After five brain surgeries, Dallas-based Alicia Parham paints neurologically informed, otherworldly compositions in resilience.

This article is part of our OBSESSION series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 12.

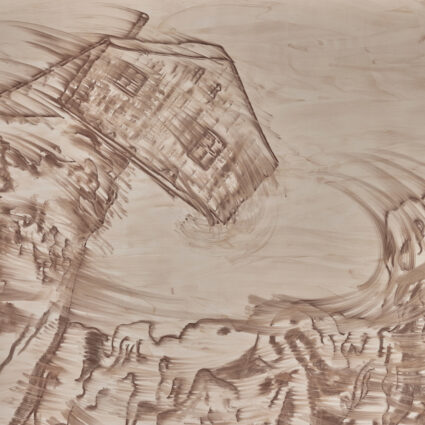

In 2021, Alicia Parham was an undergraduate painting and drawing major at the University of North Texas when she began to see things that weren’t there. Sometimes it was a field of color that would dance across the highway as she drove or a smudge of paint that had mistakenly made its way onto her canvas; but when she looked again, the plane of color had vanished entirely.

“I truly thought that I was going crazy or that I was haunted,” Parham tells me as we sit in her studio. She would soon find out, after a lengthy series of medical tests, that there was indeed a physical cause: a condition called pseudotumor cerebri. In Latin, this translates to “false brain tumor.” And the planes of color were (very real) eye or optical floaters, triggered by a swollen optical nerve caused by excessive fluid in her brain.

In 2022, Parham had five grueling brain surgeries, including three lumbar punctures and, ultimately, a brain implant. “Leading up to my fifth procedure I had about 75% blindness in my left eye. It was really creepy,” she recalls. “But it was in that moment, between my fourth and fifth procedure, that I felt compelled to paint in a way I hadn’t before.”

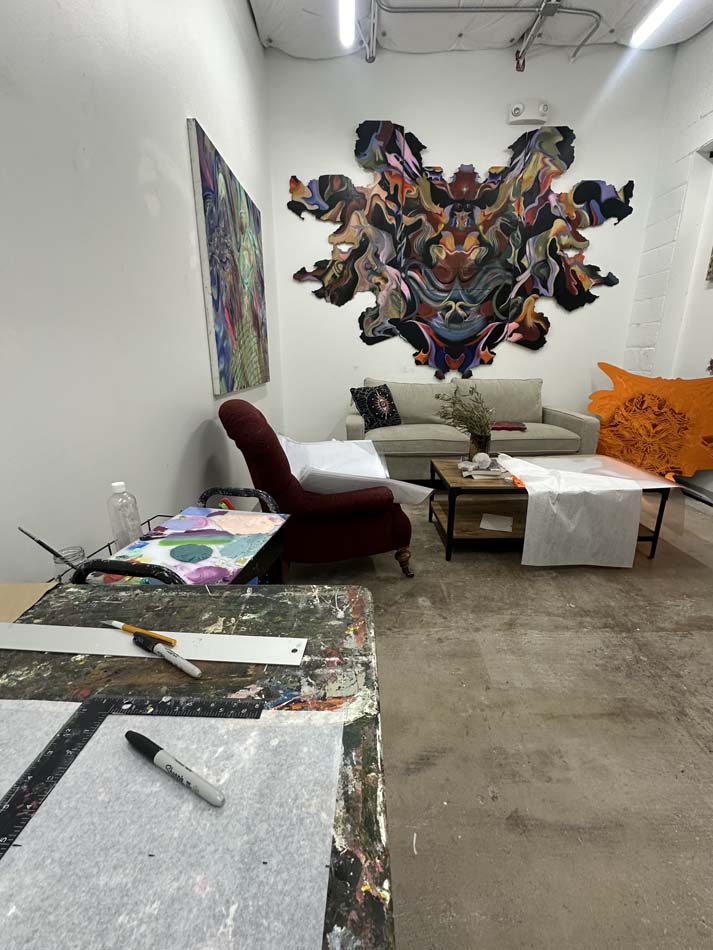

Prior to 2022, Parham’s artwork consisted of structured still life paintings, often depicting traditional elements like flowers and skeletons. But then, the shift happened. Her oil paintings became wholly abstract—psychedelic patterns and forms covering the surfaces of ambiguously shaped wooden panels that resemble Rorschach inkblots. Ribbons and splotches of color snake throughout each complex composition, forging a hypnotic rhythm. Each piece is as alien as it is familiar. She was painting her portrait. She was painting her brain.

“I had been playing with compositions in a software program called Touch Designer, but as I was translating these to a canvas and painting them, I was experiencing a lot of optical floaters,” the artist tells me. “I would see green paint in a place it shouldn’t have been but by the time I went to fix it, the green was gone. It was frustrating but I tried to lean into those frustrations and this next direction.”

Even her color palette changed as she became obsessed with how her perception of color was rapidly altering. Many of the optical floaters Parham experiences are in bright colors, like hot pink and neon green. So she swapped her typical palette of muted tones for a more fluorescent one.

This complete artistic shift coincided with her grief as she grappled with the long-term implications of this diagnosis, which include permanent eye damage and chronic migraines amongst other new realities. Parham’s practice underwent a metamorphosis as she became consumed with translating her bodily, lived experience into visuals.

In 2024, she received a grant from the Dallas Museum of Art and used the money to pay for an electroencephalogram (EEG) that is able to pull alpha, beta, delta, and gamma rays from live brain waves. She then exports the data into Touch Designer to manipulate the compositions, experimenting with different stimuli coming in.

It was in that moment, between my fourth and fifth procedure, that I felt compelled to paint in a way I hadn’t before.

“I did a few studies using the neurofeedback, one while reading a sad dog book that made me cry and another reading letters of recommendation from mentors that were really encouraging and validating,” Parham explains while pointing out smaller compositions that are mounted on her studio wall. The miniature shapes float around the larger panels like orbiting planets. “I like painting them together and displaying them in different ways to play with that idea of a spectrum of emotions coexisting together.”

Parham quickly found that every person has a unique spectrum of colors. She has hooked up the EEG to family members and friends, enamored with how varied the neurofeedback can look. She once ran the EEG on herself during the onset of a migraine, the outcome being a chaotic medley of vibrant fuchsias, deep magentas, and soft pastels. The resulting painting is titled Premonition (2024), highlighting a lesser-known migraine symptom: impending doom. This feeling of immense dread can precede a migraine (or other medical emergencies, like heart attacks or seizures), acting as an internal warning system for what is to come. Shortly after, Parham took her medicine and ran the EEG on herself again once the migraine had dissipated. Her brainwaves had transformed into an ocean of blues, remolding the aura on account of her more serene state of mind. The landscape of her brain was always evolving.

As she continues to navigate the physical and emotional challenges that accompany chronic illness and disability, Parham embraces these hardships with curiosity, wonder, and hope. Her multisensory, neurologically informed artwork is the fruit of her own resiliency and an intricate exploration into the human body and psyche.