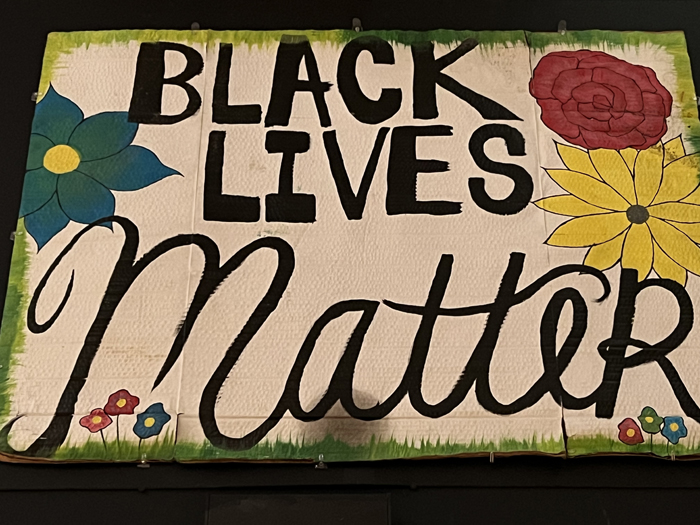

Twin Flames: The George Floyd Uprising from Minneapolis to Phoenix at ASU Art Museum displays signs, artworks, and other community offerings from George Floyd Square.

