From James Turrell’s Roden Crater in Arizona to Charles Ross’s Star Axis in New Mexico and Robert Smithson’s Amarillo Ramp in Texas, some Southwest land art is stubbornly elusive.

Three years after artist Robert Smithson completed the monumental earthwork Spiral Jetty (1970) at Utah’s Great Salt Lake, he perished in a plane crash while surveying the site for his final work-in-progress from the sky, along with pilot Gale Ray Rogers and photographer Richard I. Curtin.

Today Smithson’s Amarillo Ramp (1973), a broken circle that originally rose from an artificial lake seventeen miles from the sculpture’s Texas namesake, still exists within the landscape. It’s one of many site-specific works in the Southwest that’s shrouded in mystery—and rarely seen.

Nancy Holt, along with fellow artists Tony Shafrazi and Richard Serra, posthumously completed the earthwork, which has been gradually eroding over time amid flourishing mesquite trees and the lakebed that’s now dry, manifesting Smithson’s own understanding of nature as collaborator.

“If you were to see it now, you would see an artwork that is a ruin of an artwork,” reflects Lisa Le Feuvre, executive director for the Holt/Smithson Foundation in Santa Fe (and a member of Southwest Contemporary‘s Community Editorial Advisory Board). She says that’s just what the artist intended, but also notes that the work is “looked after so it doesn’t disappear.”

Relatively few people experience Amarillo Ramp in person, in part because it’s located on a private working ranch. That means those wanting to see it have to make arrangements through the foundation—at least for now.

“Perhaps in the future that will change,” says Le Feuvre. “Perhaps there would be a moment where it would go into ownership where it’s easier to see it.”

Meanwhile, there’s another rarely seen artwork that’s located in West Texas, although it takes a vastly different physical form.

The Hill by James Magee, an outdoor art installation comprising four stone and steel buildings laid out in a cruciform pattern and the metal and mixed-media sculptures Magee placed inside them, was still a work in progress when the El Paso-based artist died in September 2024.

Magee worked on the project, which is located in the Chihuahuan Desert about seventy miles east of El Paso, for forty years. But the interior of the fourth building was never completed, and the artist has been quoted as saying any remaining work would end the day he died.

Today The Hill is managed by the Cornudas Mountain Foundation, which fields requests for private visits to the site. Citing support staff and travel costs, the organization asks that individuals pay $250 and couples pay $400 to tour The Hill. Only a dozen people can visit at one time.

In the case of Paolo Soleri’s Amphitheater, an outdoor performance space that opened in 1970 in Northern New Mexico, it isn’t cost that precludes a wide audience.

Instead, it’s the architectural artwork’s location—and the uncertainty surrounding the structure’s future.

Soleri’s 650-seat amphitheater was originally commissioned by the Institute of American Indian Arts, while it was housed at the Santa Fe Indian School where the work still stands today.

The school closed the amphitheater in 2010, after a final concert by Lyle Lovett. Others who’ve performed there include Leonard Cohen, Carlos Santana, and Stevie Ray Vaughan, by the way.

In recent years, Soleri’s performance space has been the subject of wide-ranging discussions, with some recommending demolition and others advocating preservation and/or restoration. Meanwhile, the city of Santa Fe and others are exploring building a performance venue at another site.

In the Eastern Plains of New Mexico, another mysterious artwork has been taking shape for nearly fifty years. Artist Charles Ross began developing Star Axis in 1971, and construction started in 1976 on what he calls an “architectonic earth/star sculpture constructed with the geometry of the stars.” Built from granite, sandstone, and other materials, the work explores “light, time, and planetary motion.”

The monumental work stands eleven stories high and 0.1 mile wide, and has five key components including a “Star Tunnel” aligned with the Earth’s axis and a “Solar Pyramid” that marks the movements of the Sun on a “Shadow Field.”

Ross is on target to complete the sculpture this year, according to a spokesperson for the Land Light Foundation that supports the project, who says Star Axis could open to the public as early as 2027.

That doesn’t mean it’s impossible to experience the work sooner, however. The foundation has several giving levels with perks that include time at the site. Those who donate $1,000 can bring a guest for a day trip to Star Axis between June and December, and the $10,000 giving level includes an overnight stay.

