Daniel McCoy Jr.’s father was an Irish biker and his mother a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Tribe of Oklahoma. His paintings bear influences from both sides, the aesthetic of psychedelic counterculture melding easily with the modernist flat style of mid-century Native painters like Fred Kabotie and Woody Crumbo. The day we met, he reverently pulled out examples of his father’s drawings on old paper bags from many decades past.

There were images of cars, one still life, and a couple of self-portraits. In the self-portraits, Daniel McCoy Sr. pictures himself riding a Harley (he was once a member of Hell’s Angels) in concentric haloes of fluorescent color among beasts you might see in the movie Dune.

The campy color palette and frenetic, wavy line-work that the younger McCoy (Citizen Potawatomi Nation) perfected easily lend to comic, even ironic, meditations on everything from Aristotle’s Great Chain of Being, to Allsup’s famed hot sauce. Pop culture, Americana, punk rock—it’s all there. His experiences vary just as widely, and each, it seems, comes into play in his paintings, including a stint as a sign painter. All are entry points for stories. And when McCoy starts chopping it up, there’s always a bit of self-deprecating humor in the mix.

Alicia Inez Guzmán: Who first motivated you to leave Bristow, Oklahoma, and come to Santa Fe?

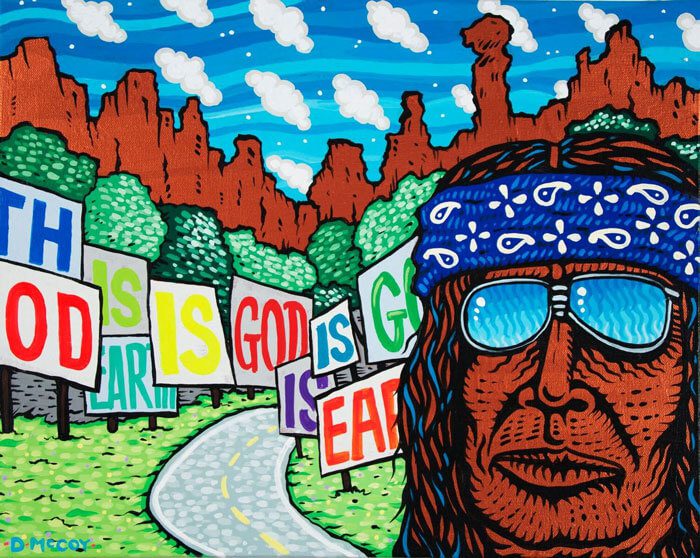

Daniel McCoy Jr.: Bob, this cool looking Native man, who fought in Vietnam, wore aviators, and was my mom’s age—he was the one who told me to go out West. He would talk about artists who went to Santa Fe to start their art careers. He had a lot of class. Bob would pull up in a big, white Cadillac that nobody knew where he got. He’d have a white suit on and listen to soul music and rhythm-and-blues records. He was an older, cooler uncle-type, who hung out with the kids and told tall tales. At ceremonial dances, we sat under the same arbor, and he’d tell us jokes to keep us awake all night. He would suggest that I should get out and see the world, because he liked my work and not many others did back then, when I started painting at fourteen or fifteen. Most people just wanted me to draw them tattoo designs!

Ten or fifteen years later, after I had become a commercial artist, he said, “I told you so.” Shortly after that, he died. But he was that character, a hero that keeps living on in my “Bob” paintings. By having him come back, he is iconic of following whatever direction calls.

AIG: What was your experience of going to the Institute of American Indian Arts?

I started back in ’93 and went to all three campuses over the years. When I first went, I had come from a boarding school that was very similar to the campus that was then located at the Santa Fe Indian School. The campus that was located at the College of Santa Fe felt different—it was alive. There was so much expression. Before, I was taught to paint in a traditional, old-school style in Oklahoma. But Santa Fe wasn’t into that. There was lots of activism back then. It was the four hundred year mark of Columbus in the Americas, and there was a certain kind of American Indian Movement (AIM) echo in response. That was my first eye-opener.

I was the youngest student at IAIA back then, only seventeen. But the age spectrum was so diverse, from seventeen to seventy. I was just beginning as an artist, and, when it came to critiques, my subject matter was pretty immature at the time. And some of the professors were kind of rough on me. But it was enough for me to go, “I’m gonna show them up.” It put a sense of dedication in me, but then I had to leave early to raise my son, who had just been born. I was a commercial sign painter for seven years, and then went back to IAIA at twenty-five. That was the second time.

