Utah artist Andrew Alba’s newest series of stoic portraits, on display at Modern West starting later this month, come after years of dark brooding and artistic scuffles.

GLENDALE, UT—Painter Andrew Alba’s studio, just west of the Center Street bridge in Glendale, Utah, sits behind his home and over an obstacle course of children’s toys. Light pours in from the surrounding windows and the large, glass sliding door. The energy is inviting, playful, and comfortably chaotic.

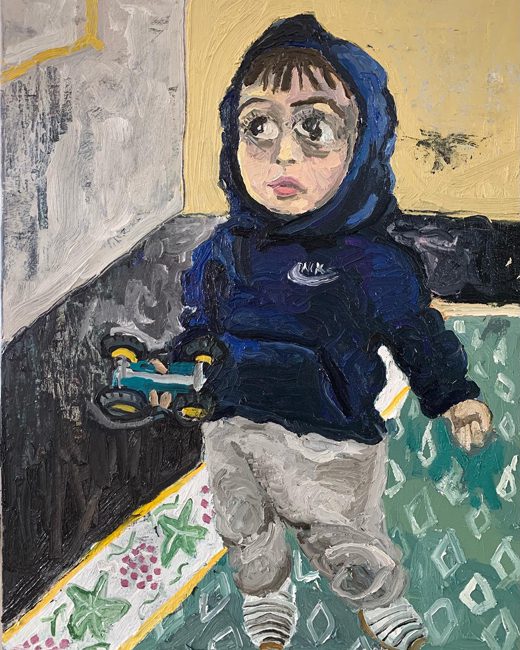

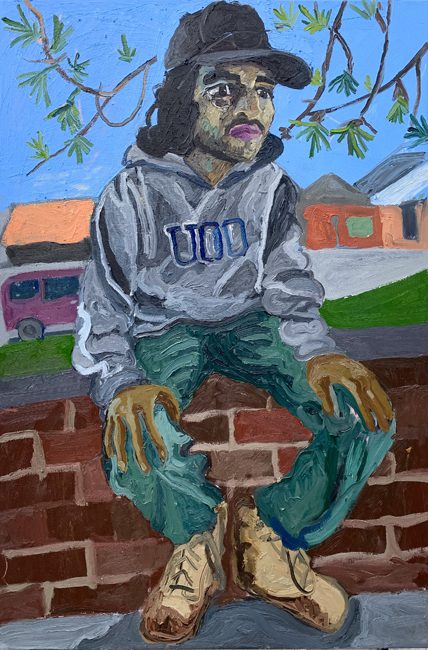

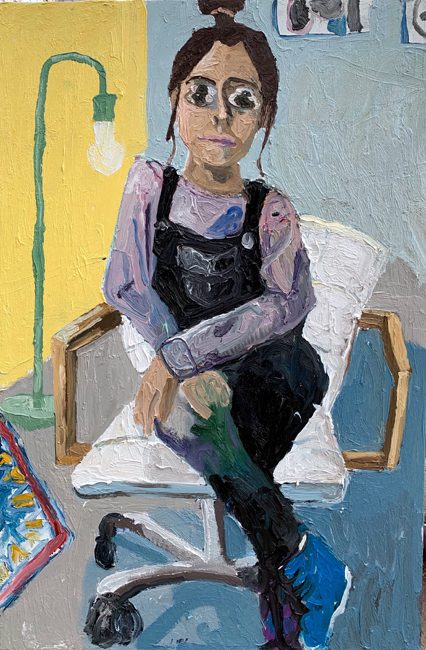

Pieces from his most recent series, You May Find Yourself, lean against the walls, as if gloating while they witness the creation of their siblings. The portrait collection feels like characters within Alba’s universe announcing their individual presence, as though you are sitting at the head of a boardroom within Alba’s mind, who has scratched and clawed to exhibit at some of Salt Lake City’s most prestigious museums and galleries.

As peaceful and stoic as these portraits seem, they come at the end of a long line of collections that have crept out of the darker spaces occupying Alba’s psyche.

Originally a musician in his early 20s, Alba never felt like his music conjured the pride and sense of accomplishment he was looking for. It wasn’t until Alba experienced a work-related injury as a welder, one that rendered him incapable of working or playing the guitar, that he discovered painting as a way to relieve the compounding and visceral pain he was experiencing.