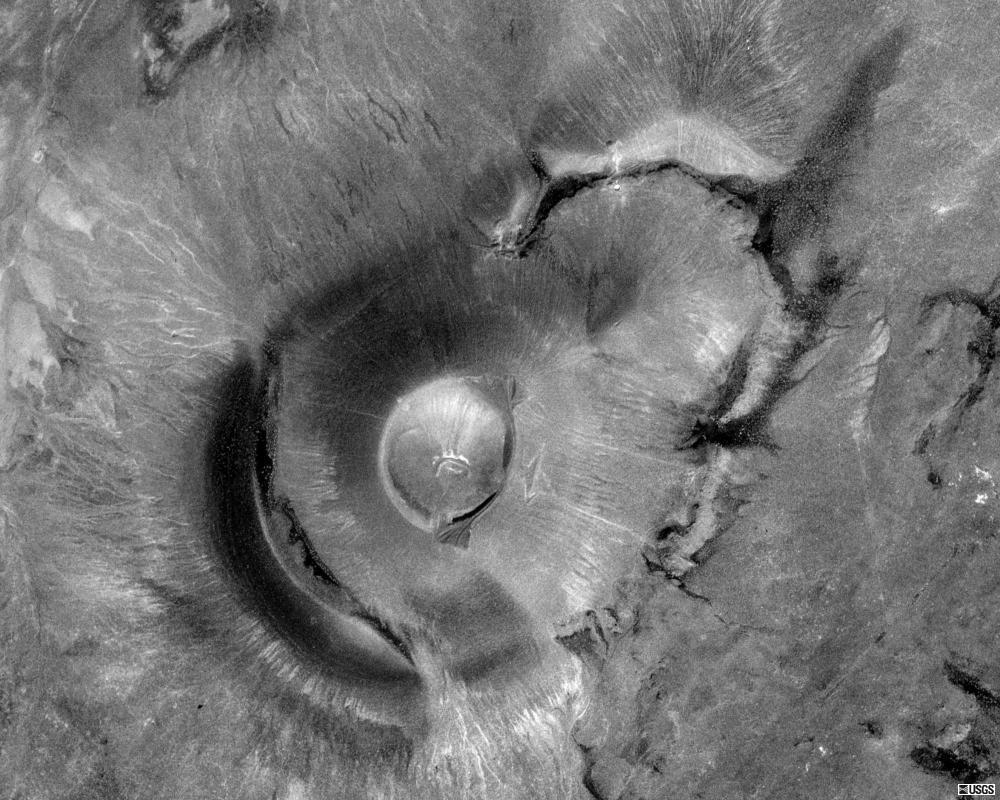

In the Painted Desert of Northern Arizona, an artist renowned for his work with light has spent more than five decades transforming a volcanic cinder cone into a large-scale artwork that includes myriad chambers, tunnels, and apertures that capture light.

James Turrell began designing Roden Crater in 1974, envisioning elements that include the “Fumarole Space,” which acts as both a radio telescope and camera obscura. He initiated construction in 1977.

Expected completion dates have come and gone, and the Skystone Foundation that supports the project hasn’t revealed an updated timeline for completion.

On some level, the rumors and mystery become a part of these artworks.

Foundation materials indicate that they’re working to raise $200 million for Turrell to fully realize the project. Along the way, famous visitors including Drake, Kanye West, Kim Kardashian, and NBA star Devin Booker have given the project greater visibility. West donated $10 million to the project in 2019.

Whether and how more people will have access to these large-scale artworks in the Southwest remains to be seen. Meanwhile, the speculation only fuels more interest from travelers and art lovers alike.

That’s okay with Lisa Le Feuvre of the Holt/Smithson Foundation, who has a compelling take on all the unknowns at play with Amarillo Ramp and other major earthworks. “On some level,” she says, “the rumors and mystery become a part of these artworks.”

Correction 08/15/2025: An earlier version of this article stated that Charles Ross began work on Star Axis in 1976. Ross began developing the project in 1971, with construction starting in 1976.