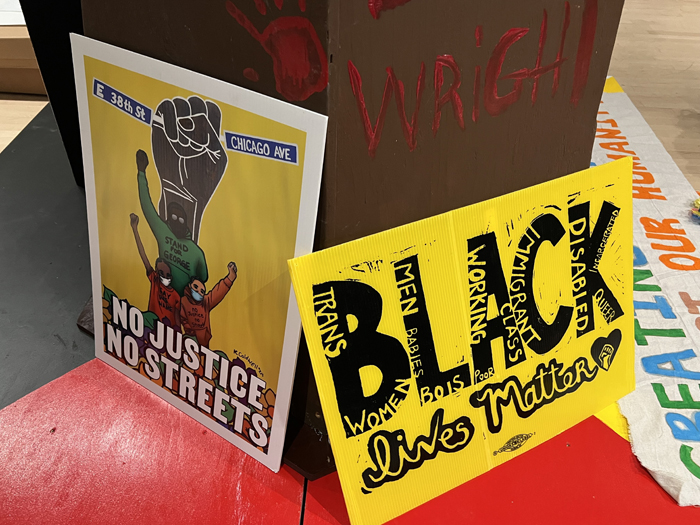

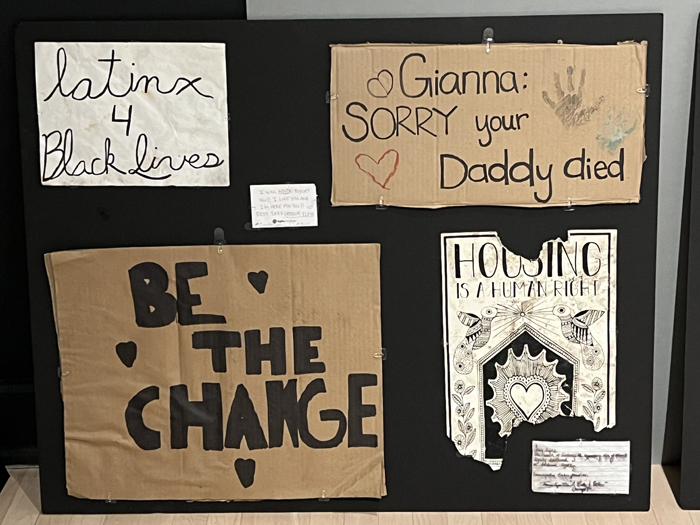

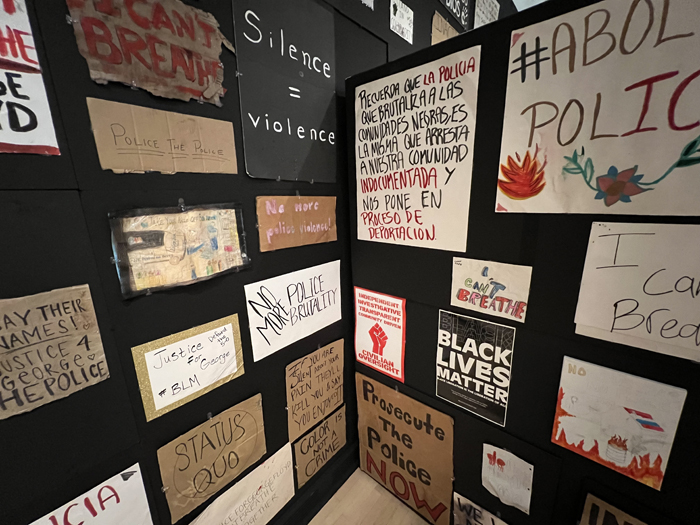

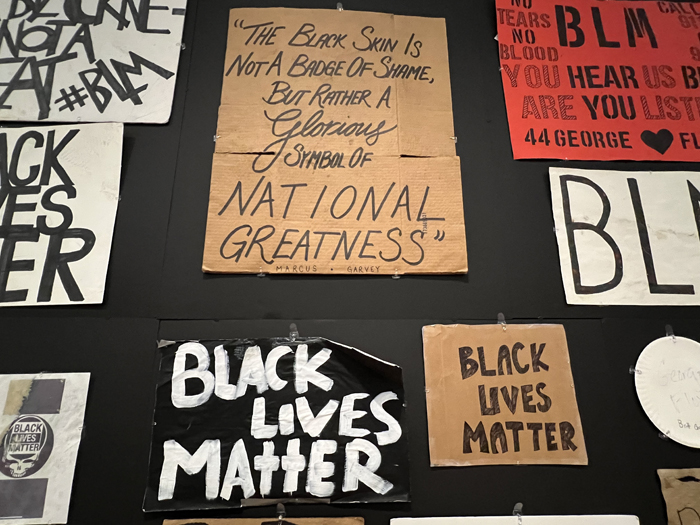

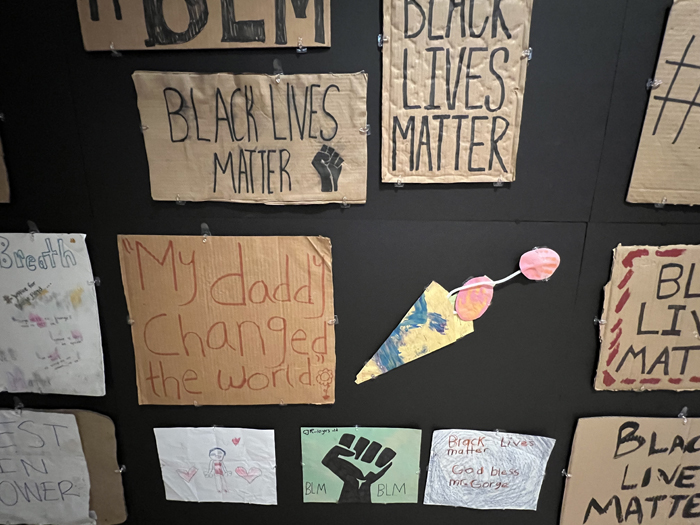

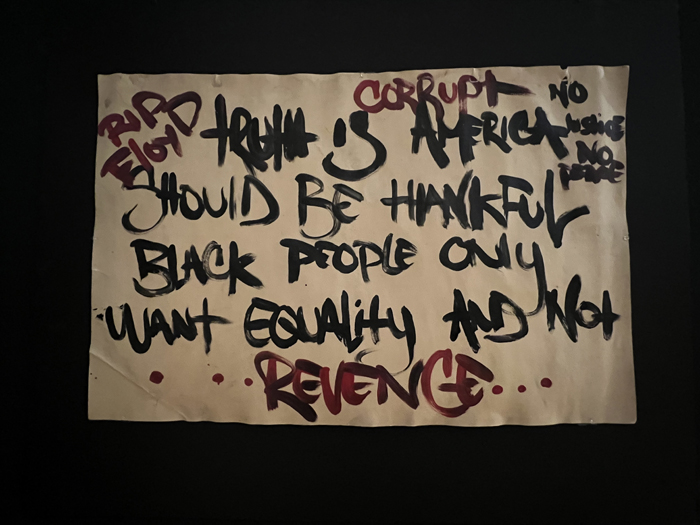

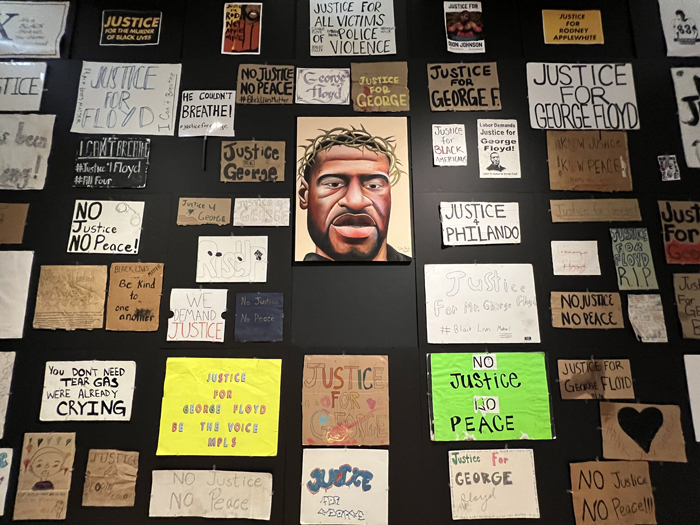

TEMPE, AZ—Justice for George. He couldn’t breathe. Let’s change the fucking world. Trans Black Lives Matter. Stop the genocide. You don’t need tear gas, we’re already crying. My daddy changed the world.

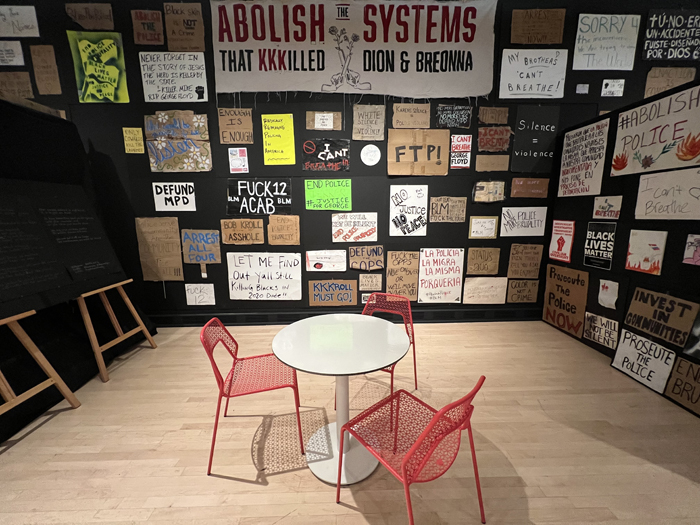

These phrases are found on several signs hanging inside a gallery at Arizona State University Art Museum in Tempe, where the exhibition Twin Flames: The George Floyd Uprising from Minneapolis to Phoenix opens February 3 and continues through July 28, 2024.

It’s the first formal museum exhibition featuring a vast selection of objects left at the Minneapolis intersection where George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, which gave rise to the ongoing public memorial George Floyd Square in Minneapolis.

