Celia Álvarez Muñoz’s first career retrospective at MCASD presents a rich body of work by the celebrated Arlington, Texas-based artist, who is committed to the complexity of stories from the U.S.-Mexico border.

If you’re like me, you witness nearly all of the world’s breaking news through a tiny digital news portal called a “smartphone.” Because of this, the war in Ukraine is enraging but, geographically, far off. Your life is touched by systemic racism, in one way or another, but most critical issues facing marginalized communities today—including but not limited to crises at the United States-Mexico border—don’t actively affect you.

Not so for Celia Álvarez Muñoz. Born and raised blocks from the downtown areas of El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, the tension between the U.S. and its neighbors consumed Álvarez Muñoz’s world throughout the developmental years of her life. Though she has traveled far and wide throughout her prolific career as a mixed-media conceptual artist and photographer, a vast majority of her work returns to her home on the border.

In March 2023, the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego opened Celia Álvarez Muñoz: Breaking the Binding, the first career retrospective for the Arlington, Texas-based artist. The exhibition brings together the massive, site-specific installations, photographic series, and book projects that have established her as the boundary-pushing artist we now know her to be. By way of humor, cultural symbolism, and rich, often lyrical storytelling, each of the selected pieces of Álvarez Muñoz’s work sheds light on the extensive stretch of land that straddles the border separating the U.S. and Mexico, as well as the bilingual and bicultural people who inhabit that land.

“Once, I thought that being a Catholic Chicana from El Paso were three strikes against me,” Álvarez Muñoz told the Los Angeles Times in 1991. “Now, that is precisely where I draw my material.”

The first work that greets Breaking the Binding viewers, El Limite (1991)—initially included in Álvarez Muñoz’s 1991 solo exhibition at MCASD—begins to peel back the layers of complexity that define Álvarez Muñoz’s experience.

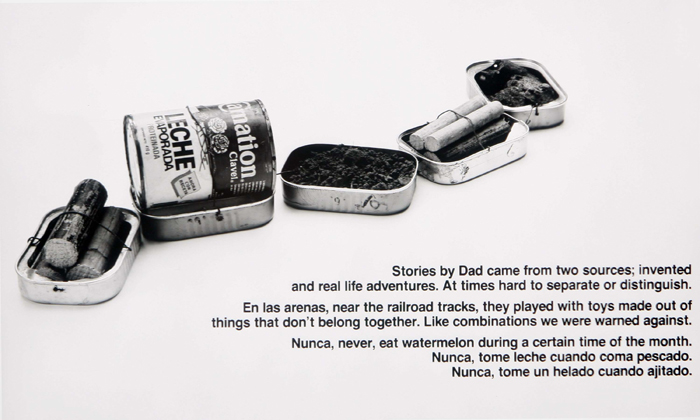

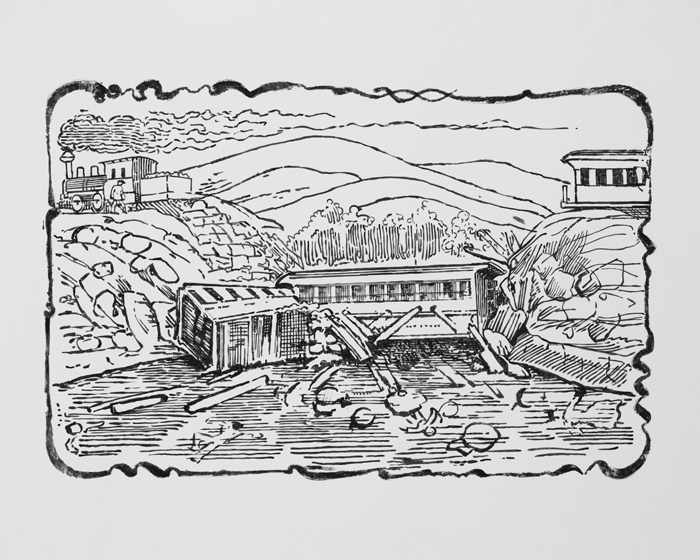

“Stories by Dad came from two sources; invented and real-life adventures. At times hard to separate or distinguish,” reads one stanza, referencing her father’s train-hopping youth. Next to the text, a black-and-white photograph of a sardine-can train trudges forward, carrying cargo like a can of Carnation evaporated milk and a small lump of dirt. “Some stories stemmed from trips to the Golden State on trains he jumped on in El Paso, during the Depression years. My favorite stories dealt with the war when he was moved across the world and throughout Europe, again, mostly by train.”

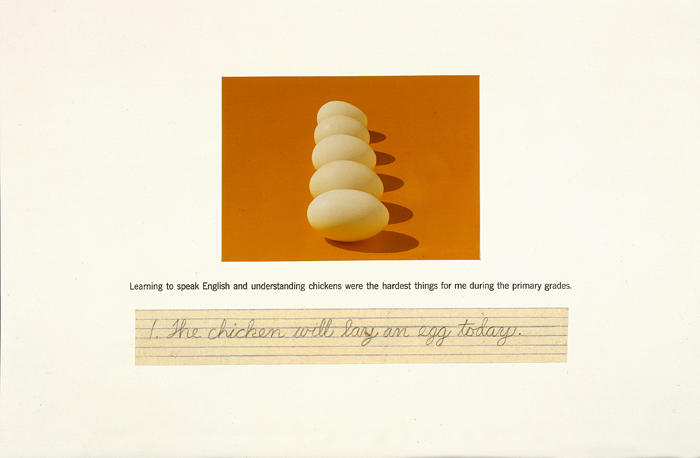

This combination of photography and text, both of which draw on Álvarez Muñoz’s personal history, became a staple of her work over the years. While the gallery floors of Breaking the Binding are crowded with glass cases and floor-to-ceiling installation pieces, the walls seem to be dedicated to Álvarez Muñoz’s intimately autobiographical work. Walking through the exhibition feels like wandering through the pages of the artist’s journal.

