisciplinary artist, ponders the life-death metaphors embedded in everyday objects, the mysterious lives of flora and fauna, and the aural experiences that inspire her art.

If you mine the Internet for information about the interdisciplinary artist Alex Branch, you’ll learn that she grew up on an island off the coast of Washington, collecting Earth-worn objects washed to shore, pondering the odysseys they mutely contain. As we sat in her studio in the Evans School (in landlocked, water-scarce Denver), I brought up my knowledge of her poetic biography and geographical migrations. From Seattle to Chicago and New York, and artist residencies in Greece, Florida, Missouri, Nebraska, and New Mexico, Branch set an anchor near family in Denver two years ago, finding herself among a supportive art community.

As I considered Branch’s works-in-progress in her studio, I shared her curiosity about the metaphors enveloped in everyday objects, like messages inside ocean-dispatched bottles. Branch gestured to her water bottle on her desk, telling me that even newly manufactured gadgets hold secret narratives about their production. Contemplating the independent, non-ontological lives objects lead, we admired their fusion of organic and synthetic materials, the animal and mechanical labor involved in their development, and their unpredictable transformations with exposure to various physical and social environments.

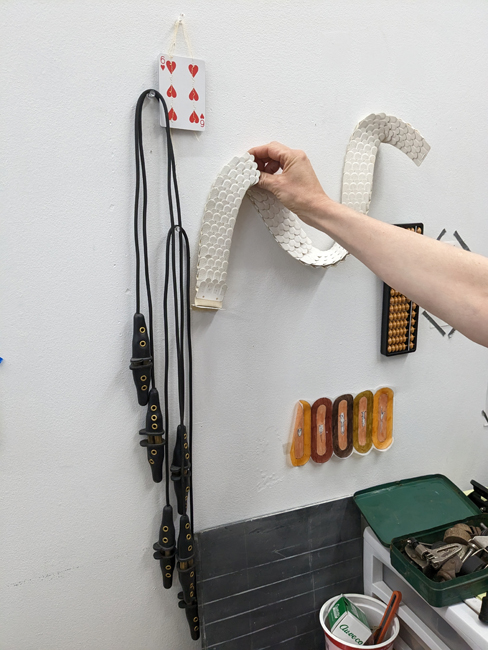

Inspired by her immediate habitat, Branch rarely travels far for installation materials, upcycling used and found items such as debris from alongside rivers and train tracks, free pianos listed on Craigslist, and uprooted trees from construction sites. Moreover, Branch conceives her projects while witnessing how people continuously modify their environments.

Discussing the uniquely human compulsion to render “large-scale fabrications,” such as amusement parks and art exhibitions, Branch and I found ourselves dwarfed by an ornate antique chair balanced on long-handled shovels. Indeed, her own recent, smaller-scale fabrications highlight her fascination with items paradoxically embodying life and death. In the case of the shovel, it both inters corpses and cultivates vegetation. Nearby, another shovel with an undulating, serpentine handle lay in wait on the ground.

This ouroboric preoccupation with the life-death cycle also recalls her piece, Tumbling Tumbleweed (2020), which showcases the Russian thistle on a treadmill, somersaulting its way to nowhere. Elsewhere, Branch comments on the macabre allure of this restless shrub: “The plant is dead, but in its death it’s spreading seeds and creating new life.”

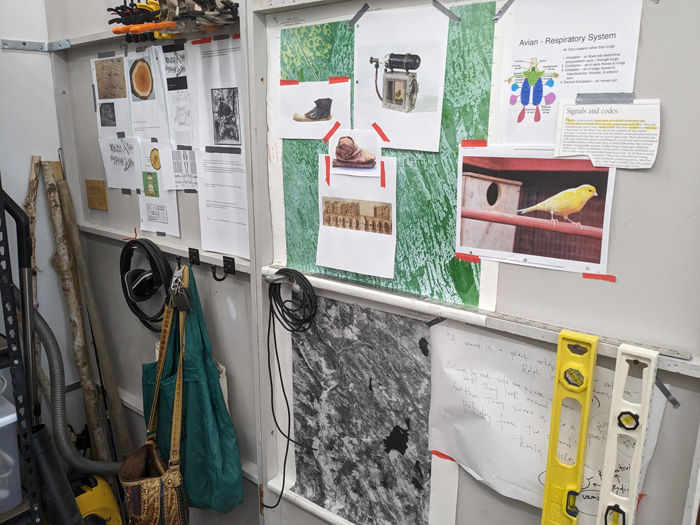

Additionally, Ground Cover (2023), Branch’s solo exhibition at Denver’s Understudy this past April, featured dead plants. Seeking an answer to a self-imposed question—“Can nature be simulated?”—Branch presented dried stalks of wheat wavering on a conveyer belt, reproducing the sound of their windblown rustling. Neighboring this fragmented pasture, a trunk of beetle-kill wood, with three small embedded monitors, played video images of the inside of a tree.

