From the Whitney Museum to Fort Worth, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith provokes conversations about Indigenous peoples and transforms the contemporary art canon with her long-overdue career retrospective.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map

October 15, 2023 – January 21, 2024

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

In the first retrospective of an Indigenous artist to be organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s body of work breaks the so-called “buckskin ceiling,” as the artist likes to say. Recently opened at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map consists of 130 paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures made over the last five decades.

The exhibition shows how Smith, an enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, interprets contemporary life in the U.S. through Native iconography that provokes conversations about land, climate change, cultural preservation, generational trauma, and the ongoing challenges that Indigenous peoples face in this country.

Ultimately, Smith is a storyteller. “These are my stories, every picture, every drawing is telling a story. I create memory maps.” Her works play with familiar icons and imagery—trade canoes, bison, maps, flags—and flips the script, sometimes through satire and humor.

From the beginning, since the 1970s, Smith was quietly engaged in politics in her work. When she desired to make her voice louder, Smith began to incorporate text. As a child, her father told her to never criticize white people. So she uses newspaper clippings in her paintings as a way to subvert the aggression.

Each work is politically charged and full of layers, rewarding viewers for close, prolonged looking. For example, her map paintings are imbued with active language cut from newspapers to make a statement about recording memory and Native peoples: “we are everywhere.” The map continues to be a tool for Smith in her work today, now turning the image on its side in order to disorient viewers’ expectations and understandings of our position in this landscape.

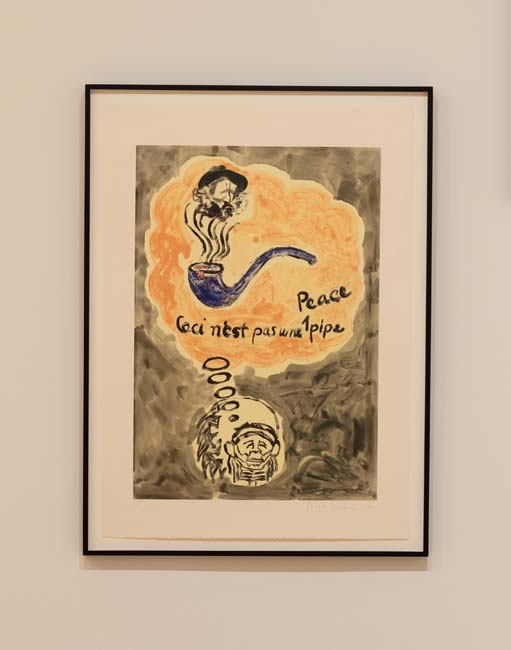

Having studied art at Framingham State College in Massachusetts and University of New Mexico, Smith learned the Western and Eurocentric art historical canon, off of which she riffs for her own means. Thus looking through a series of prints that feature an image of General Custer—the stand-in figure for the genocide of Plains Indians in the 19th century—viewers can find the mischievous ways in which Smith references well-known artists like René Magritte, Georg Baselitz, Robert Rauschenberg, or Willem de Kooning.

Despite the many art historical influences, Smith’s work defies categorization. Likewise, Smith herself doesn’t fit into one box. She is an artist, educator, activist, curator, and advocate for her Native community. In the early 1980s, she curated the first traveling exhibition of contemporary art by Native American women, Women of Sweetgrass, Cedar and Sage. And today, Smith curated an exhibition currently on display at the National Gallery of Art of a group of nearly fifty living Native artists practicing across the U.S.

Smith subscribes to the broad belief that one has to understand and respect history in order to imagine new futures. While many of her works in Memory Map show a world that is full of racism, trauma, and pain, she also makes space for Indigenous empowerment, tradition, and the restorative power of kinship. With her retrospective currently on view in a state where much of the Indigenous population was once decimated or driven out, Smith’s work helps us to imagine a world wherein Native peoples no longer have to fight to be seen.