In a David Bowie–inspired show in Scottsdale, Steven J. Yazzie and Erika Lynne Hanson confront earthly disillusionment through landscape-based abstraction.

Inspired by David Bowie’s 1971 song “Life on Mars?”, an Arizona curator brought together two artists focused on landscapes, imagining how their work might speak to its themes. Bowie’s lyrics have become their own constellation in the cultural firmament—“Now she walks through her sunken dream… and she’s hooked to the silver screen”—denoting the human impulse to terraform new realities amid environments that disappoint or disappear.

The artists had never met. They lived nearly 1,000 miles apart. And neither was familiar with the other’s work. But Lauren O’Connell, curator of contemporary art for Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, felt there were meaningful connections between the artists’ vastly different engagements with landscape and environment. So she suggested a collaboration, with Bowie’s lyrics about a girl trying to escape reality through cinema as a prompt. And the artists were game.

Despite the song’s interstellar title, the artists zero in on… its themes of worldly disenchantment.

Once O’Connell offered the point of reference, she let artists Steven J. Yazzie (Diné, Laguna Pueblo, European ancestry) and Erika Lynne Hanson determine the directions they would take. “It was exciting,” says O’Connell, “to see them both respond curiously and positively to each other’s practices, opening new avenues for contemplation and conversation.”

Today, the collaboration between Colorado-based Yazzie and Arizona-based Hanson is manifest in the Life on Mars exhibition at SMoCA, which continues through September 14, 2025. Despite the song’s interstellar title, the artists zero in on—and deconstruct—its themes of worldly disenchantment. The exhibition has become a prompt in its own right, challenging viewers to consider whether there might be new ways of perceiving and experiencing realities right here on Earth.

The artists pull us towards similar conclusions, but use distinct approaches for getting there. Still, the show illuminates some compelling parallels.

