Artist Douglas Miles (San Carlos Apache, Akimel O’odham) uses visual art and skateboard culture to amplify Indigenous voices.

Based on the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona, Douglas Miles (San Carlos Apache, Akimel O’odham) centers his own Indigenous community, using multiple media to counter stereotypes of Native life and culture while amplifying the voices of Native people, including family, friends, fellow artists, community members, and youth.

“My work captures Native reality, not romanticism,” explains Miles. “I’m focusing on triumph, not on tragedy.”

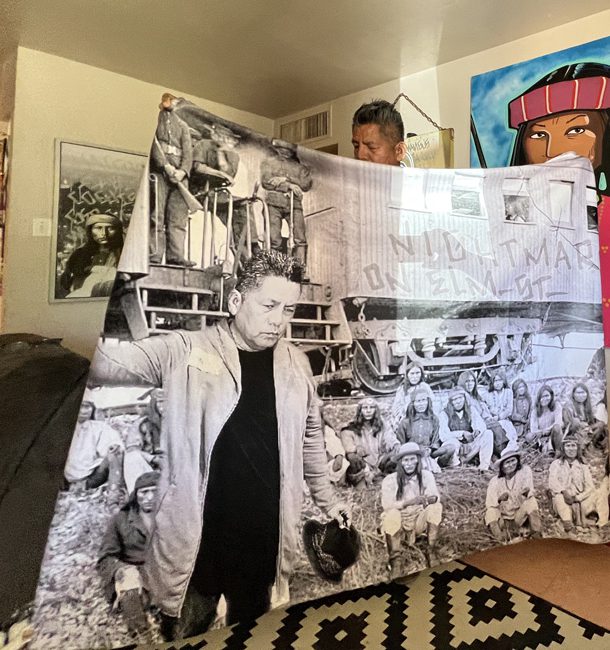

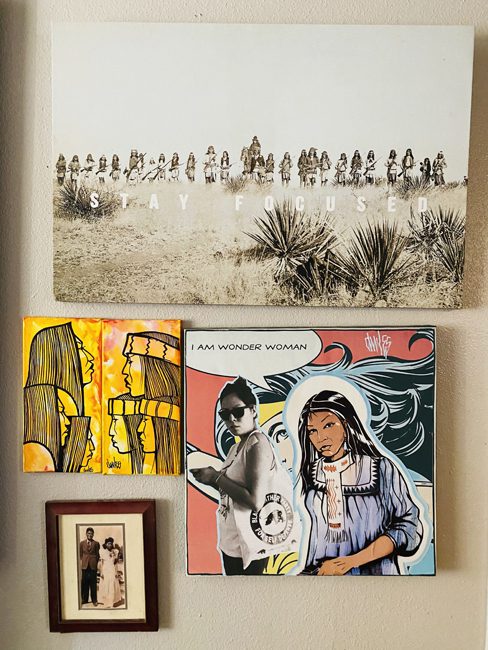

Miles lives in the T.C. Alley neighborhood of the San Carlos Apache Reservation, where his house also serves as his art studio. Typically, he works at the kitchen table or spreads out into the living room where the walls are primarily filled with his own artwork.

On one wall, there’s his portrait of the singer Sade painted on the top of a camping table, hinting at his love for music and the influence of pop culture on his work. Nearby there’s a painting of his father dressed in his military uniform. A portrait of his mother hangs in the hallway.

“It’s not really an ego thing,” he says. “I just don’t have a lot of space to store my art.”

It’s perfectly understandable, given that Miles has been building his body of work for several decades, creating not only murals and paintings on canvas or found objects, but also photographs, short films, designs for shoes and clothing, and more. “A lot of people don’t really get the fact that I work in so many mediums,” he says. “If I was white, they’d call me Picasso.”

Recently, he’s been working on an installation titled You’re Skating on Native Land, which is part of the Desert Rider exhibition that opened in late April 2022 and continues through September 18, 2022 at Phoenix Art Museum. The installation spans two white walls and includes several elements that are particularly characteristic of Miles’s work.

