A Denver museum’s alleged act of censorship is stirring national debate, as stakeholders clash over who gets to tell the story—and who gets heard.

DENVER—Growing up as a transracial, transnational adoptee, Colorado-based artist Madalyn Drewno says she’s often felt that her own history and identity were being compromised, marginalized, or erased. “Adoption narratives,” she says, “are often forced upon us.”

Now, she’s alleging that one of her paintings depicting two members of the local Asian American community has been censored by a Denver museum. The dispute has swiftly gained national attention, drawing a statement from free speech organizations and coverage in Hyperallergic—even as the women depicted in Drewno’s painting say their voices are being lost amid the controversy.

History Colorado Center has come under scrutiny for excluding one of Drewno’s paintings from Big Dreams in Denver’s Little Saigon, an exhibition designed to elevate the voices of community members as part of a larger Little Saigon Memory Project.

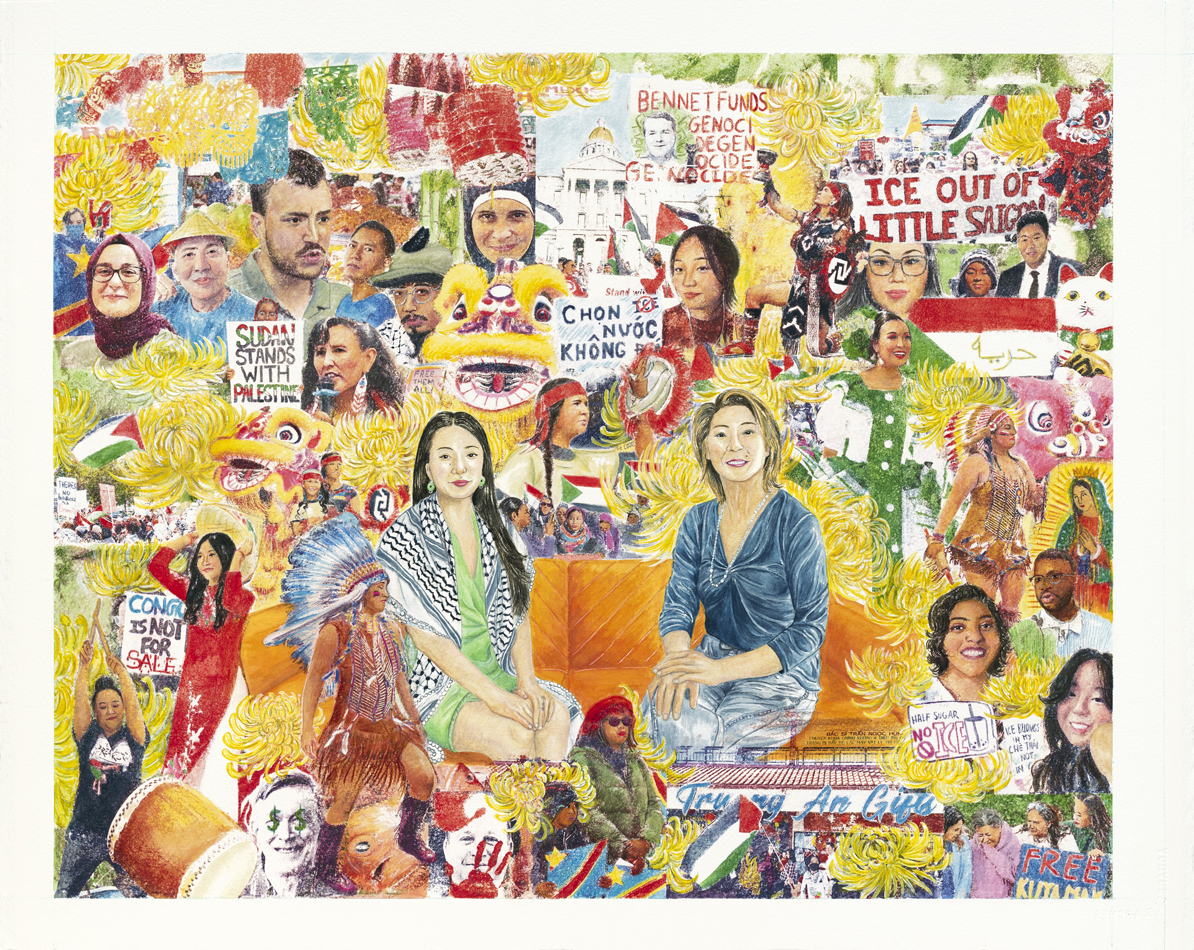

Drewno’s artwork, titled None of Us Are Free Until All of Us Are Free, includes critical portrayals of Colorado’s governor and two senators. It also features activists and protest signs addressing ICE immigration raids and genocide in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Palestine, and Sudan.

Indigenous dancers and Vietnamese performers are pictured as well, because Drewno wanted to “draw links between celebrations as a form of resistance.”

Big Dreams in Denver’s Little Saigon, which opened in late October and continues through early October of next year, was organized in partnership with Colorado Asian Pacific United, the organization that commissioned four artists to produce artworks for the show, including Drewno.