I still think about the IAIA painters I met the first time I was there. They were all over the place creatively and absolutely inspiring to me.

The last time—the third time—I went to IAIA, I went to get more of a museum-studies background and to help my son who had grown up and was also attending. But then he ditched me! [laughs] Like the previous two times, I met a lot of students. I still think about the IAIA painters I met the first time I was there. They were all over the place creatively and absolutely inspiring to me. That influence is still present twenty-seven years later.

My kids are a big influence for me now. I dream of us all having group shows together.

Clayton Porter: Did sign painting influence your work?

Yes. At age eighteen, I had achieved my dream. I was an artist, a sign painter, by day, and I played in a punk rock band by night. Most sign painters are actually frustrated musicians. I was painting alongside working-class guys. That’s where the lettering in my work comes in. I love lettering, like the Thunderbird font. I was also really into death metal lettering and would make these advertising signs using it. Things changed during those years I was painting, from hand painting to digital and vinyl, and then the work dried up.

I wanted to go back to something organic and imperfect. That’s when I got into cartooning, a style that nobody was into at the time. Native art was still dominated by realism.

The billboard business taught me ultra-realism, which, when I went back to IAIA at twenty-five, I was tired of. I wanted to go back to something organic and imperfect. That’s when I got into cartooning, a style that nobody was into at the time. Native art was still dominated by realism. I was able to do things at IAIA that had a sense of humor that didn’t romanticize or have to tell a grim story. I was looking to move beyond that, to combine my colors with pop culture, with album covers, with everything. Now I’m adding realism back into my work—slowly.

CP: What’s the process of painting like? Do paintings always take a long time?

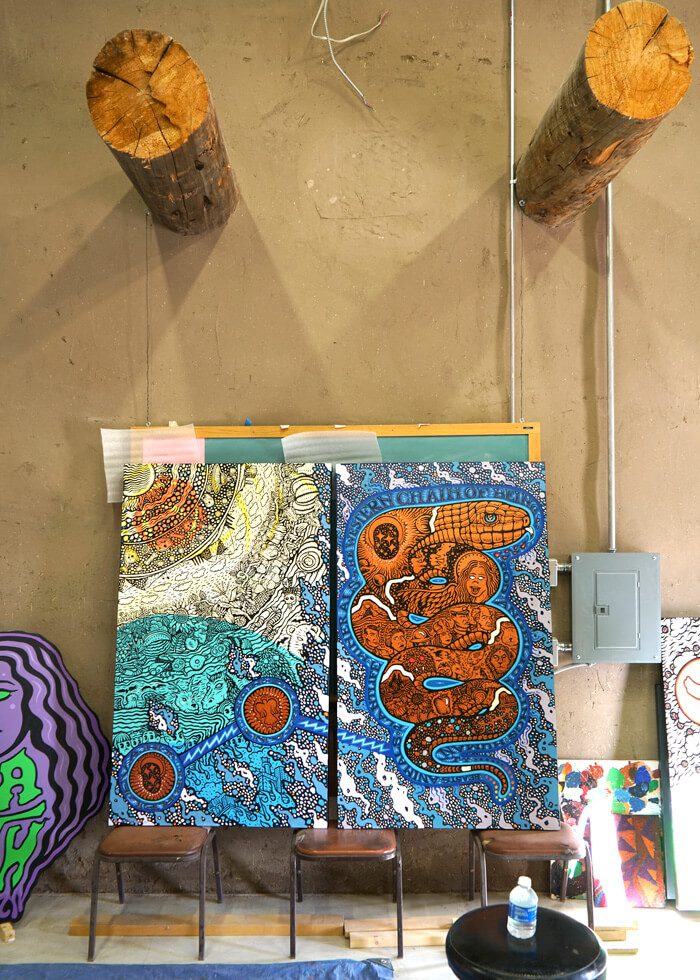

I’m having my first show in Oklahoma in thirteen years. And it’s kind of strange. There used to be this frenetic pressure to get things done quicker, to paint quicker. Now I don’t feel that way at all. There is a sense of timelessness in the painting. When you’re telling a story, sometimes it has to slowly unfold. I have discussions all the time with my wife, Topaz—for example with the painting The Chain of Being, based on Aristotle’s concept. It’s a hierarchy where you have God at the top, then angelic beings, people, animals, plants, rocks and minerals, in that order, which I painted in the body of a copperhead snake. But what if we have that all wrong? I’d been thinking about making this painting for years. It had to ferment, in a way. And then I painted the whole thing in two weeks, from the day I started. It’s a diptych that has the inverse of the hierarchy on the left side, with rocks and minerals—the earth—at the very top.

