He was a Marlboro Man from Moab who sold his art to celebrities in Los Angeles, before dying of AIDS. Why did no one have any record of his art?

This article is part of our OBSESSION series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 12.

I would’ve lost myself in Hollywood’s labyrinthine hills without Ernie, who led me back down to the billboard where the Marlboro Man used to watch over Sunset Boulevard.

He drove a BMW that looked new and electric; I followed close behind in a 1988 Nissan pickup that had somehow made it down from Moab, Utah. We parked outside a pink taco shop and he joined me on the tailgate.

“That one there,” Ernie said, pointing to an oversized billboard across standstill traffic. “If Dan was a Marlboro Man, he would’ve been up there. They all were.”

But he wasn’t there anymore. Now the ad was for Apple’s “visual intelligence”—an image of an iPhone scanned a product and asked “real or replica?”

Ernie and I said goodbye. I lingered for a while, looking at the billboard. Real or replica?

I had come to Los Angeles hunting for the lost work of Dan Buckingham—a Moab local who died of AIDS after a decade of selling his work to collectors and celebrities in LA. And three weeks in, after exhausting every conceivable resource, I had found no trace of Dan in the City of Angels.

As dusk creeped up, the reality of my treasure hunt dawned: his work might be gone with him. Hope I didn’t know I was running on suddenly drained out from me, onto that little parking lot off Sunset.

Did his artwork even exist? Had he ever towered over Sunset smoking a cigarette? And why had I given so much of myself to finding him? Real or replica?

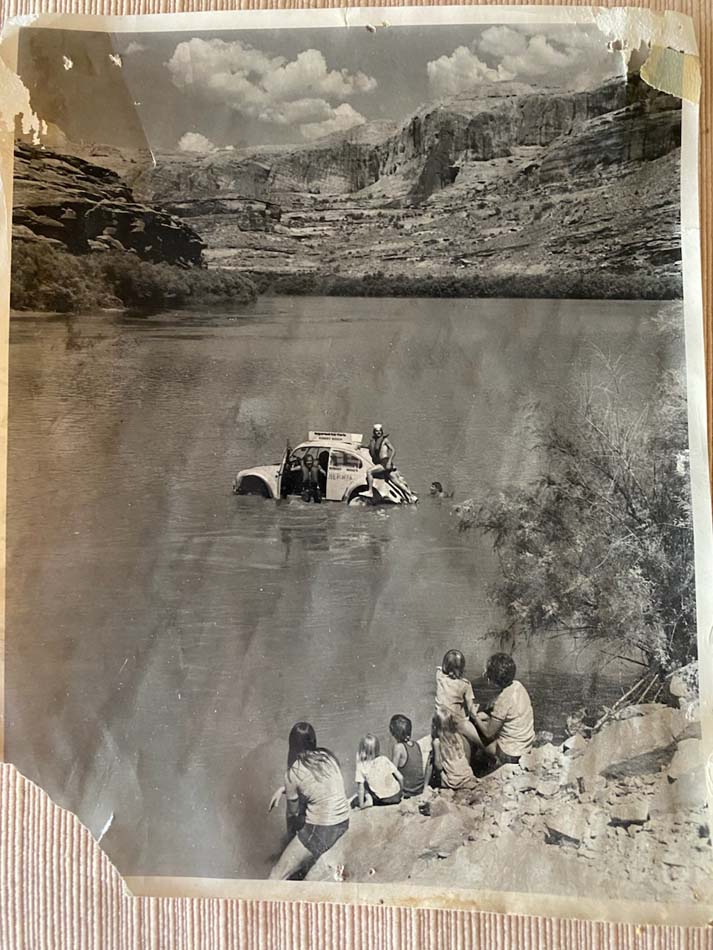

It was a hunt that began in Moab, when I met Dan’s brother. I had biked up to Moab’s new cemetery all sweaty and determined, as I was on the job, reporting for a local paper on some freshly installed columbariums that would change how Moab buried its dead. Robert Buckingham, the county sexton, greeted me like an old pal at the cemetery office. What should’ve been a quick interview lasted hours, followed by a friendship chock full of his Wild West stories—outlaw uncles, Moab legends, and a trailerpark childhood.