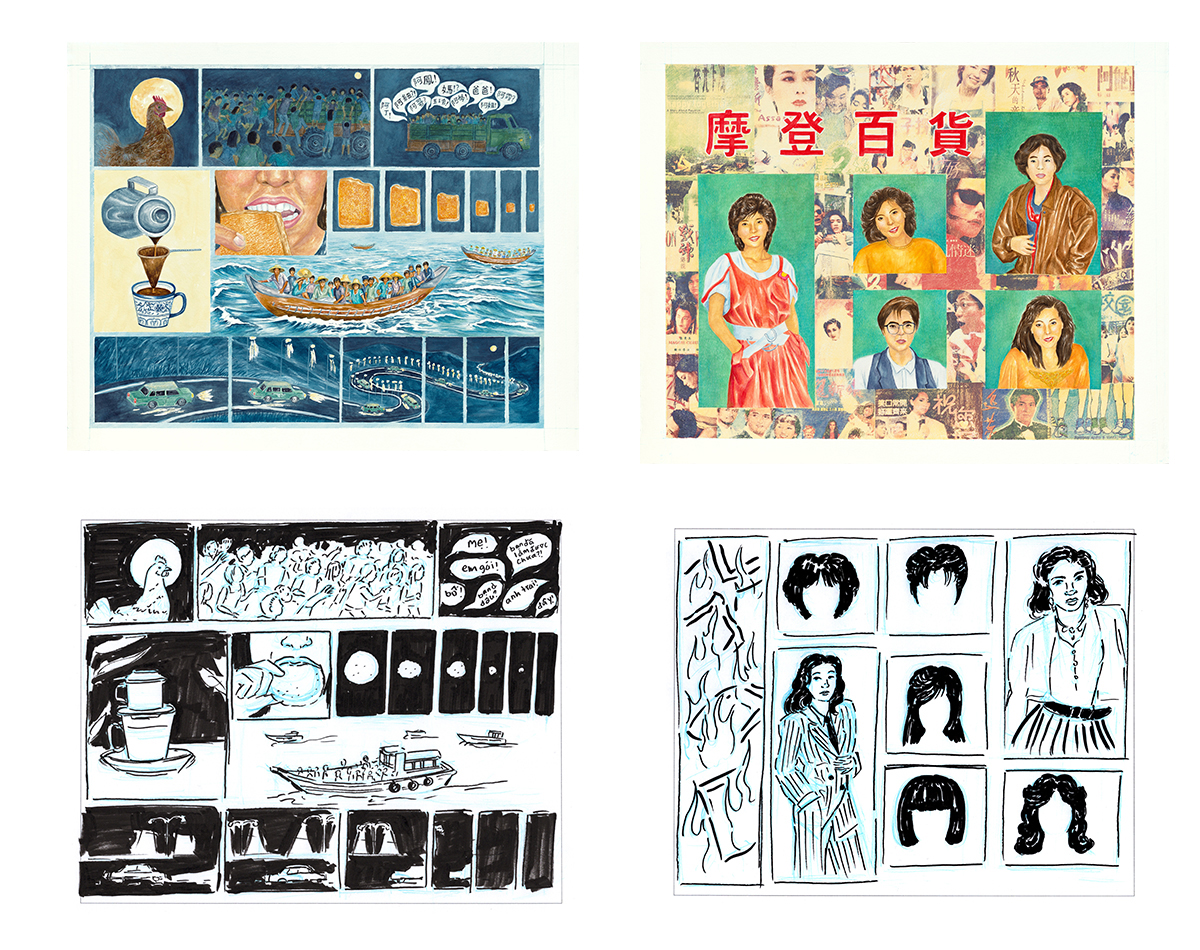

Drewno created a three-piece series, choosing imagery that spoke to honoring the past, refugee resilience, and the future. “The first two focus on individual experiences,” she explains, “and the third one looks at collective experience.”

