Colorado artist Grace Kennison paints her way into the reality of the West, a place layered thick with fictional narratives, mythical characters, suppressed histories, and surreal storylines.

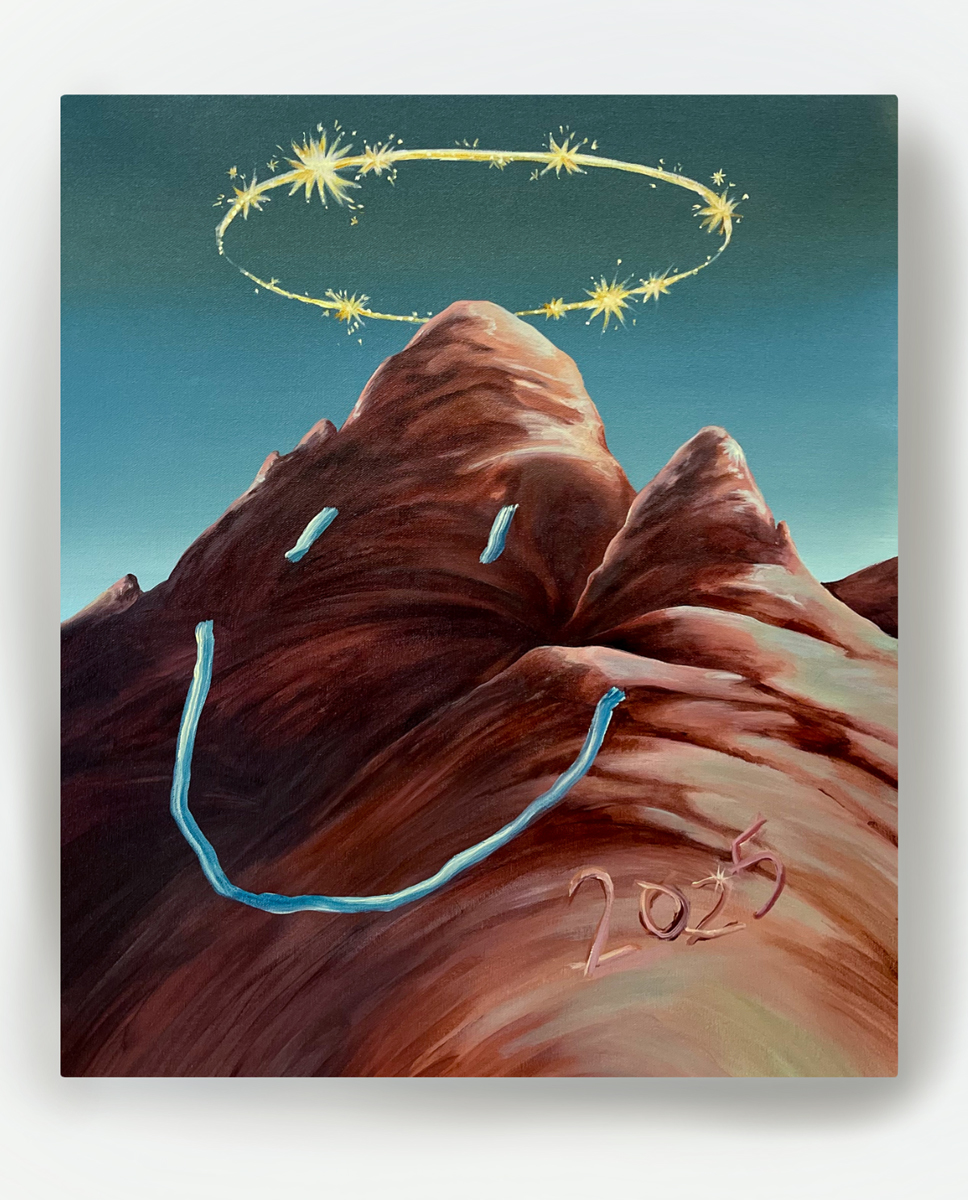

This article is part of our The Hyperlocal series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 11. Grace Kennison’s I Remember Being Alone, pictured in a process shot below, appears on the issue’s cover.

At the edge of Ridgway, Colorado, there’s a plot of land that locals call “tiny town.” It’s set up like a Western main street in miniature — a tiny church, a tiny bank, a tiny hotel, and a large teepee, perched on the banks of the Uncompahgre River.