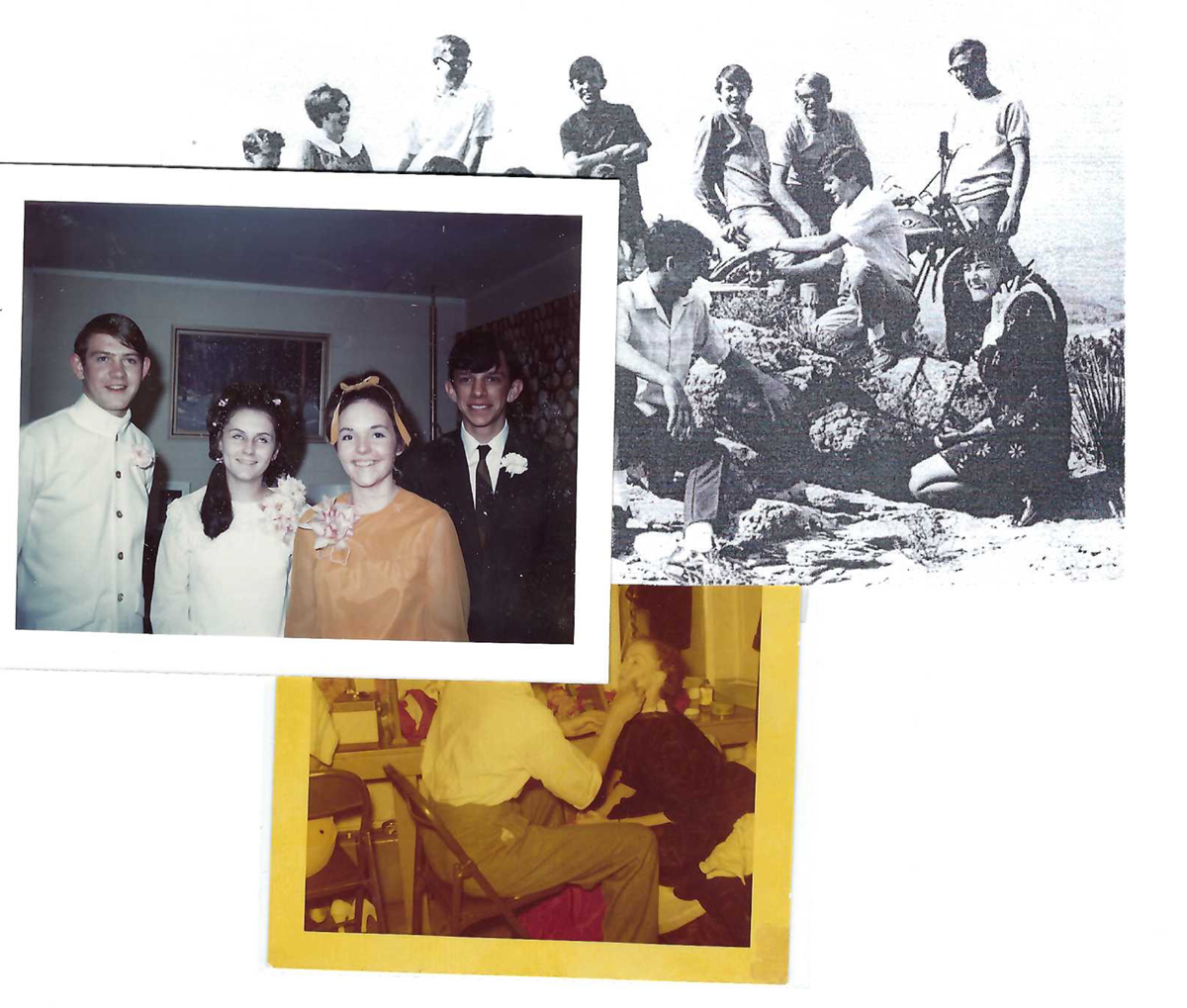

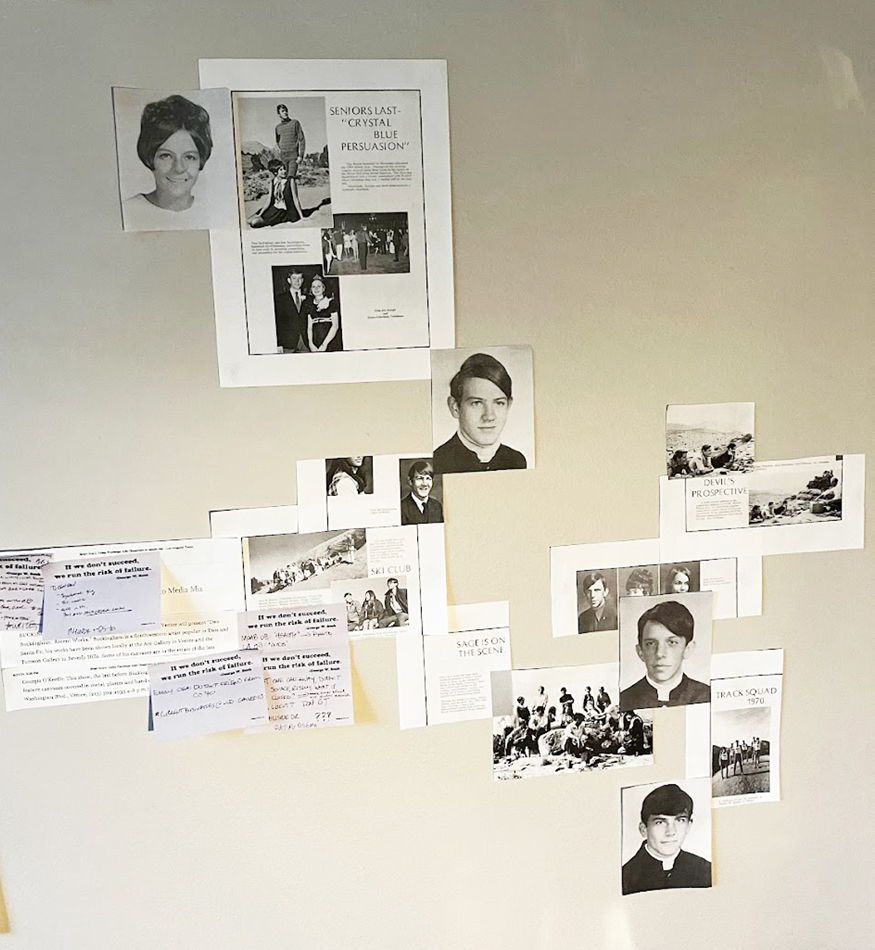

Robert—one of four boys who bounced around the Intermountain West with a roustabout father—landed in Moab as a junior high schooler in 1969, when his mother finally refused to keep relocating. Life in Moab was good.

On their way out for a drive-in movie, Robert and his older brother Dan would’ve greeted their father’s poker guests, including a heavily bearded man they called Uncle Ed, who they didn’t know had recently published a commercially unsuccessful novel called Desert Solitaire.

As dusk creeped up, the reality of my treasure hunt dawned: his work might be gone with him.