“It was the type of depression that was very angry. I hated the world,” he says. “I really got into a very intense form of painting. That is where I got serious.”

While Alba was grieving his limitation, he discovered that the space between himself and the canvas was the only place where no one could tell him what to do. A born contrarian, Alba’s newfound feeling of autonomy launched him into his pursuit as a professional artist.

“Drawing in a realistic manner felt really boring to me,” he says. “When I got to this stage at [age] 24, it was really more about the poetics of painting and the magic of it.” This is when Alba chose to abandon his technical skills to follow his method of intuitive painting.

Alba’s sessions would become intense, unhinged, and he’d lose himself in his own movement. “Every stroke is very deliberate. I didn’t like feeling like an animal while I painted, but I think it was really important for me to learn that intuitive side of painting,” Alba says.

Alba’s desire to paint can only be described as carnal. His paintings breathe and bleed just as viciously as he does. The oil paint strokes are heavy and thick as raised grooves seemingly dig into the canvas like hands carving away at the ground. He paints “each stroke with a bullet.”

After eight years of rejection, Alba landed his first exhibition and residency through Salt Lake City’s Utah Museum of Contemporary Art in 2018 with his series Gas Station Honeydew. It was the first time he had a studio with air conditioning and heat, and he felt focused on his mission to disrupt the academic art landscape. Alba painted distorted portraits of brown characters with fruit and bandanas as lobes protruding from their faces.

His artist statement for Gas Station Honeydew read: “As a child of a Mexican-American father and a white mother, Alba’s work balances identity and representation by presenting brown people in white spaces.” Alba knew having the bodies of people of color taking up space at UMOCA would be part of his mission.

“As petty as it is, I want to prove people wrong. There’s not many brown, unacademic painters in the art world.” He felt the need to reappropriate his own brownness instead of pushing it away—as he had done in his youth—in order to create change. “It is about disruption. It’s about making people do a double take and proposing questions,” Alba says.

The year of Alba’s UMOCA residency marked the birth of his first child, Ariana, which felt like it “lit a fire under his ass,” and he had to pitch himself to galleries to survive. His exhibition Everyone Sucios at Salt Lake City’s Finch Lane Gallery in 2020 reached through Alba, back to where his work was originally rooted—the anger and darkness lurking within him.

“Everyone kept saying that the UMOCA show was a beautiful, colorful show, and with the Finch Lane show, I wanted to hit on the other side,” he says. His strategy was to limit his palette to dark colors and make the subject matter heavier. “I wanted it to feel more like a nightmare.”

As Alba now moves into a more consistent phase of his career, he has been pondering upon the trajectory of his work.

“Now that I’m not getting many rejections, I’m suspicious of my work. I think, ‘Am I not pushing it hard enough?’” While he currently plays around with the intentionality behind his work, the pendulum in Alba’s mind swings between making works with an impactful message and creating pieces that are not trying to say anything at all. “I don’t consider myself to be an activist,” he says. “I’m just an artist.”

There’s a taped-up piece of paper on the wall of his studio with bolded words reading, “Dead don’t paint.” Serving as a symbol of motivation, Alba considers this to mark one of many fleeting moments experienced in his studio.

“Sometimes I just write shit,” he says, letting go of the significance this message held at one point. This is his nature: feeling the potency of his emotion only long enough to streak its mark on the canvas. Alba’s work is built by these fragments of time—whether it is a moment of despair or the joy he feels when his kids paint alongside him, Alba holds on to these fragments just long enough to paint them, then lets them go.

Today, Alba is wrapping up a portrait series for a group exhibition at Salt Lake City’s Modern West (scheduled to take place May 20 through July 9, 2022) in his home surrounded by his partner Trish, Ariana, and his most recent creation, his son Diego. A collection that is, in his words, “more painterly,” his works in You May Find Yourself speaks to Alba’s brighter side, celebrating the characters in his life with lively and colorful representations. Alba’s next collection could be anything, but the only certain thing is that he will be breaking and disrupting something through it—it’ll be up to the viewer to decide what that is.

Alba believes that art can change the world and that art—good art—is about fragmenting ideas.

“I’m always trying to break something. I don’t know if it is a dimension or if it is a mental space in our head that needs to be broken,” he says. “There is some confusion that I see when good art is broken that kind of feels right or kind of feels uncomfortable. I feel this world is broken and I need to break something to fix it.”