AIG: Can you talk about your character Hot Sauce Man?

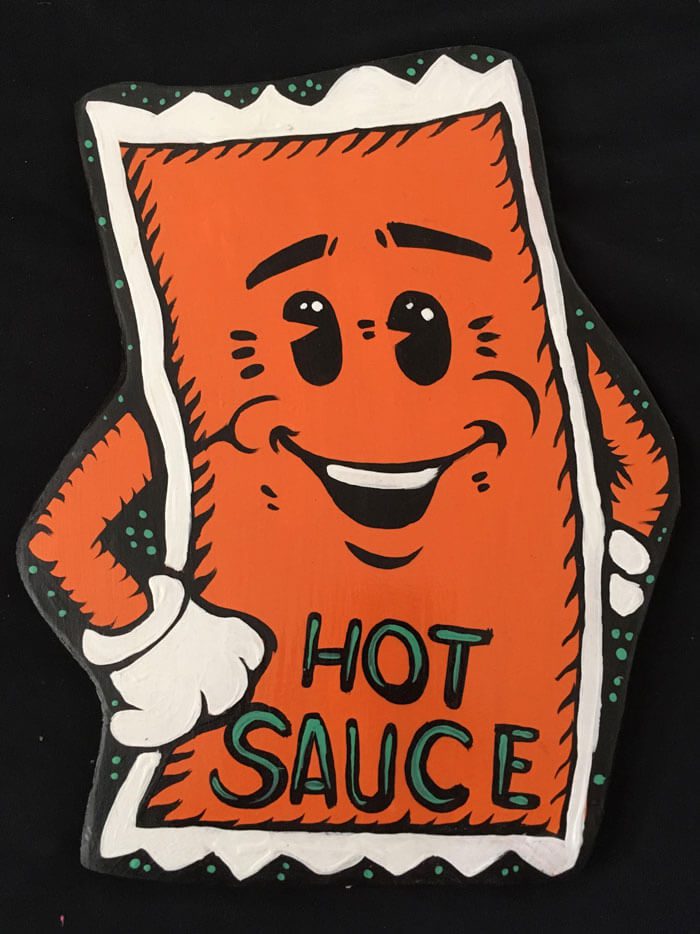

I think Allsup’s are culture hubs of New Mexico. I used to live off of Fifth Street and Quapaw near one. I loved their lettering and coloring scheme. And when I started researching, I found out they’re the largest publicly owned corporation in New Mexico. There was this one guy who must’ve gone to Allsup’s every night to buy a chimichanga. And he’d rip open the hot sauce and then throw the empty packets in my yard. There was this huge pile of hot sauce that was impossible to rake up, along with shooters of Yukon Jack. I started imagining the character of Hot Sauce Man as a stand-in for the people I used to see at Allsup’s—the gunfighter, the guy who changed the tire for the old gangster, the person making the late-night run.

But I also love food logos, Americana. It comes from my background in sign painting. But it’s very New Mexican and very Santa Fean. And then I started making my own logos. The first one was in my printmaking class with Jamison Chas Banks. That was my EARTH logo and kind of went back to the metal logos. The first one I made was in India ink, with a brush. It ended up looking like my mom.

AIG: What have been the biggest challenges of being an artist in Santa Fe?

I am not from a privileged background; I am not a lineage artist. I am a parent of four children: three live here in Santa Fe, and the oldest is on his own but still needs my help. I work in the art business for various museums and galleries; I work as an artist’s assistant and then have my own small business to support my family by myself. This is very educational. I love it, but the unpredictability of the day-to-day, month-to-month stress is my biggest challenge. I have endured all types of temper tantrums, “make it or break it” ultimatums, and jealousy by working in this field over the past twenty-eight years. It is exhausting—and heartbreaking. Sometimes it leads to isolation.

I have a studio and small house full of supplies, instruments, and tools to satisfy every idea that any artist could have. My new ideas flow through my mind endlessly, so creativity isn’t necessarily an issue. I feel at this point I could approach just about any venue and my work would be accepted. It’s the stress of balancing the societal daily needs and still being able to deliver the goods, not only to my employers but to my clients who believe in and collect my art. I find that this stress could potentially affect the line quality of my mark-making or integrity of the completed individual piece. I am looking forward to pulling back from this struggle one day, and hopefully this move will help mature and improve the overall quality and aesthetic of the work to come.