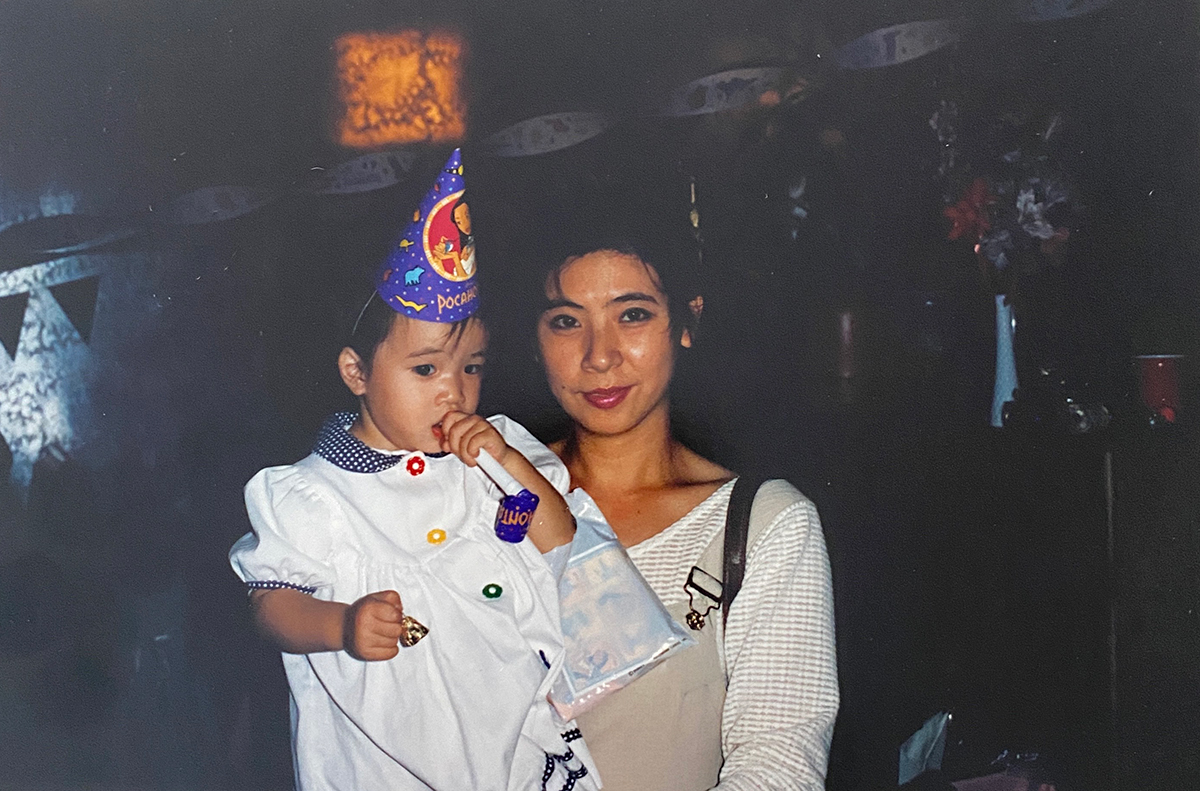

The series was inspired by oral histories shared by Ivy Ha, an Asian American refugee who fled Vietnam and established a successful boutique in Denver’s Little Saigon. Her daughter, Joie Ha, serves as executive director for CAPU.