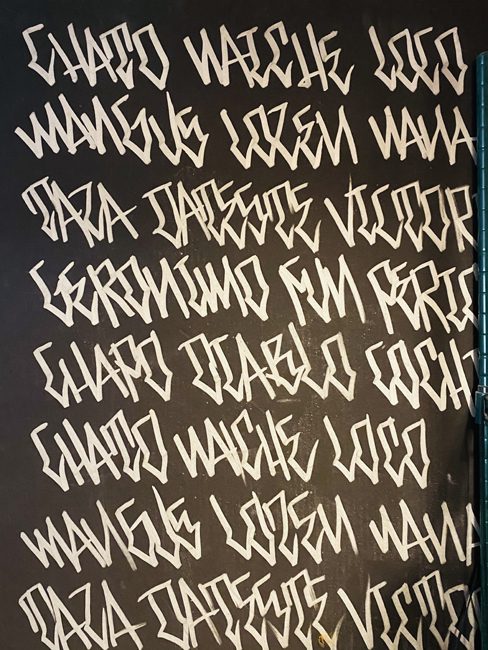

On one wall, he has painted five Native youth and a stylized Apache face surrounded by graffiti writing repeating the names of several Apache warriors and chiefs. On another, he’s mounted thirty identical skateboard decks with vinyl text reading “You’re Skating on Native Land,” flanked by a skull on the left and the image of five Native people on the right.

For Miles, skateboards are a vehicle for telling stories of Apache culture and experiences. In 2002, he founded Apache Skateboards, one of the country’s first Native-owned skateboard companies. In addition to making art and skate products, the business supports a youth skateboard crew in the San Carlos community where Miles and his son Douglas Miles, Jr. recently helped to bring a new skate park to life.

“Life is good on the reservation,” Miles says.

A studio visit with Miles isn’t complete without time spent exploring the San Carlos Indian Reservation that’s so integral to his identity and art practice. Hence our conversation included traveling between murals and skateboarding sites in the artist’s yellow vintage pickup truck, where a rustic gas container mounted behind the cab bears stenciled images of two Apache figures.

His largest mural to date is located on the reservation near the original skate park. The 2020 piece, commissioned by the non-profit One Arizona, includes several Apache figures and text encouraging people to vote. That same year he painted a mural reading “American Rent is Due” for the Painted Desert Project on the Navajo Nation. “That’s a way of saying that America needs to pay reparations,” he explains.

Miles was born and raised in Phoenix, where he has a strong creative presence.

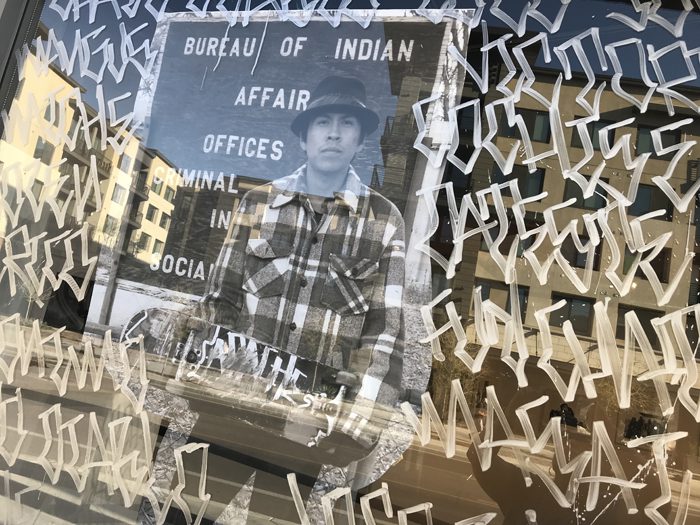

In 2019, the artist created an installation for his Everyday Sacred exhibition at Modified Arts gallery in downtown Phoenix, filling a street-facing wall of windows with life-size images of Apache people appearing to look out over the rampant development of an area dubbed the Roosevelt Row arts district.

In 2016, Miles and a small group of fellow artists painted the Let’s Get Free mural behind Bentley Gallery in Phoenix, depicting both the Apache warrior Geronimo and contemporary Indigenous people on a wall topped by barbed wire that suggests the histories of internment.

Here, as elsewhere, Miles brings attention to the people who first inhabited these lands and the contemporary experience of marginalization and displacement.

Miles’s art practice and cultural critique also extend into social media posts with imagery and text that call out misconceptions about Indigenous culture and contemporary life. Often his posts speak to the specificity of his own community while addressing issues impacting all Native tribes, such as land use, colonization, and boarding school trauma.

“The Apache people are still here,” he says. “We need to be telling our own stories.”