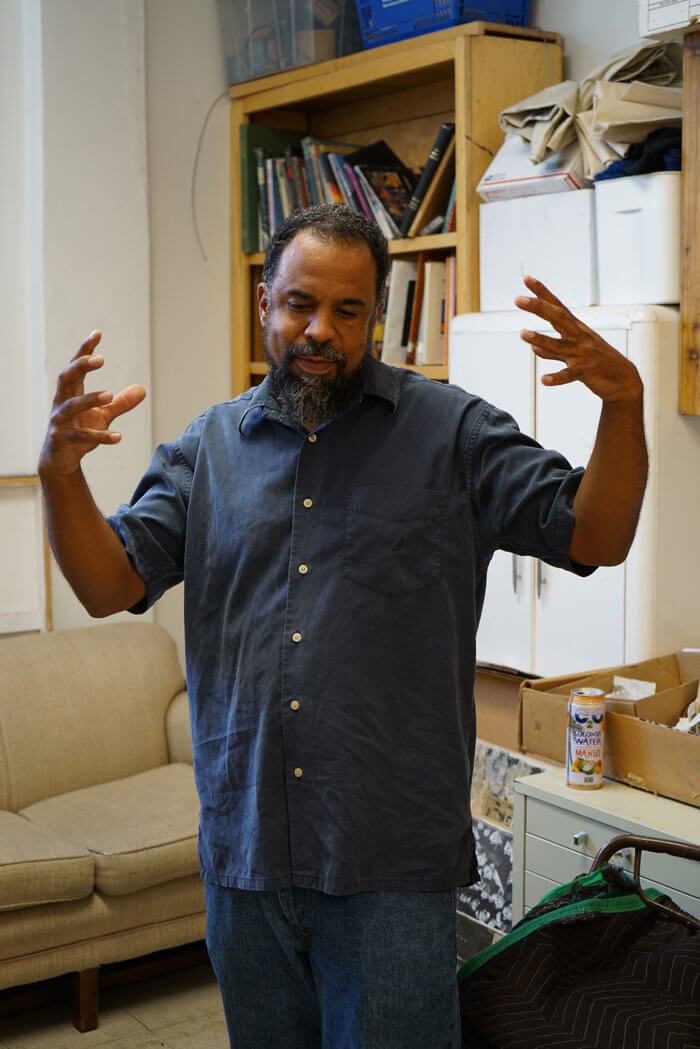

In Karsten Creightney’s painting studio at Sanitary Tortilla Factory in downtown Albuquerque, there is a massive pile of paper scraps: richly colored vintage advertisements, newspaper clippings, blown-out images torn to bits, an array of textures, colors, and weights. This is the stuff of dreams for the artist, a deep well of source material from which he builds his paintings. He has an almost magical way of collaging the surface so that the patterns peek through amidst his compositions, hinting at other pictures, other lives, other voices.

He has a second workspace in downtown Albuquerque—a print studio, which is also full of paper. Spending time in both these spaces allowed me to see how Creightney moves fluidly between two media and how he brings them together in a wrestling match of aesthetics and meaning.

Creightney received his BA from Antioch College and went on to complete the Professional Printer Training Program at the Tamarind Institute and receive an MFA in painting from the University of New Mexico. His most recent solo exhibition, Occupied Territories, opened in September at Exhibit 208 in Albuquerque and is on view through October 6, 2018.

Nancy Zastudil: I’ve seen several of your works exhibited in Albuquerque, but this is the first time I’ve been able to talk with you about your art. What keeps you interested, what compels you to keep making?

Karsten Creightney: I think that my work reflects me. I am somebody who has a multitude of interests, one of which is printmaking and the other is painting. Mine is a mixed-media process—I’m never satisfied to do things in a simple way. Early on, it started with two-dimensional versus three-dimensional works, and I was bouncing back and forth between the two. I think I get a lot from always experimenting, always kind of being a novice, never quite getting everything mastered. When it starts to feel like that, then I bring something else in to complicate it, to knock it back, to bring it to a point of struggle. I don’t have this idea that I am trying to illustrate perfectly out of my head. It’s not like that.

Is there any kind of narrative that guides or informs your images?

I wrestle with this idea of narrative. Some of my work is very literal and can be seen as didactic, but I go back and forth from making work that is loaded to work that is more open.