It seems like her deeply personal stories about her refugee journey are important, but her as a human and individual are not.

“We were very excited and felt honored when Madalyn chose to use my mom’s story, and the pieces are very beautiful,” recalls Joie Ha. “Ultimately, it seems like [my mother’s] deeply personal stories about her refugee journey are important, but her as a human and individual are not.”

It’s a perspective rooted in the painting’s long journey from concept to creation and then censorship, the details of which have slowly unspooled in the public eye in the last week or so.

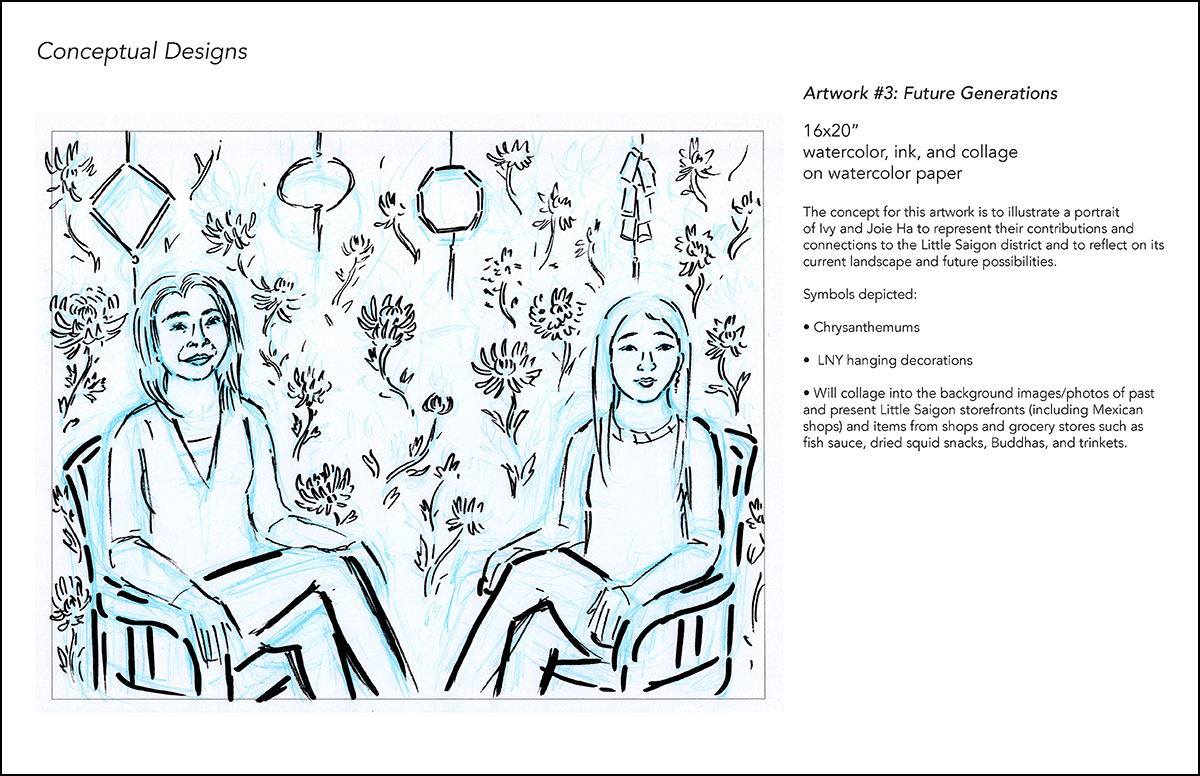

Both Joie Ha and Ha’s mother posed for a reference photograph taken by the artist, expecting the painting to feature a background with yellow chrysanthemums and additional iconography holding cultural significance—based on conceptual renderings Drewno submitted during the public call for art.

But the background for the finished artwork also includes Governor Jared Polis depicted with a red handprint, a symbol of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women movement. U.S. Senator John Hickenlooper appears with dollar signs over his eyes and U.S. Senator Michael Bennet is surrounded by text that accuses him of funding genocide.

