In a single 1978 acquisition, the Museum of International Folk Art grew by 100,000 objects—and effectively adopted their fervent and eccentric collector.

This article is part of our OBSESSION series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 12.

SANTA FE—In 1978, when the Museum of International Folk Art decided to accept the Girard Foundation’s collection of over 100,000 miniatures, toys, masks, textiles, altarpieces, and dolls—along with dozens of other types of art and ephemera from around the globe—the curators involved couldn’t have known how all-consuming the process would become, nor how it would inform the rest of their careers.

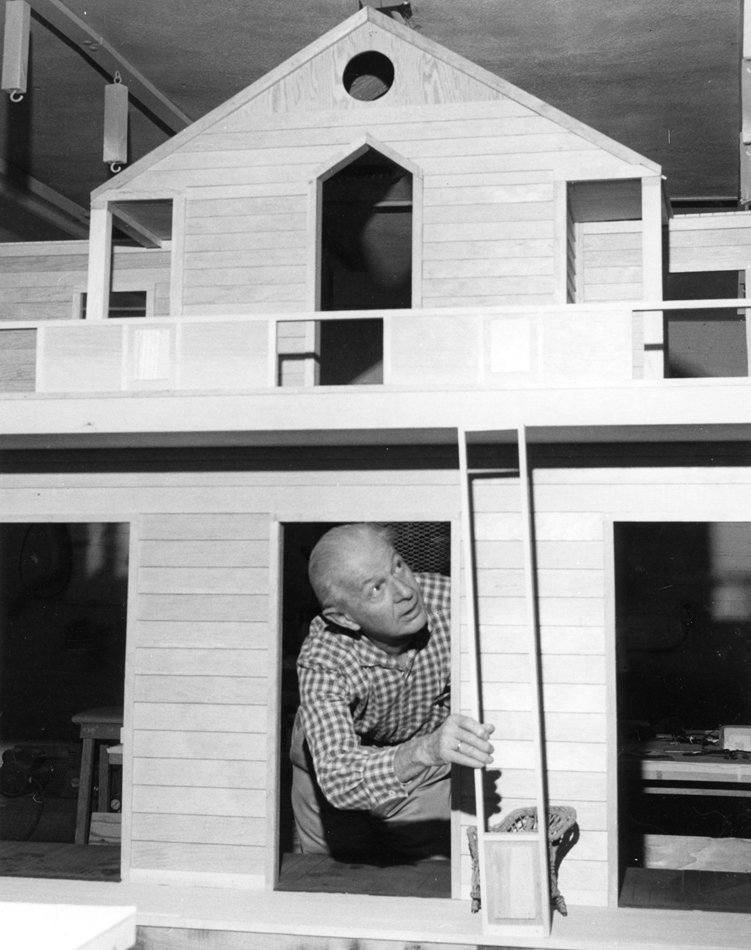

Led by then-director Yvonne Lange (who died in 2003) the small staff of mostly young women curators (plus a cadre of dedicated volunteers) spent years unpacking Alexander and Susan Girard’s treasures and arranging them in scenes, patterns, and vignettes according to his precise instructions. The work was both arduous and magical; Girard designed the exhibition as they went, determining the placement of items in the open gallery without a physical plan, mapping according to the internal legend in his brain.

Born in New York in 1907 and raised in Florence, Italy, Girard grew up steeped in Renaissance art and brought a maximalist’s sensibility to collecting and to his design aesthetic, which makes fun use of color and whimsy in textiles he designed for Herman Miller, like tightly grouped shapes in primary colors, or words, plants, and animals bent into patterns.

We had to figure out how to go from a collection of 10,000 objects to 100,000 objects with a skeletal staff.

Since its opening in 1981, more than a million people have visited his enduring masterwork in Santa Fe, the permanent exhibition Multiple Visions: A Common Bond. The sheer volume of objects displayed (over 10,000) overwhelms many visitors, but only a fraction of the collection is on view—about ninety percent of it lives downstairs in MOIFA’s stacks.

Author and curator Christine Mather was fresh out of graduate school and new to Santa Fe when she lucked into a job at MOIFA in 1976. “Any object that comes into a museum changes that museum,” she tells me from her folk art–packed home on Acequia Madre. “It’s like any child you have, it changes your life. A child of that size was both astounding and catastrophic, not necessarily in a negative way, but it was monumental… I didn’t totally embrace it at the time.”

Because the state legislature provided the funding to build the new Girard Wing, the entire collection needed to be inventoried and uploaded onto the state’s mainframe computer. “We had to figure out how to go from a collection of 10,000 objects to 100,000 objects with a skeletal staff who weren’t computer people,” Mather remembers. A group of over seventy volunteers helped to complete the cataloguing process by hand, which was then sent away for data entry, using a system that identifies and categorizes objects according to their functions.

“Girard was the first obsessive collector that I had any experience with,” says Charlene Cerny, the former interim director of MOIFA and cofounder and former executive director of International Folk Art Market. During the acquisition and installation of the collection, she served as everything from Girard’s daily chauffeur (he didn’t drive and went home for lunch) to the person appointed to remind him not to smoke in the galleries, to which Girard would often reply, “Oh, brother.”

The sheer volume of items in the collection dictated nearly four years of the curators’ professional lives. On a typical day during the installation process, “[Girard would] say, ‘I want to see everything from India on tables,’” Cerny explains. “So that’s like, a thousand trips in the elevator bringing up boxes. Then using the boxes as the building blocks of the design. It was all done organically.”

Cerny tells a story about how Sandro (a nickname both she and Mather use for Girard, though they say they only ever called him Mr. Girard to his face) once asked her to take him to K-Mart after work to check out the toy section; she describes his childlike glee in looking at the aisles of colorful objects, his enduring fascination with the emerging material world.

He recognized things are much more interesting in multiples. I always thought he was like a pyramid builder.

“What I took away from going to K-Mart is that I realized I carry blinders around with me all the time,” Cerny says. “I think it’s a rare person who doesn’t use categories to deal with the onslaught of sensory information that is life, but his categories were different. Part of his vision was superseding categories, like ‘tourist art’ or ‘airport art.’ He didn’t care if they were manufactured. He knew that they weren’t folk art, but he had a rebellious streak.”

In Mather’s words, Girard remains “the most famous American designer you’ve never heard of. One of the brilliant things about Girard was he recognized things are much more interesting in multiples. I always thought he was like a pyramid builder.” Though Girard himself said he didn’t see the connection, the influence of his collecting methods seems evident in his designs for Herman Miller, where he headed textile design in the 1950s, and where his work with color, pattern, and repeating motifs still feels contemporary and striking.

Likewise, Multiple Visions has achieved a sort of timelessness, solidifying—at forty-four years old—as a profound visual statement that does not privilege one viewer over another, but greets each visitor with riches. The magnitude of the exhibition is rewarded by repeat trips—both Mather and Cerny say they still find new objects in the collection, even now. It is a chronicle of one man’s design philosophy, a survey of nineteenth and twentieth century folk art, and it is an invitation to be curious. Girard wasn’t interested in controlling or even directing the viewer’s gaze, yet he manages to clearly channel his sensibilities via lifelong creative selection.

“It’s a mark of creative genius not to be held back by commonly held assumptions,” Cerny says. “Not to be punny, but Girard managed to maintain his own singular vision.”