Noticing a garbage sack filled with Ground Cover grass tucked into a corner of her studio, I asked Branch if she recycles materials from past exhibitions. Again betraying a captivation with death, Branch meditated on the carpentry-joinery term “carcass,” the framework of a cabinet or dresser into which drawers are fitted. Planning to use a drawer-less carcass of a bureau, Branch will invite you to look into its body at golden turf driven by a motor and V-belt.

The monitorless beetle-kill trunk also lay dormant on her studio floor. “As the tree dried, it began to compress the monitors so I had to remove them,” Branch explains. This occurrence inspired another inchoate project in which Branch will purposefully distort malleable items in naturally constricting wood.

A woodworker herself, Branch has corresponded with a boat builder in Maine and toured the workshops of violin makers, conducting research for her experimental sculptures. Inside a boat, quietly listening to its “resonance,” she first yearned to make her own seaworthy musical vessel. Soon after, she manufactured two distinct boat and musical instrument hybrids, each dependent on human bodies to activate their sound, and which have been played by select musicians.

Planning a third boat for her fleet, Branch envisions one percussing in tempo with the movement of the water beneath it. This boat, and other upcoming pieces, will downplay human interaction, forcing us to notice the abundant, unintentional creativity in a non-human-centered world.

To this end, Branch also wants us to consider the pests we cohabitate with. While living in a rodent-infested apartment in Brooklyn, Branch imagined setting up zoetropes in her building’s basement, providing creative recreation for her furry housemates. However, her friends talked her out of this project, insisting that only “bored, captive mice run on wheels.”

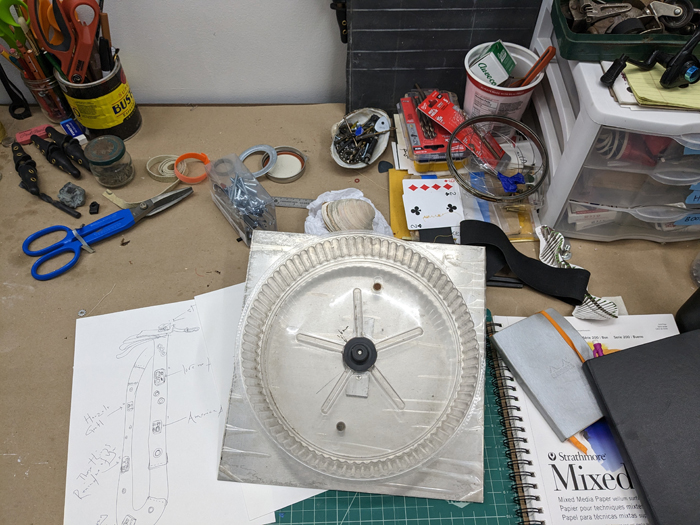

Later, Branch discovered the work of Johanna Meijer, a Dutch scientist who studies animals and play. Meijer confirmed that mice do run on wheels placed for them in the wild and gave Branch a prototype when Branch visited with her in the Netherlands. As Branch showed it to me, it reminded me of a plastic cake cover.

Now Branch is contemplating using the energy mice generate on wheels to project a film on the outside of a mice-inhabited building. Thus, Branch wants to turn our experience of a space assumedly by and for humans “inside out.” Since the mice will exercise on their own time, viewers will have to align themselves with the rodents’ nocturnal clock to appreciate the work.

Unsurprisingly, Branch’s aural sensitivities intersect with her fondness for the animal kingdom. When I asked Branch about her earliest memory of sound, we returned to her recollections of childhood in the Pacific Northwest and the colloquially termed “peepers”—the frogs whose croaking symphonies annually announce the onset of spring.

By the end of my studio visit with Branch, I felt like Alice in Wonderland, shrunk to fit inside my own glass bottle and swept away by the torrent of a meandering conversation. Traversing through themes of the natural, synthetic, and surreal aspects of our reality (shared with a multitude of entities we cannot fully control or communicate with) Branch ignited my wonder about a conscious world independent of us.

Branch is currently part of the group exhibition Tender Machines at Denver’s Union Hall. The show is on display through July 1, 2023.