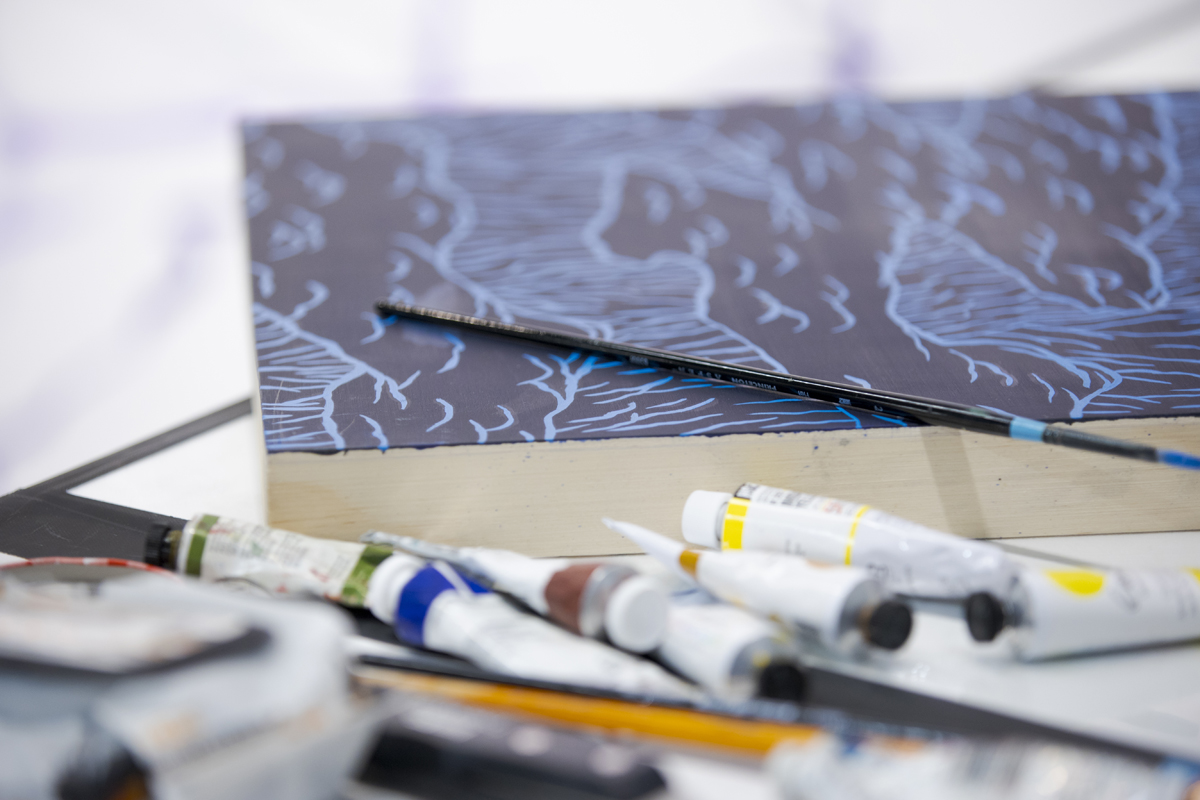

Both artists inspire reflections on nonlinear conceptions of space and time, using abstraction and multiple mediums such as video, sculpture, painting, textiles, and ceramics to push past the limits of anthropocentric worldviews and identities while conveying the exhilarating beauty of realms beyond human constructs.

“We both approach landscape and abstraction in a similar way that’s based on residues of places we’ve experienced rather than real places,” explains Hanson. “We’re using abstraction to get at what you can’t get at through language.” Yazzie describes abstraction as “a way of fighting against something literal while playing with this space in between.”

It’s most evident in Yazzie’s surrealistic oil on canvas triptych Night-Dawn-Day-Dusk (2025) and in Hanson’s weavings made with linen, lurex, wool, and wood, in which the relationships between forms suggest shifting, overlapping, transmuting realities.

“I’m really leaning into the metaphysical aspects of my work,” reflects Yazzie, who draws on personal experiences of the land, including the Navajo Nation where he grew up, in works that enmesh memories, collapse time, and merge the terrestrial and celestial.

Whereas Yazzie draws on spirituality, Hanson is grounded in science.

“My work is very research-based,” says Hanson, describing her site visits to locations such as intriguing geological formations and rock quarries mined for landscaping decor, plus her readings on post-human ecologies.

For Replicants, or a gesture that won’t stop erosion (2025), Hanson created sixty fist-sized sculptures with gypsum cement and pigment, arranging them in ten neat rows on an expansive wall, where they suggest the order imposed by human infrastructure and its radical diversions from how geologies exist in the wild.

[The land is] where our stories come from and where they go back to.

Nearby, there’s Yazzie’s Constellation (2025), a floor installation combining ceramic, earth, and sound. Yazzie worked with Arizona-based artist Mike Prepsky to realize its five ceramic forms by rolling out slabs of clay, then throwing the material onto trees, giant rocks, and other desert forms in South Phoenix.

Yazzie reflects, “As I’ve gotten older with my work I remember how land is ultimately… everything that we are and where we come from. It’s where our stories come from and where they go back to.”

For Yazzie, the Southwest is “a place of conquest that’s been politicized” but also a place that’s “constantly in motion and a place of healing.” Hence, he sees Life on Mars as “a way to remind myself and others of the pure aspect of nature or the idea of nature, allowing people to think about their own relationship to the land.”

Hanson hopes the museum collaboration will help others have greater awareness of their relationships to non-human entities.

“Maybe people will think more about human and geologic relationships, paying closer attention and having a deeper understanding for what those relationships mean in their own lives,” says Hanson. “So often we have empathy for animals and plants, but typically that’s not extended to the geologies that surround us.”

Perhaps, like the girl in Bowie’s song who quickly becomes disillusioned by the silver screen that allegorizes humanity’s impulses towards space travel, viewers will indeed become more centered on the environments they populate and the infinite wonders they entail.

Never mind Elon Musk’s hopes of colonizing Mars. As Bowie wrote, “Oh, man! Wonder if he’ll ever know/He’s in the best-selling show.” These artists have something vastly more expansive and transformative in mind.