Ridgway is full of these false fronts and Old West facades. Parts of the 1969 John Wayne flick True Grit were filmed two blocks away from the mini main street, and the town never fully took off its costumes.

So if you want a clean story about a 19th-century frontier town, Ridgway will deliver it; just don’t look too closely.

Look too closely and you’ll see the rows of empty shop fronts leading to a bustling coffee shop; a busted-down wood-paneled house next to a landscaper selling six-figure shrubs to second-home owners in Telluride. Look closely and you’ll see the river and the rodeo grounds, historical ranches cozied up to brand-new artist housing; people passing through and others just trying to get by; look too closely and you’ll see the American West, 2025.

In the middle of this movie set and myth-making maelstrom is the artist, Grace Kennison, her partner, Dylan, and their chihuahua, Blade.

Kennison landed in the southwest corner of the state during the summer of 2020, invited by Dylan to stay at his family cabin in Ouray, an old mining town about twenty minutes up the road from Ridgway. The cabin is perched above the confluence of three streams: Green Creek, Box Creek, and the Uncompahgre.

“Do you want to see the piece that I did when Dylan invited me out to the cabin?” Kennison asks, disappearing into the bedroom of their apartment-slash-studio. She returns to the kitchen with a fury of color, a surreal and wild painting of a woman devouring a fire devouring a barn.

I just had all this built up energy inside of me, figure was a way to see myself mirrored in a thing.

“It feels really sweet,” Kennison says, gazing at the early painting. “It belongs to a different version of me, for sure, that I have to take care of now, it meant a lot to her.”

Kennison grew up in Windsor, a northern Colorado town on the westernmost edge of the hazy Eastern Plains.

After college, she worked at a soap factory and painted on the side—mostly figures, which she’d become comfortable with while pursuing her degree in drawing with a minor in women’s studies.

“It was a very embodied time,” Kennison says of her college years, which she spent in nearby Fort Collins. “I just had all this built up energy inside of me, figure was a way to see myself mirrored in a thing. At a certain point, though, I just got sick of it.”

She was invited by Ari Meyers, curator at The Valley in Taos, to display work in a two-person show, with the caveat that she couldn’t paint figures.

First she had a meltdown. Then she “weaned off of figures by just painting hands,” Kennison says. That led to a breakthrough. “There was just this whole world,” she says. “Something got out of the way for me, where I was actually able to talk about what I wanted to talk about.”

What she wanted to talk about was her relationship to a new place. The Valley pieces were the first paintings she created after moving to Ridgway. “So I kind of left figure on the Front Range,” she says.

And that “whole world” she entered was populated by people like Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, Surrealist painters and writers who were close friends.

Kennison places a copy of Varos’s Letters, Dreams & Other Writings on the table. Varos is known for her paintings, but her writings are “fucking wack,” Kennison says. “They’re all over the place. I was led into a world of things that don’t totally track.”