Rooted in early neighborhood protests and remembrances, the show ultimately evolved through the work of myriad individuals and groups in Minneapolis and metropolitan Phoenix, a region mired in allegations of police misconduct.

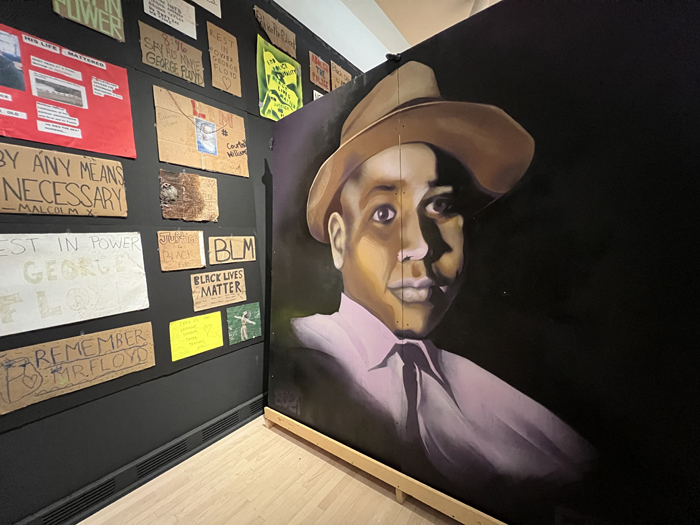

“When George Floyd was lynched, it hit people’s points of pain,” says Minneapolis-based George Floyd Global Memorial executive director Jeanelle Austin, who spoke with Southwest Contemporary about the initial protests and their societal context and the exhibition’s origins.

Austin says she’s deliberate about using “lynching” because the word references an extrajudicial killing in an undue process for social control and signals to Black people everywhere that this can happen to them if they step out of line. “It was the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

At the time, early COVID-19 restrictions were in place, and the list of Black people recently killed by law enforcement officers had grown to include Breonna Taylor in Kentucky and Dion Johnson (who died the same day as Floyd) in Arizona, among others.