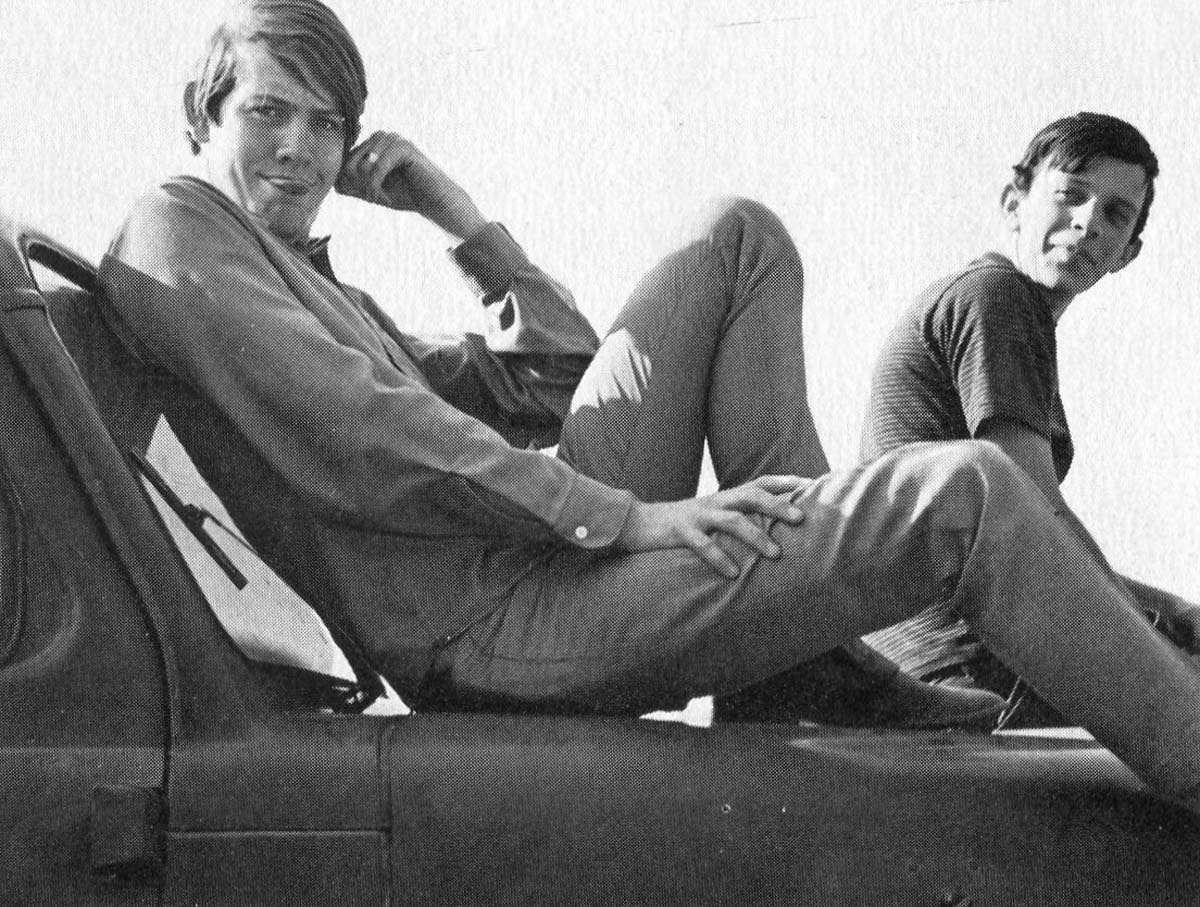

Robert, too young for the movies, would’ve snuck in stuffed in the trunk of Dan’s Chevy Bel-Air while Dan and his friends enjoyed the fresh air. Dan, while heavily involved in school affairs, kept his circle tight. His first girlfriend, Jane, remembered the boy she graduated with in 1970 as a great dancer who was well dressed and good humored.

She also remembered her last encounter with Dan in 1989—when she spotted Jack Buckingham’s hatchback at a gas pump. She hadn’t seen Jack, the oldest of the four who would eventually pass away from exposure to poison in Vietnam, and wanted to ask him about Dan, but her question answered itself when she approached the vehicle’s rear and saw Dan laying down in the back.

