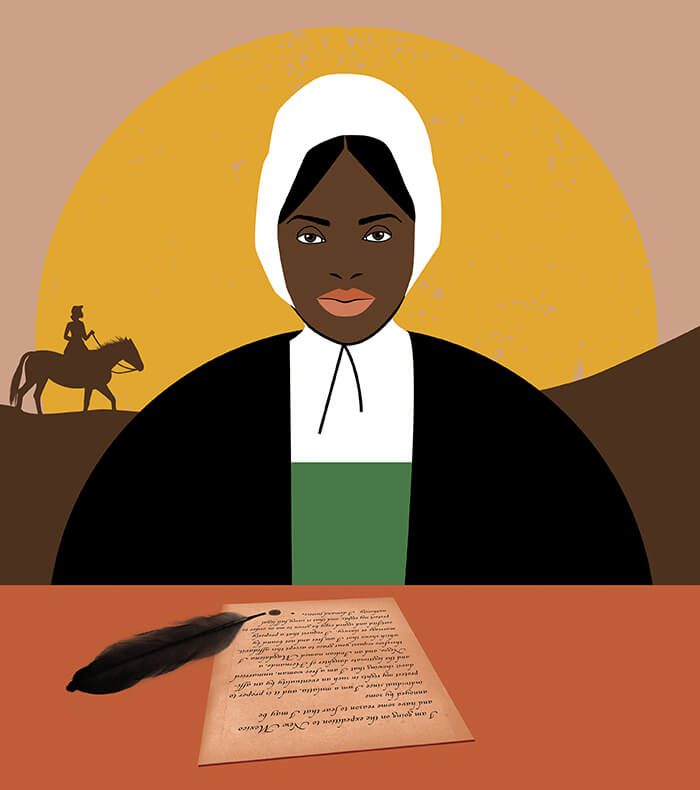

Name: Isabel de Olvera

Born: Querétaro, Mexico, sometime in the 1500s

Died: Northern New Mexico after 1600

Role: Among the first free black women in Northern New Mexico.

Known for: Demanding her rights as a free, single woman in writing in 1600.

Quote: “I demand justice.”

Where are the black women in colonial New Mexican history? Typically, the 1500s and 1600s are defined by a series of male Spanish conquistadors and governors whose names litter the city: Coronado, Peralta, De Vargas. Their expeditions brought soldiers and their families to what they called northern New Spain in efforts to “settle” land that had been occupied by indigenous pueblo peoples since the thirteenth century. The horrors inflicted on the pueblo peoples are glossed over in modern day celebrations of the Entrada (De Vargas’s mission to retake Santa Fe and its surroundings) and the Fiestas. In an effort to affirm the survival of Catholicism and Spanish bloodlines, the existence of other faiths and ethnicities are denied.

Isabel de Olvera challenges all of that. In 1600, she joined Juan Guerra de Resa’s expedition to New Mexico as a servant to a Spanish woman. De Olvera referred to herself as a mulatta, with an African father and a native Mexican mother. She was one of a significant number of black and mulatto men and women who came to New Mexico during the colonial period, though most of their stories were not adequately recorded.

In a deposition made before the governor of her home, Querétaro, Mexico, Isabel de Olvera inserted her voice and her story into the historical records of the time. Before three witnesses, free black Mateo Laines, mestiza Anna Verdugo, and black slave Santa Maria, she bid for protection on her journey and once she reached New Mexico. She declared, “I am going on the expedition to New Mexico and have some reason to fear that I may be annoyed by some individual since I am a mulatta, and it is proper to protect my rights in such an eventuality by an affidavit showing that I am a free woman, unmarried, and the legitimate daughter of Hernando, a Negro, and an Indian named Magdalena.” Not only was she free from slavery (the Spanish ruled in 1542 that any person with a free mother was also free), she was unmarried and included a mention of her single status. Obviously, she was afraid to travel to a new colony without some confirmation of her freedom and her autonomy, realizing that as a single woman of color she might lose her rights and freedoms in a new place. She continues, “I therefore request your grace to accept this affidavit, which shows that I am free and not bound by marriage or slavery. I request that a properly certified and signed copy be given to me in order to protect my rights, and that it carry full legal authority. I demand justice.”

What became of De Olvera once she arrived in New Mexico is unknown. The main records of black and mulatta women from this period come to us from church documentation of marriages, baptisms, and burials—and from court cases regarding witchcraft.

De Olvera’s words are powerful and still ring clear across the centuries. Traveling with seventy-three soldiers, food, livestock, and other supplies (including nails, powder, medicine, boots, silver daggers, silk hats, linen shirts, and eight hundred bars of soap), some scholars suggest that her statement may have been a means of seeking protection against the advances of soldiers along the way. What became of De Olvera once she arrived in New Mexico is unknown. The main records of black and mulatta women from this period come to us from church documentation of marriages, baptisms, and burials—and from court cases regarding witchcraft. Historians suggest that women of color in New Mexico sought power over their precarious situations and often abusive husbands by drawing on the help of local curanderas, medicine women, which resulted in witchcraft accusations. Others appealed to governing bodies for protection of their status as free women. De Olvera’s statement is an incredible explication of a black woman’s attempt to navigate a patriarchal and Spanish-dominated system that was set up to keep her powerless. She exemplifies the ongoing intermixing of indigenous American and African peoples, the construction of race in colonial North America, and the presence of black women in New Mexico from its earliest written records.

To read more about the history of black women in the Southwest, see African American Women Confront the Southwest 1600-2000, edited by Quintard Taylor and Shirley Ann Wilson Moore (University of Oklahoma Press 2003).