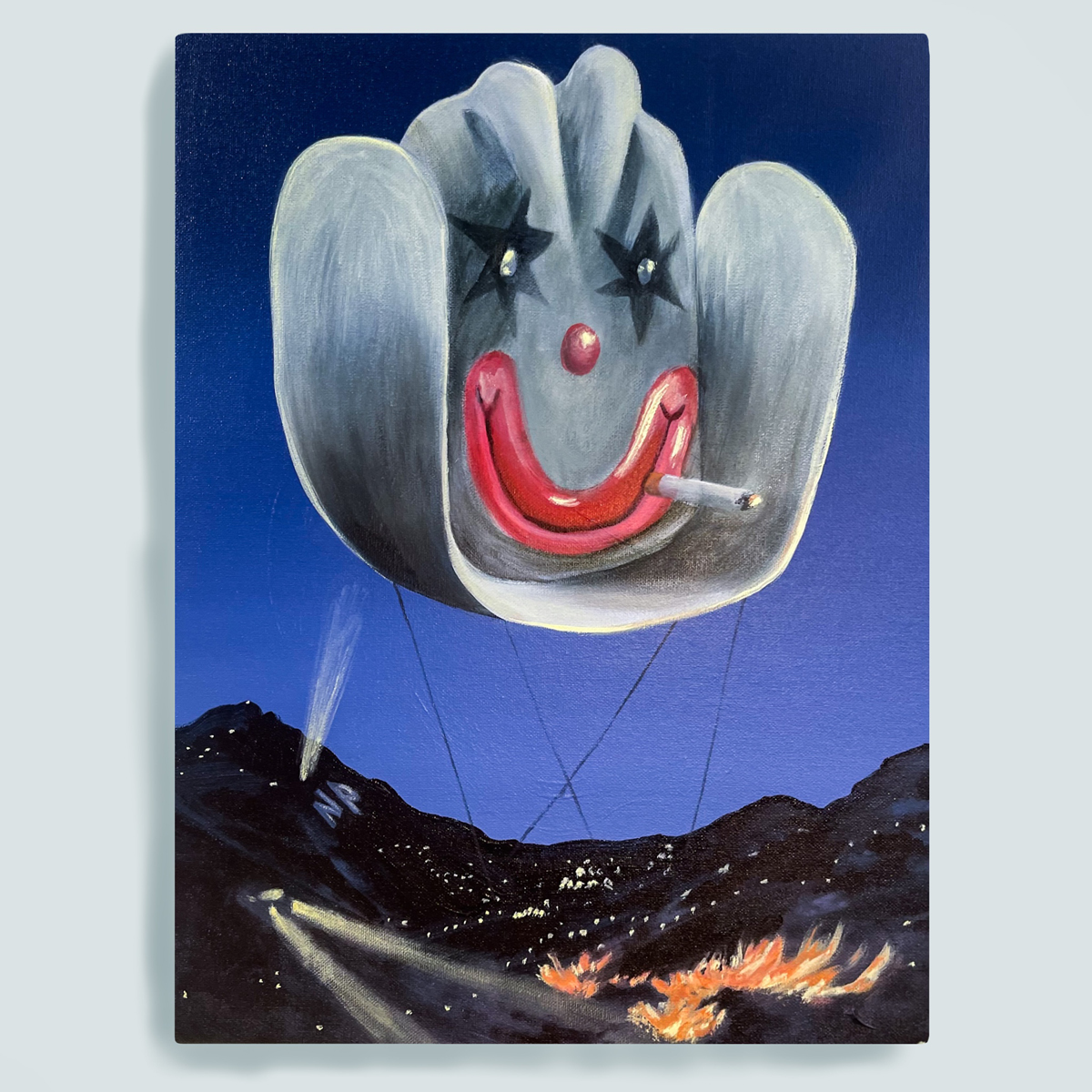

Kennison spent the past few months cranking out a series for a solo show called American Cowboy: Alternative Landscapes at the Masur Museum of Art in Louisiana (on view through August 1). When I visit, she’s got a half dozen of the paintings ready to go, and another half-dozen rolled up behind a desk, her trials and errors. Pinned to the wall is a partially finished piece: a mountain, a lake, an oil well.

“This one is just crushing me,” she says, pointing at the work in progress. “But I’m going to figure it out.”

The new series is a surreal mix of landscape and figure—mountains with mouths, babes that become winds, lands the color of sand and skin. She’s reintroducing the figure, but in a way that doesn’t demand a storyline, carefully skirting the viewer’s inclination to latch onto a main character, pulling focus to a wider context.

The way that I think about time out here, and the land—the narrative is so muddied.

“The thing I’d been told early on was that my paintings are very narrative,” Kennison says. “And I don’t know if I really rock with that.” Once she ditched the figures, the easy narratives started to dissolve, too.

“Maybe I can talk about what I’ve learned about the West and what it’s like being here — like why is this town the way it is, what is sacred here, what’s sacred to the people that took over?” she says. “I don’t know, it was just a process of trusting that I was implied in making the paintings.”

Like her figures, images of the West will always reappear, for better and worse. Kennison’s work, and Ridgway itself, play with those images like toys, recalibrating the John Wayne West to the role of a tiny town; a curious relic, a site to indulge in suspended disbelief.

“The way that I think about time out here, and the land—the narrative is so muddied. It’s not linear,” Kennison says. “Finding the truth of a place is way harder than any one story can offer you.”

Editor’s note: This article was made possible in part by a Rabkin Foundation travel writing grant.