It was his turn in the trunk. Skeletal frame coiled like a fetus, and eyes lost on nothing, he didn’t even move to look up at her. Jane saw the tall, handsome dancer, her first love, who had spent nearly two decades in Los Angeles, dying of AIDS.

After graduating high school, Dan became a Catholic and married a woman who quickly divorced him. After that, Dan moved back in with his parents.

“My mother kicked him out in 1972 after she opened a letter from his best friend, who turned out to be his lover,” Robert says. He followed Dan to Salt Lake City for college, and Dan eventually settled in LA, where he earned the nickname “Buck.”

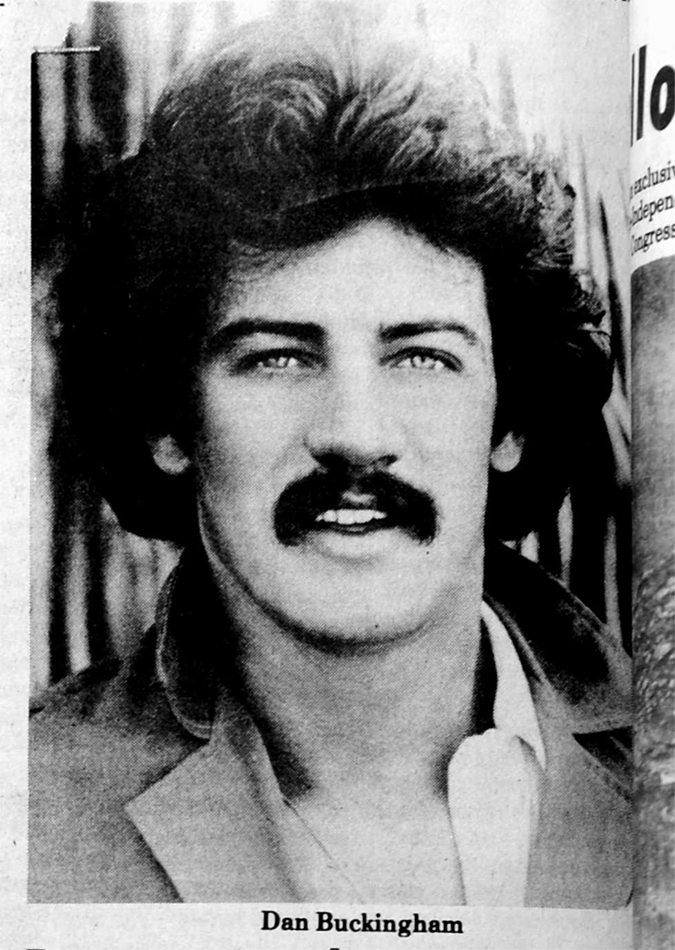

Buck worked in film and television, sold his visual art, opened a curio shop called Propinquities, edited a magazine called Melrose, and, according to Robert, modeled for the iconic Marlboro Man campaign, which featured the kind of rugged cowboys you’d find in Utah on U.S. billboards through the late ‘90s.