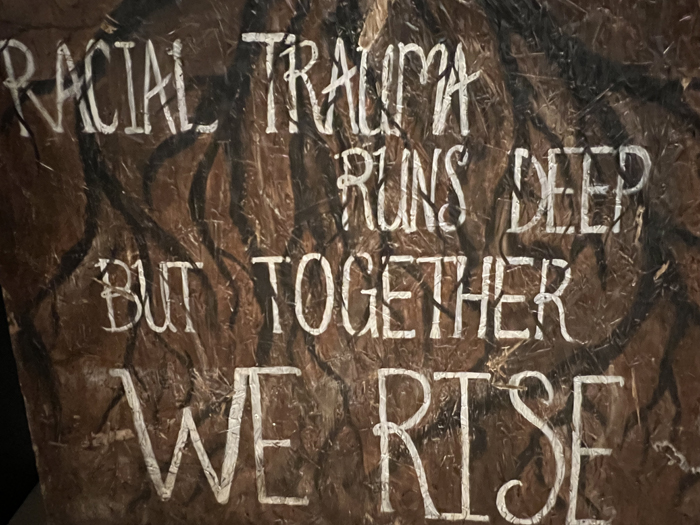

“Everything seemed to be on pause except for the killing of Black bodies. People hit the streets, coming to hold space and grieve, and an organic memorial that became a sacred site of pilgrimage began to grow,” Austin says about George Floyd Square.

Over time, various community members and organizations worked to preserve the objects left at the square, which Austin describes as “offerings.” They had about 2,500 in 2020 but now her organization is working to archive up to 10,000, she says. “We realized they were created for the purpose of protest so we didn’t just want them stored on shelves.”

Before the Tempe exhibition—presented by ASU Art Museum in partnership with the ASU Center for Work and Democracy and the George Floyd Global Memorial—select offerings had been shown at various pop-ups around Minneapolis.

How did the exhibition end up in Arizona, where the City of Phoenix and the Phoenix Police Department have been under the United States Department of Justice microscope? In August 2021, the DOJ announced a civil rights investigation of the Phoenix Police Department for excessive use of force, retaliation, discriminatory policing practices, violating the rights of unhoused and differently-abled people, and other allegations.

In 2022, the George Floyd Global Memorial auctioned exhibition opportunities during a fundraising gala, and ASU came out a winner, recalls Rashad Shabazz, an ASU faculty member who was there that night and went on to become one of the exhibition’s five organizers along with Austin.

Together, organizers rallied dozens of people who helped inform which works would be included in the community-based exhibition that also displays several pieces created in Arizona.

“We began by selecting things that reflected our own experiences with policing here and in other parts of our lives,” recalls Shabazz, an associate professor at the ASU School of Social Transformation. Some items came from other protests, and several reflect additional concerns, such as injustices committed against Indigenous and Latinx community members.

The exhibition is organized into five sections: Say Their Names, Justice, Black Lives Matter, Community Brings Safety, and Solidarity. ASU Art Museum curator Brittany Corrales, one of the exhibition organizers, guided aesthetic considerations.

Museum steps leading to the gallery will feature the names of forty-two people killed by law enforcement in Maricopa Country (where Phoenix is located) since 2013, a figure reported by the national research collaborative Mapping Police Violence.

Inside the gallery, visitors will see a large-scale portrait of Emmett Till, a Black teen lynched in Mississippi in 1955, and the wooden sculpture of a raised Black fist that artist Jordan Powell-Karis first placed at George Floyd Square years before driving the artwork to Tempe and personally installing the piece for this show.

The exhibition includes The Free State of George Floyd (2021), a short film documenting community actions at George Floyd Square, and a billboard with Floyd’s image near the museum exit.

A gallery handout expands on the exhibition’s five themes and addresses related issues such as historical and contemporary monuments, the history of art and protest, and practices related to conservation and care. In a separate museum space, visitors can create their remembrances with the option of adding them to an ofrenda-style community altar.

“The museum centers art in the service of social good and community well-being, so this exhibition is very aligned with our mission,” explains Corrales, who adds that related programming will include a dance party on opening night, a presentation about the history of art and music in protest, and a screening for the 2022 film Stonebreakers that explores controversies related to public monuments.

ASU Art Museum director Miki Garcia notes that the museum also focuses on increasing Black representation in its collections, exhibitions, and programs through the Black Arts and Culture Council, which ASUAM created in February 2023.

“When George Floyd was murdered, the uprising on all seven continents called out institutional and systemic racism, so it was a call for the museum field to reinvent what museums are for,” reflects Garcia.

As the George Floyd Global Memorial considers future exhibition options, Austin says she expects this first museum iteration to provide valuable lessons.

“This will serve as a model for what we could do in other cities,” she explains, “so we’re paying close attention to how we could do traveling exhibits, but also what people will experience when we build a museum.”