I Regret to Inform You: Rejected Public Art explores the process of applying to and proposing a public art project, while grappling with the ubiquity of rejection.

I Regret to Inform You: Rejected Public Art

June 6 – August 25, 2024

Arvada Center for the Arts and Humanities, Arvada, Colorado

In many regards, applying to public art projects can be a bit of a crapshoot. While previous professional experience, artworld notoriety, or particular identity markers can, no doubt, increase one’s chances of being selected for a project, the odds are never in one’s favor. With hundreds of applicants, a mere three to five finalists, and a single approved design, the expectations for success can never be too low.

I Regret to Inform You: Rejected Public Art, currently on view at the Arvada Center, focuses on “rejected public art proposals that were dreamed up by artist but were not selected to move forward.” While the exhibition includes several maquettes and original artist renderings, curator Collin Parson geared the exhibition more toward the dissemination of information via wall-mounted posters than highlighting aesthetic outputs. It runs in conjunction with the companion show inFORMed Space: Perspectives in Sculpture, an exhibition featuring large, free-standing sculptures by thirty-two Colorado artists (myself included) working in three-dimensions.

In the main, I Regret to Inform You attends to rejected proposals from over twenty Colorado-based artists—most of whom successfully received commissions for other public or public-facing art projects, such as Patrick Marold, Thomas “Detour” Evans, Jaime Molina, Joe Riché, and Susan Cooper. In addition to mock-ups of their proposed artworks, signage provides gallery attendees with a brief overview of each project, the artists’ synopses of their proposals, their thoughts and feelings regarding rejection, as well as their overall acceptance rate.

One of the biggest takeaways from I Regret to Inform You is the extreme difficulty of securing a public art project. Outside of a few outliers, most of the contributing artists boasted success rates below five percent when applying to Requests for Proposals (RFQ). In fact, the late Robert Lee Mangold—one of Denver’s most renowned modern sculptors, who exhibited internationally and produced a number of public artworks, including a piece at Denver’s Civic Center Park—had an acceptance rate of one percent.

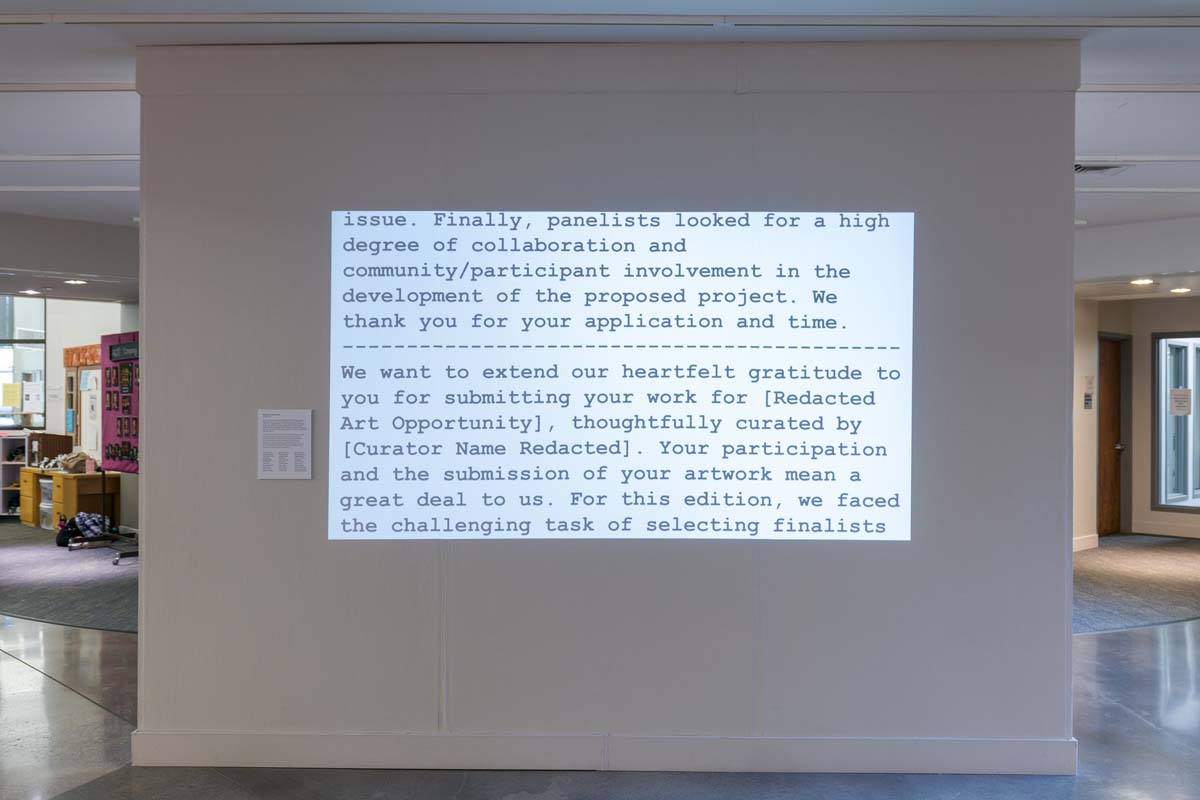

Further emphasizing the ubiquity of rejection and the rote formalism of non-acceptance is the five-minute Rejection Letter Video that’s projected against a wall near the exhibition’s entrance. Set against a white background, text in black courier font scrolls upward to the top of the projection’s throw. The text collages actual rejection letters from artists—one after the other—with identifying markers redacted. The video—set to loop—creates a pervasive sense of denial ad infinitum. Moreover, the staid, cookie-cutter language of the rejection letters fosters an inhuman, almost AI-generated refusal of an artist’s character, accomplishments, and self-worth. Sitting through the entire video and reading its text makes a viewer wonder how any artist could remain determined in the face of such demoralizing and banal verbiage.

While low acceptance rates, indeed, indicate the difficulty of securing a public art project, they also demonstrate how artists transform rejection into teachable moments for future advancement. For instance, artist Ramón Bonilla mentions that “rejection is always a possibility,” but it makes him “rethink and readjust the next steps…to sustain [his] art practice.” Similarly, Christine Nguyen notes that she “always learns something new” from these rejections, and Evans says that he “views this an opportunity to build relationships and practice pitching.”

I Regret to Inform You also clarifies the sense of community between public artists. Instead of cutthroat competition, those working in this field often express a sense of solidarity. Of her rejected proposal in downtown Denver, Nikki Pike says, “The final design that was chosen was designed by Kenzie Sitterud. I was excited to see the final chosen design and project: what an incredible sculpture!” Reminiscing on her rejected 1996 proposal for the city of Dallas, Susan Cooper recalls how she “met another artist, Wopo Holup, who also was rejected. We got to know each other and…were friends for many more years until her demise.” And Riché pragmatically notes that “there’s enough projects around for all of us to get some.”

Finally, viewers of the exhibition will be hard-pressed not to be impressed by the indefatigable resilience of these artists. “As a public artist,” Michael Clapper says, “one has to have a very thick skin, and has to develop the ability to move on fairly quickly…Even with all the rejections I’ve experienced as a public artist, the thrill of having been able to earn a living for over twenty-three years by creating thirty-seven public art projects around the country has certainly made it worthwhile.” And Mary Williams perhaps states it most concisely: “an artist faces a choice: succumb to defeat or persevere in their creative journey.” The artists in I Regret to Inform You have chosen, in the face of rejection, to persevere.

Update 7/23/24: In an earlier version of this story, Robert “Bob” Lee Mangold, a prominent Denver-based sculptor who passed away in 2023, was mistakenly identified as the minimalist sculptor Robert Mangold.