“I was thinking about future generations, and to me that means thinking about how we can expand solidarity beyond our own community and the interconnectedness of our struggles, and how all these things have a shared cause of colonialism and white supremacy,” Drewno says of the piece.

Regarding the work’s content, Joie Ha shared in a November 10 email, “My mom was ambivalent about most of the decisions that Madalyn made for the piece in the context of the exhibit. She did not care for the politics or politicians in the piece, and her feelings have only intensified [about] being associated with it as the story grows.”

Ivy Ha shared her thoughts that same day, relaying them to me through her daughter who spoke with her by phone, then passed along this translation: “When I shared these stories, I just wanted them to be passed down to the next generation. I want people to see them and feel happy that the last generation went through so much and are now trying to live a life of harmony. Everyone can have their opinions, but the ones about the politicians in the painting are not from my story.”

Officials with History Colorado, a state-run agency within the Department of Education, say that showing the painting in its galleries would violate campaign finance law because it could potentially impact how someone chooses to vote.

I was thinking about future generations, and… how we can expand solidarity beyond our own community.

“The artwork unexpectedly included depictions of current candidates for office, and our long-standing practice is not to use public funds or resources as a platform for or against active political candidates, parties, and ballot issues,” Jason Hanson, chief creative officer with History Colorado, explained in a written statement I received via email on November 4.

“This practice is viewpoint neutral and informed by the Fair Campaign Practices Act, the Hatch Act, the IRS ban on political campaigning for 501c3 organizations, personnel policies, and… guidance from professional organizations such as the American Association of Museums,” Hanson added.

Colorado Asian Pacific United notified Drewno after learning that the work was being withheld, according to Jasmine Chu, CAPU programs and communications manager, who says the nonprofit “had hoped to find a solution so we would be able to include Madalyn’s artwork.”

Drewno responded to History Colorado’s decision by withdrawing her two additional artworks from the exhibition.

Then she reached out to Danielle SeeWalker, a Húŋkpapȟa Lakȟóta citizen of the Standing Rock Sioux Nation who recently settled a First Amendment lawsuit against the Town of Vail, another flashpoint in the region’s debates about artistic autonomy and institutional control.

This [museum] says that they value diversity and inclusion… when in reality they have silenced me.

SeeWalker, who had an exhibition at the History Colorado Center just last year, helped Drewno connect with the National Coalition Against Censorship. “Having seen her speak out really inspired me to speak out myself,” Drewno recalls.

Drewno says her decision to make the exclusion of her artwork public was partly because she feels it conflicts with “grounding virtues” that History Colorado outlines on its website as part of its “anti-racism work,” such as “being in community” and “amplifying and centering voices of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).”

“I wanted to hold the museum accountable through the public record,” Drewno explains. “My intention was to make the public aware of what happened because this is an institution that says that they value diversity and inclusion and uplifting voices in the community, when in reality they have silenced me.”

On November 3, the National Coalition Against Censorship, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, and the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado issued a joint statement condemning the alleged censorship of None of Us Are Free Until All of Us Are Free, arguing that depicting sitting public officials in artworks is not a violation of campaign finance law.

“This isn’t something we’ve ever seen before,” says Aaron Terr, director of public advocacy for the Foundation of Individual Rights and Expression, speaking about History Colorado’s decision to cite the Fair Campaign Practices Act as a reason to not show a work of art. “The artwork wasn’t made, commissioned, or selected for the purpose of promoting a political campaign.”

This isn’t something we’ve ever seen before. The artwork wasn’t… promoting a political campaign.

The statement suggests that there’s another reason Drewno’s piece was rejected, and the artist says she agrees.

The letter asserts, “Rather than a concerted effort to ensure compliance with election campaign finance laws, History Colorado Center’s attempt to suppress the display of None of Us Are Free Until All of Us Are Free seems more likely related to the pointed political sentiments present in the background of the painting.”

A November 3 press release from the organizations calls for corrective action:

“We urge History Colorado to take steps towards returning the censored artwork to its intended exhibition—with public acknowledgement of its error and a public apology to the artist.”

As of this writing, no such action has been taken.

