Montgomery, Alabama

My third-grade field trip to a State Capitol was a muggy school-bus ride to Montgomery, Alabama. We visited the requisite sites, including the state senate chambers and a life-size statue of Jefferson Davis. We were taught that the Capitol building was the first headquarters for the Confederacy during the Civil War, which was fought to preserve “states’ rights.” Rights to do what? is a question nobody asked.

A field trip like this is not uncommon for children in the Deep South. People learn the history that is available to them, so it’s especially significant that the National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened earlier this year in Montgomery, a city that also contains fifty-six monuments to the Confederacy. To approach the memorial, an uphill path leads to a series of rectangular corten steel pillars. They’re the same scale as a human body, and they stand at ground level, which encourages that association. Incised into each of the pillars is a county and state name and a list of people: those who were lynched in that county during Jim Crow. As viewers walk through the field of steel markers, it first seems right and reverential to stop at each one and to read those names. Quickly, that goal becomes insurmountable. There are hundreds of pillars, thousands of names. As one walks, the ground slopes downward, and the pillars lift from the ground and hang from a massive armature above. Finally, the viewer stands below hundreds of hanging bodies, sunlight streaming through the rows.

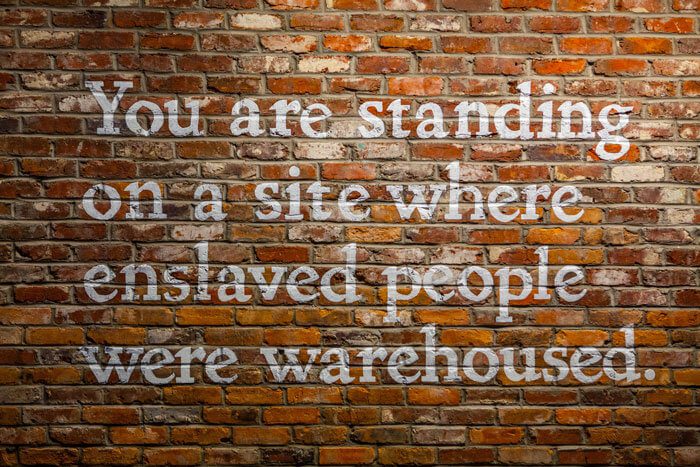

If the memorial is a case study in how abstraction can incite empathy, text painted on the wall inside the entrance to the Legacy Museum, which accompanies the memorial and is a five-minute drive away, makes clear its refusal to truck in metaphors: “You are standing on a site where enslaved people were warehoused.” A map shows the locations where slave traders set up shop near the Alabama River, where Montgomery grew into a bustling slave-trading port in the burgeoning United States. The museum is a tour-de-force display of racial inequality and violence in America, and a variety of forms and technologies ensure that the learning experience is tactile and visually compelling. Especially affecting is a series of vertical scrims showcasing newspaper advertisements for the sale of slaves: “always does what he is told,” “strong and obedient,” “a good breed.” Like much of the museum, these dehumanizing praises evince the ways in which racism and oppression are embedded in the capitalist system that encouraged practices like the slave trade, as well as mass incarceration today. As violent and unjust as this history is, it’s a history that visitors to the memorial and the museum won’t be able to ignore; perhaps visitors might get a little closer to understanding and grappling with its legacies. As a neon work by Glenn Ligon entreats toward the museum’s exit, “WITH HOPE.”