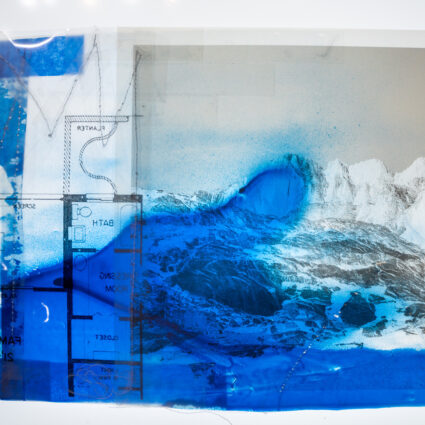

For me, it’s also this idea of excess. I start by putting a bunch of stuff—paper—on the canvas, based on a grid. The paper starts in scraps, and so that grid formation comes naturally from the rectangular form. Then, at some point, I try to start pushing and pulling to create a sense of space. Where the printmaking comes is in the layering and building up—and in the material of paper. Japanese paper is something I first encountered in lithography; sticking it to another piece of paper is called Chine-collé in printmaking. I love the shift in color; there is always an amber quality, and it does something for the rest of the paper.

Talk to me about the flowers in your works.

What to say about flowers? It’s pretty well-trod territory! But I love the forms; I love the color. There is something very joyous and childish in my relationship to these forms. I thought of them, especially in graduate school, as off-limits subject matter. But I quickly gave up the idea that my work would be so-called “smart,” and I just wanted to make it truer to myself and what I like. I think there is a naive quality to my work, and I embrace it through the form of the flowers. I try to do something different with them, something that is mine, that looks like I did it. I guess we all do that.

Do the flowers act as characters for you?

Sometimes, yeah. I think they stand in for people in some cases. In a lot of my works, they pop up, sort of like a figure on a stage. They occupy the composition in a way that feels propped up or a little bit artificial, like a flower portrait almost. I think that is what first attracted me to this way of working—using these forms and then trying to make interesting compositions with negative space, a singular, isolated flower against a backdrop. Eventually it’s led to these big landscape pieces.

An element of your paintings that I am drawn to is your use of exaggerated or magnified pixelated dots, which I associate with “print” in a generic way. I’m trying to figure out if I respond because it feels nostalgic, or maybe it’s a texture thing, or an art-historical reference. How do the dots function for you?

There is a reference, an immediate homage, for people who recognize where I’m getting this stuff. I’m definitely a copier. That’s how I learned, and I still outright copy from my heroes. I think it’s fun, and it comes back to this idea of the joy of making this stuff and not taking it too seriously—not needing to have everything be extremely rendered, that it can break apart into fields of tone. Visually I like that the dots create a buzz; they kind of hum in your peripheral vision. It’s also a way to blur things, to knock them back visually. Oftentimes I’m going for—or I’m trying to find—something that is familiar but doesn’t quite make sense. A bit fractured, kind of like Frankenstein: it works as a whole, it’s alive, it functions, but clearly it’s not perfect. It has a broken, fractured quality, and to me that is really more honest. The honesty of trying to let the viewer into the process and letting them know that it’s not easy.

Little spots of color give lots of opportunities for this jazzy excitement that can happen. I want to be excited by little happy accidents in my paintings. I like to set up spaces for that to happen.

References to Roy Lichtenstein—probably more so than Andy Warhol, for me—and Sigmar Polke are in there. It’s very conscious… thinking of Palm Trees, where Polke painstakingly created a four-color separation, but it’s all paint. He makes this thing that looks like it’s been printed on an offset printer with dots way too big, but it’s all paint. What that does as an image for me… it floored me the first time I saw it.

Is this falling apart of the image and bringing it back together connected to your ideas of wrestling an image?

What the dots do visually is talk about this larger idea, a constant desire to break things apart and bring them back together. Also, from a very technical point of view, you can blend two colors together or put them right next to each other. With complementary colors, you get brown, but set right next to each other you get that sort of electric reaction. Little spots of color give lots of opportunities for this jazzy excitement that can happen. I want to be excited by little happy accidents in my paintings. I like to set up spaces for that to happen. I think the dot thing came around because I like to introduce little bits of information, sometimes conforming to a shape, or as a way to push things back, or to introduce bright colors that on their own would be too much. But as little bits, it’s not going to be too distracting.

And when the texture or pattern of the underlayer starts to show through, it does something similar.

There is this idea of struggle. I think often that I’m trying to make two things that have no business being together fit together. That is part of the nature of collage. I love when I can make it work and still allow for some of that info about what it was before to be carried into the piece. There is a little story of what it used to be.