Robert recalls Dan’s studio bordering the Venice Beach Boardwalk, where he opened a garage door to sell art to passersby. Robert was visiting Dan when Arnold Schwarzenegger stepped in to buy a piece—perhaps Dan lived feet away from Muscle Beach with intent.

In his last days, Dan joked that Robert should cremate him, mix his ashes with cocaine and send the urn to friends in Los Angeles for good use.

The LA Times described Dan Buckingham’s work in 1988 as “large canvases covered in metal, plaster, and hand-dyed paper,” and confirmed his presence at LA galleries, in Georgia O’Keeffe’s estate, “as well as in the hands of many local collectors.” In an email, the author of these articles remembered Dan’s work having “religious and western motifs.”

After receiving his diagnosis, Dan went home with his brothers in Utah to die at the age of thirty-eight.

In his last days, Dan joked that Robert should cremate him, mix his ashes with cocaine and send the urn to friends in Los Angeles for good use. Robert did meet Dan’s real request—spreading his ashes at the brothers’ old campsite at Miner’s Basin, by a picturesque brook on Moab’s La Sal Mountains.

Last year, on Dan’s birthday, Robert drove me to Miner’s Basin. We hiked to a tree that was uprooting a metal placard with Dan’s name that read, “We love you.”

“Happy birthday Dan,” Robert said. “Jack, keep him out of trouble.”

Thunder rumbled and rain followed us back down the mountain. The rest of summer was stormy—always starting over the mountain, bringing some mountain to town, reforming sand banks, destroying roads, and threatening homes.

With each storm I wondered more about Dan. My world became measured against what I knew of him—and I wanted to know everything.

What was left of his Moab—of kids roaming freely, street parties and drive-ins, war drafts and recession? Would Dan and I have been friends, like his penpal? What traces of him remained, and what had washed away? In a desert town that folded itself into layers, where was he?

My world became measured against what I knew of him—and I wanted to know everything.

I talked to his classmates, dug through yearbooks and records. The storms became his storms, then our storms, because they charged life with purpose: find him, immortalize him.

And, I reasoned, what immortalizes us more than art?

Robert, the internet, the librarians at the O’Keeffe Museum—nobody had Dan’s work. If I could find it, could I communicate with him through time, around death? Would I be literate in the language of his metals, plasters, and papers dancing on canvas?

I found myself thriving in this analog field work. I was an alchemist searching for a soul sealed away in a scattered body of work, and I was sure to find him, decrypt him. That’s why I packed up the truck and drove to LA.

But God had scraped Buck’s LA out to sea and posted something new on top—buildings, names, and memories were gone. Even Schwarzenegger, his assistant confirmed, had no record, no memory of Dan.

Ernie, a family friend in luxury real estate, was my last shot. Surely he knew a collector who knew Dan, but the city was too big, too changed. He only remembered the Marlboro Man.

Real or replica? What did I expect once I found the art? For his ghost to burst through that Apple ad and pass me a cigarette?

I felt stupid for thinking Dan and I had some meteorological connection. I laid down in the truck bed and closed my eyes. The traffic was endless, humidity suffocating.

I thought about Robert. Before leaving I had brought him wine for us to drink by his fire.

Robert, who buried Moab’s dead, who lost the brothers who raised him to war and disease, lost his parents to addiction, lost the town he grew up in to the ravages of tourism, whose tears shone in the firelight as he asked, “Where did it all go?”

What did I expect once I found the art?

And Robert, who could still raise a glass to the memories. I couldn’t bring Dan back to someone who already let him go. Clink.

Was my desire to give Dan a solid form, or to give one to myself? If I spent the rest of my twenties piecing together his work, would I ever find enough of him to hide behind? Why was I neglecting my becoming to build this canvas of him? Was this canvas even of him? Real or replica?

I was reaching for an answer when thunder crashed into the hum of LA. I shot up, unable to find a cloud responsible, and my phone rang—an invitation to dinner from a new friend.

I felt the billboard watch me start my truck and turn onto Sunset—traffic had died down.