On an Artpace residency, New York-based artist Melissa Joseph fell in love with the “intertwined” community of San Antonio. The feeling is mutual.

SAN ANTONIO, TX—The multimedia artist Melissa Joseph creates works that poetically convey memory and history through an autobiographical lens. As part of the 2024 cohort of Artpace’s prestigious International Artist-in-Residence Program in San Antonio, she spent two months earlier this year in the city befriending the locals and scouring junkyards and flea markets across San Antonio to source the inspiration and materials for her culminating exhibition, A Wide Action is Not a Width, which she has called a “love letter to San Antonio.”

The title of the exhibition stems from Gertrude Stein’s classic book Tender Buttons (1914). Like the poetic work, in which the meaning of everyday words is disrupted as they are restructured unconventionally throughout the text, Joseph also seeks to give new meaning to the objects she repurposes. For the show’s centerpiece, for example, Joseph sourced a truck bed from a Pick-n-Pull scrapyard on the south side of the city and hauled it back to her Artpace studio, which—fittingly—was once an automobile showroom dating to the 1920s. The monumental work Texas Jali comprises a decommissioned 1989 Ford pickup truck bed, which has been toppled on its side and features needle felted paintings on side view mirrors Joseph affixed to the truck’s underside.

Like Texas Jali, most of the works Joseph produced for the exhibition have some conceptual connection to the city—which she had never previously visited—and her experience participating in the program. While there are self-referential moments in the body of work, those elements have been fused with the ethos of San Antonio, where “everyone and everything is intertwined,” Joseph tells me.

For example, the needle felted element within Texas Jali depicts her brother’s hand wearing a ring topped with a pink stone that her father was wearing when he died, which was lost for around a decade but resurfaced while Joseph was working in San Antonio.

Similarly, the truck bed’s custom-made headache rack (a protective frame mounted on the rearview window) evokes her Indian-American heritage, referencing both the ubiquitous geometric designs of India and the latticed ornamental screens traditional in Indian decor, called jali. The needle felt paintings in the rearview mirrors honor her fellow artists-in-residence, the Ghanaian artist Patrick Quarm and the San Antonio-based artist José Villalobos.

Joseph typically maintains a studio at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts in New York, producing works that amalgamate felt, ceramics, and found objects. Before she arrived in San Antonio, she had always worked on a smaller scale to accommodate her midtown Manhattan space—most works not exceeding six feet in height and certainly not incorporating car parts.

“Artists who work small are always told that we should make it bigger,” she says. “It was challenging to visualize exactly what I wanted to do in San Antonio before I got there because I wanted to respond to the history of the space, but I knew I wanted to work bigger because I don’t normally have that access. This was a chance to do something ambitious that couldn’t be done somewhere else.”

Nonetheless, the show features some smaller pieces, like Rigo and Ruben at Presa House, one of three needle felt paintings that depict the cultural community of San Antonio, which she framed with vintage ceramic pipes that once lined the San Antonio waterways. The ceramic pipes, which were replaced with more durable PVC starting in the 1960s, proved challenging to source, requiring a series of cold calls to vintage sellers, plumbers, and other connections in San Antonio. “The work became very much about that place and that time, and that was important to me,” Joseph says. “What was the point of making work there that I could have made in New York?”

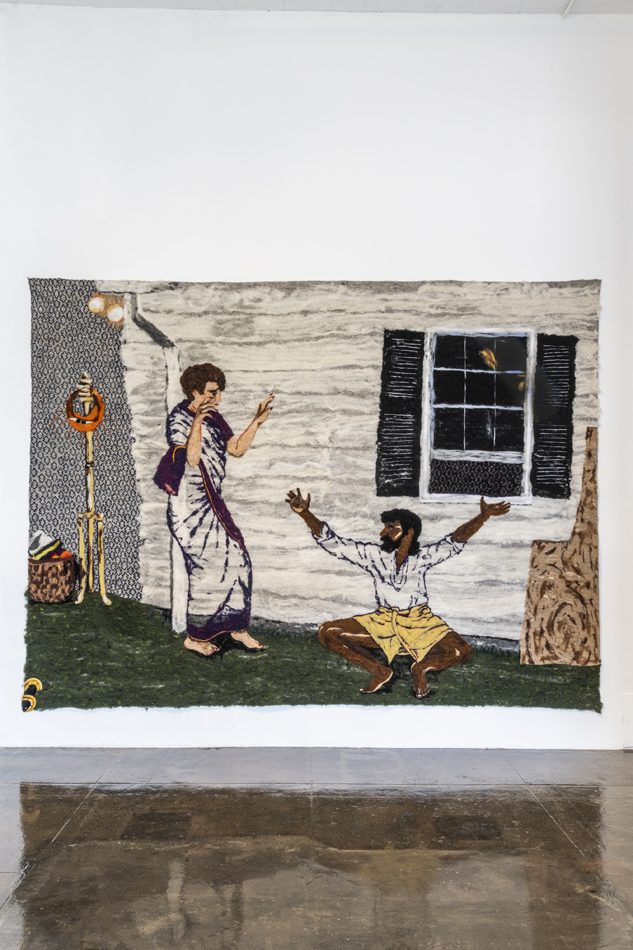

Joseph also completed her largest needle felt work in San Antonio, a nine-by-twelve-foot painting titled Indian Dirty Dancing that preserves the memory of her deceased parents, showing the couple dancing at an event in her hometown in Pennsylvania. “I remember them practicing for it when I was kid but I never saw the performance, then a photograph of it emerged in the last few years,” she says. “I have some questions around this event that I’ll never know the answer to.”

The program is expected to shrink in the coming years due to budget cuts, the impact of which could hold significant consequences for San Antonio’s art ecosystem.

She adds that the overarching message of the work is that “some things don’t have definitive answers and maybe never will,” and the concept of “the chase” is part of what the work aims to achieve. Indian Dirty Dancing, a powerful example of Joseph’s practice, has been acquired by Ruby City in downtown San Antonio, where it will be exhibited in the future. Meanwhile, Joseph is currently featured in We wake in the middle of a life, hungry at Rebecca Camacho Presents in San Francisco, on view through July 13, 2024.

The late artist and philanthropist Linda Pace, who founded and posthumously opened Ruby City in 2019, launched the Artpace artist-in-residence program in 1993. The program, which is now overseen by the Linda Pace Foundation, has welcomed artists like Maurizio Cattelan, Glenn Ligon, and Cauleen Smith in past iterations.

The 2024 cohort of the Artpace artist-in-residence program was selected by the Ghanaian-American curator Larry Ossei-Mensah. The artists received a $6,000 stipend, a $10,000 production budget, and other perks like a vehicle and an on-site apartment. But the program is expected to shrink in the coming years due to budget cuts, the impact of which could hold significant consequences for San Antonio’s art ecosystem.