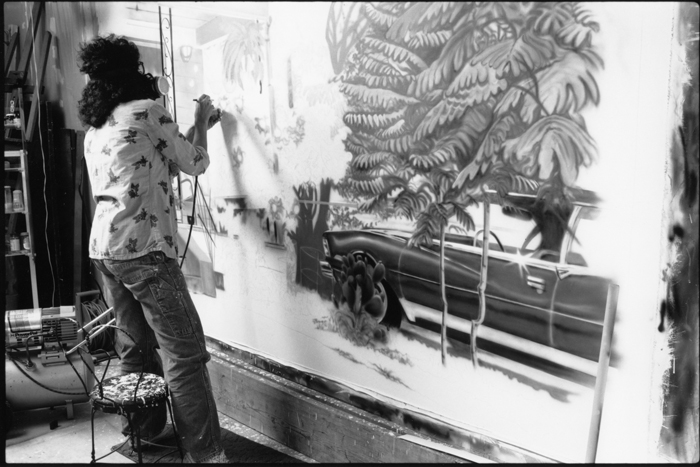

On paper, a biography of Álvarez Muñoz will tell you she was first introduced to conceptual art while working on her MFA at North Texas State University in Denton (now University of North Texas) in 1977, where she studied under multimedia artists like Vernon Fisher and abstract, conceptual artists such as Al Souza. Exploring each of the works on view in Breaking the Binding, however, will show you Álvarez Muñoz’s work as a binding-breaking artist began long before that.

For years, Álvarez Muñoz operated outside of the proverbial art world. After graduating from Texas Western University (now the University of Texas at El Paso) as an undergraduate, she worked as a fashion illustrator at a local department store. Later, she taught art classes for children. It wasn’t until she turned forty-two that Álvarez Muñoz pursued her own distinctive art practice.

Four years after finishing her MFA, she began to exhibit narrative, photography-based multimedia work. But even then, each subsequent exhibition seemed to challenge the expectations her critics had set for her. While many of her peers in the early ’80s worked to define what about their distinctive practices set them apart, Álvarez Muñoz focused instead on her upbringing in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, drawing from the deep well of her and her community’s pasts and crafting each of her unique artworks around whatever she discovered.

The expansive and poignant Fibra y Furia (1996), for example—which combines towers of unfurled fabric, dangling from ceiling to floor in massive spires, with ghostly stacks of cut-off jean shorts—was originally commissioned and exhibited as Fibra at the Center for the Arts at Yerba Buena Gardens in San Francisco to criticize the fashion industry in the background of her youth in El Paso. But over the years, Álvarez Muñoz toyed with its meaning. When she installed the work at the Irving Arts Center in 1999, for example, Álvarez Muñoz altered the piece to address the serial killings of young women in Juarez, as Seth Combs observed for The San Diego Union-Tribune.

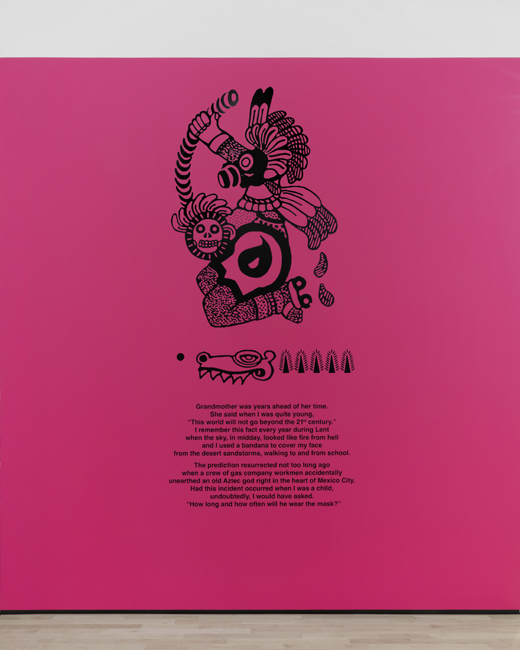

Petrocuatl (1988), an imaginary Aztec god with wiry red feathers shooting from its gas-mask head that Álvarez Muñoz created as a performance piece in 1981, was originally intended to critique the colonizing impulses buried beneath Western art history. In 1992, however, Álvarez Muñoz reimagined the work by installing the piece beside a framed National Geographic photograph of the ghost of Tenochtitlan’s pyramid, superimposed over present-day Mexico City, as part of “a contemporary reflection on the ancestral archives of Mexico in the flames of Spanish Conquest,” as Kate Green, PhD, wrote in an essay for the exhibition. Today, the image of the apocalypse-prepped god dreads our impending environmental collapse.

While the wider art world obsesses over fixing the meaning of a single work in order to cement its significance in a linear history of art, Álvarez Muñoz instead focuses on teasing out contradictions, leaning into uncomfortable truths, and, ultimately, invigorating conversation. I believe this is part of what has made both the relevance and the cultural impact of her work so lasting—she is not the kind of artist to step back and let her work speak for itself. Especially as the landscape of the debate over the borderlands has changed drastically, over the years, she has continued to change with it.

“It’s still evolving,” she told Combs about her work. “As long as it continues to feed and inform, I think that’s the job still. That’s the job I want.”

If anything is clear, it is that Álvarez Muñoz is a devout storyteller. And, like any good narrator, she knows the best stories are the ones that are colorful, clear-headed, and, perhaps most importantly, subject to change.

After the exhibition at MCASD closes in August, Celia Álvarez Muñoz: Breaking the Binding will travel to the University Art Museum at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, opening on October 20, 2023.