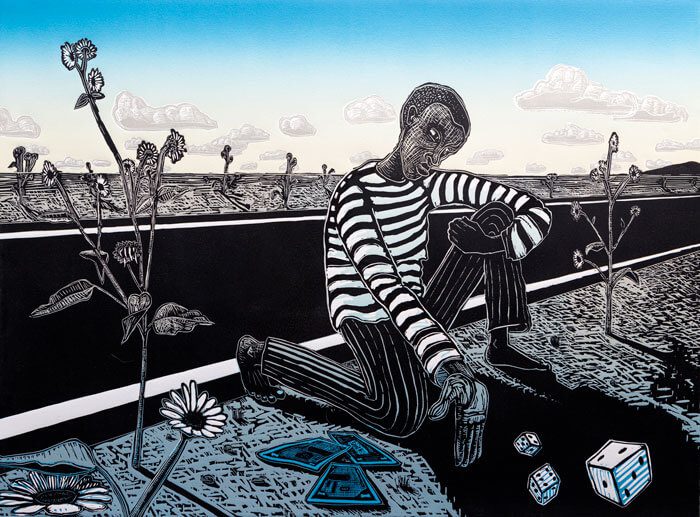

The figures in your work, for example the men playing dice at the side of the road, seem to carry some weight even though your treatment of them is different in each of the works. Translating that image through your hand takes it beyond representation to a more metaphorical or symbolic level. How do you settle on what figure(s) to include, and how much meaning to give them?

For me, that meaning is, in one sense, an inside joke—playing by the side of the road, being in this place that maybe isn’t the best place to be. The gambler…

…the roll of the dice and…

…and all that comes with that.

Part of why I use that image is because I have two uncles who are photographers, and one left me his negatives. So, there’s also this looking back in time to my family and through his eyes, and seeing these pictures of another time, and making that part of what I do. I find that to be very satisfying.

I think I use the flowers in the same way. There is a flattening to how I do it, this thing that interrupts the picture plane. As the viewer, you have to believe in this space, use your imagination to create that space. The road is super exaggerated, a one-point perspective is another way to create this idea of receding space… and then how all the elements occupy this stage. I often put little bits of information right at the edge, to lead your eye to the edge of the painting, to think about what’s beyond. The more I do, I discover more what it is.

Is repetition part of your process?

I hate to hear myself say that it’s about process, because as artists I think we need to get beyond saying that. But for me… within the process, I discover. I can never predetermine the outcome. So I get jazzed by this very basic idea that I repeat time and time again images that are essentially the same, but I come at it in different ways; doing it again and again and figuring out what is different. There is so much that I can respond to in laying down a field of information that is free of representation, at first. Which is what I do with the paper, all the underlayers—I love having those parameters to work with.

I think we are at a time when people are realizing that the way we have explained things away for so long is no longer working. And I think people are freaking out about it. We’ve been shaken. There’s a lot of change that is possible when things are shaken to their cores.

There is a writer, Sarah Sentilles, who I heard recently talk about the making and the unmaking and the remaking of the world, in terms of what artists do. Something about that is comforting to me when thinking about process. It starts to get at a larger meaning of what process is about—negotiating the world around you, your world—and why it’s important to be in the studio, engaged in the act of making and thoughtful about creating and process, especially now.

That really resonates with me. This thing about my way of making sense of things, that may or may not reflect the world—maybe more reflecting the way I want it to be, or the truth that I find, which may be different than what is out there. I think we are at a time when people are realizing that the way we have explained things away for so long is no longer working. And I think people are freaking out about it. We’ve been shaken. There’s a lot of change that is possible when things are shaken to their cores. Yet for me, it’s such a slippery slope when engaging in politics.

In some of his writing, Robert Irwin dismisses art making for political means, explaining that art made in the service of politics is just that; that’s what it is. But I see it every day: art that is just telling me something I’ve already heard or already agree/disagree with. I made two pieces after the shooting of Walter Scott. I just wanted to make something that was screaming my thoughts on the subject. Right now, I feel like we need more art like that, not less. We get these messages that there are certain ways to make art, and I wrestle with that within myself, because when I encounter art that is bad, and it’s poorly done and…

…and it’s trying to have some message…

That’s the worst! When someone thinks they are telling you something deep, but they didn’t really work that hard to do it.

What I miss in really didactic work is the chance to contemplate, to see and consider something I don’t immediately know the answer to.

Right. As an artist, I’m trying to reconcile those two impulses within myself. A lot of what I do is reactionary, because there is this need to get through it, to react to the world and get through it. Black Hills, the landscape painting, is very much a reaction to the world. It’s a picture of the Black Hills, which has a very problematic history. It’s my way of trying to come to grips with that. It’s my question to myself and everybody else: Given this history are we just going to accept it, to say that is just the way the world is? Hopefully that piece allows space for those questions to be asked—not necessarily asking a question and then shouting the answer.