Meanwhile, another controversy has taken shape.

After NCAC posted news of the censorship allegations and a photo of the excluded artwork on Instagram, other voices began to surface—including several that focused on the question of who gets to tell which stories.

While Joie Ha—CAPU’s executive director and one of the subjects of the disputed piece—was surprised by the political content of Drewno’s painting, she supported its inclusion in the show. But seeing an artwork depicting her family used as part of the anti-censorship effort stirred up an array of feelings in her family, who felt like they were being used as part of a “campaign” rolled out by the free speech groups.

Joie Ha requested that NCAC remove the post in a lengthy Instagram comment that included this language: “It is not right for you to use my family’s stories as a platform for your political agenda. My mother’s stories are sacred, it took me years for her to finally open up. They are not a commodity and you have taken away her agency.”

It seems like people are speaking about [my mother’s] story… but no one wants to hear her actual thoughts about it.

The NCAC responded in the thread for their post, and emailed a statement to me on November 5 that reads in part:

“As free expression organizations, our responsibility is to the public in revealing cases of censorship. Once an image has been censored, that image becomes newsworthy and it is important to see the actual art targeted by the government. But in recognition of Ms. Ha’s request, we removed the subject’s name and identifying details from our advocacy letter as it appears on NCAC, FIRE, and ACLU-CO’s websites.”

Joie Ha addressed the issue during a recent phone interview, sharing both her own perspective and explaining her mother’s reaction to the NCAC post. “My politics are aligned with Madalyn’s,” she says. “My mom is a refugee who escaped because of extreme oppression, so she gets very anxious when it seems she’s being aligned with particular politics because that was dangerous.”

She elaborated on her mother’s concerns, while sharing more of her own perspective, in the email she sent me on November 10.

“Since it is now in the public eye in this heated space, it seems as [though my mother] is implicitly agreeing with the sentiments in the piece regarding the politicians, and agreeing with the censorship case. Neither of which would be true,” Ha wrote, opening up about how the censorship story seems to have left the human story in its wake.

“But there is very little room for her opinion in this public sphere, and so it seems like people are speaking about her story and using it as a vector for these other issues, but no one wants to hear her actual thoughts about it.”

On November 10, Drewno released a statement on social media clarifying her stance on History Colorado Center’s decision to remove her work.

“This statement is to provide clarity around what happened with my artwork being censored,” she wrote. “It is also to emphasize that I shared this story to speak out against censorship—not for some supposed individual political agenda or campaign.” She added that all portrait subjects gave full consent and understood the work would be publicly viewed.

In her email on the same day, Joie Ha noted that “the main issue is the organizations did not think to consult us prior to publicly sharing [the image], nor did they consider any of the repercussions of publicly identifying us as if we were proponents of their campaign.”

Amid all the dialogue involving Drewno’s work, three voices remain conspicuously absent.

Thus far, neither Polis, Bennet, nor Hickenlooper have responded to my request for comment or provided a statement addressing the question of whether using their images in an artwork violates campaign finance laws.

Artists who work with state-run organizations really need to know what they’re getting themselves into.

This is just the latest controversy involving government intrusions into the arts, ranging from censorship allegations involving Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum in Arizona to concerns in New Mexico about federal strings attached to state art grants in the Trump era.

“We’re in a really weird climate right now,” reflects SeeWalker. “I know a lot of artists who aren’t showing or curating work in government spaces because of it. Artists who work with state-run organizations really need to know what they’re getting themselves into.”

Artists have responded to recent efforts to curtail creative expression in various ways, including planning acts of creative resistance for November 21 and 22 through the new artist-led Fall of Freedom initiative, whose Southwest participants will include Art Gym in Denver, The Projects|Space in Tucson, and Dallas Contemporary, among others.

Moving forward, Drewno says she’s hoping to have another opportunity to show all three paintings, and may end up organizing a grassroots group exhibition of “censored art or rejected art.”

“It really calls into question whose stories get to be told, which stories are chosen, and who they are being catered to,” Drewno says of her History Colorado experience. “I really hope this will help people think more critically about all institutions and narratives.”