The new book Making History: IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts shows how IAIA is redefining boundaries in Native art scholarship.

Making History: IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (University of New Mexico Press, 2020) is a book primarily written by and for Indigenous curators, scholars, and educators. The volume—both textbook and scholarly work—is not only a necessary contribution to contemporary Indigenous art history but is foundational to the canonization of the study and teaching of Native art.

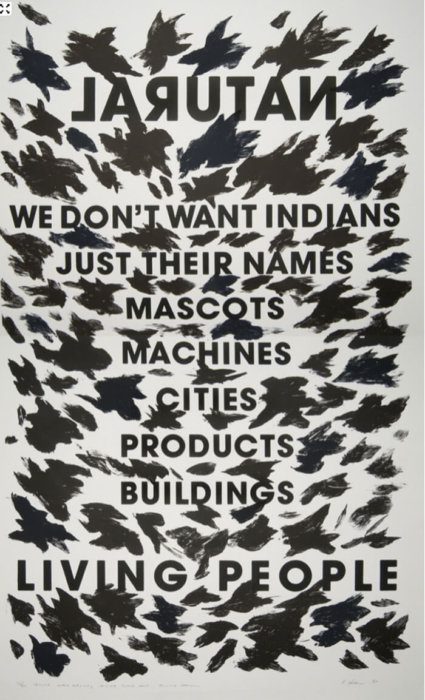

Edited by Nancy Marie Mithlo (Chiricahua Apache), the book constructs an “American Indian Curatorial Practice,“ through which Native scholars and artists can develop a framework for understanding Indigenous art practices, discourses, and movements. Fundamentally, American Indian Curatorial Practice is “long-term, mutually meaningful, reciprocal, and with mentorship.” This important framework—meant to Indigenize and perhaps decolonize—underpins Making History.

Making History begins with a brief introduction to the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (MoCNA), and to the IAIA archival collections. As many New Mexicans know, IAIA is the only tribal college in the United States solely dedicated to advancing American Indian art, and its associated museum, MoCNA, is the only museum in the world solely committed to contemporary Indigenous art. Making History is firmly situated within IAIA, and in turn, the book approaches Native art through the lens of the Indigenous scholars and artists leading the institution. Indeed, Tatiana Lomahaftewa-Singer (Choctaw/Hopi) and Ryan S. Flahive tell us that IAIA’s teaching philosophy emphasizes “cultural difference as the basis for cultural expression,” an ethos also embedded throughout the volume. This opening chapter sets the tone: broad-ranging essays and stunning images are accompanied by a careful selection of external resources, gently guiding the reader towards further research.

Making History is firmly situated within IAIA, and in turn, the book approaches Native art through the lens of the Indigenous scholars and artists leading the institution.

Thematically organized, subsequent chapters deal with overarching themes within the history of Native art. Ranging from “Depictions of the Body and Nudity,” authored by Mithlo, to “Mapping Indigenous Space and Place,” by John Paul Rangel (Apache/Navajo/Spanish), and “Presentations and Representations: Images of Dance from the Southwest and West,” by Suzanne Newman Fricke, each chapter positions IAIA as the center of the contemporary Indigenous art movement.

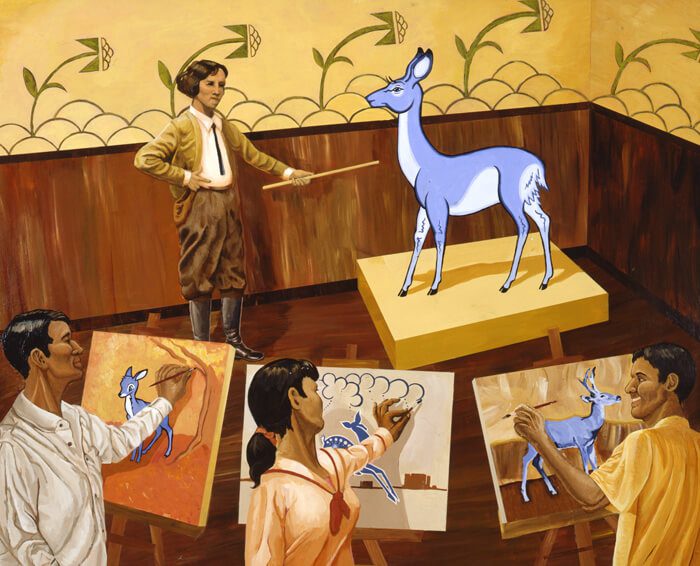

Uniquely, the chapters also provide instruction on how to read visual art through distinctly Indigenous methodologies and epistemologies. Each section includes teaching resources ranging from vocabulary lists and bibliographies to exhibition proposals and reviews, to library scavenger hunts and artist biographies. In particular, after Lara M. Evans (Cherokee) traces the trajectory of Native arts scholarship and posits the eventual diversification of the art historical canon, her chapter, “Transforming Art History in the Classroom,” holds an immense amount of methodological suggestions and pedagogical instruction.

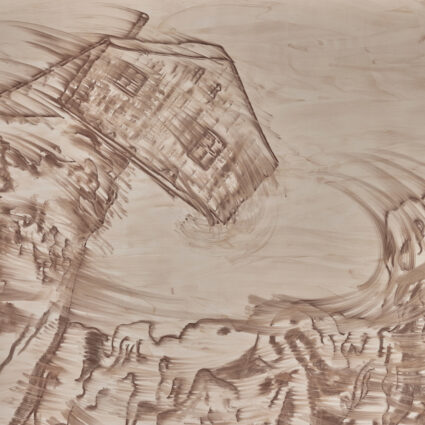

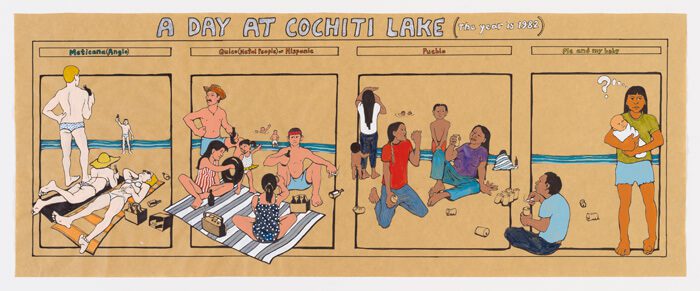

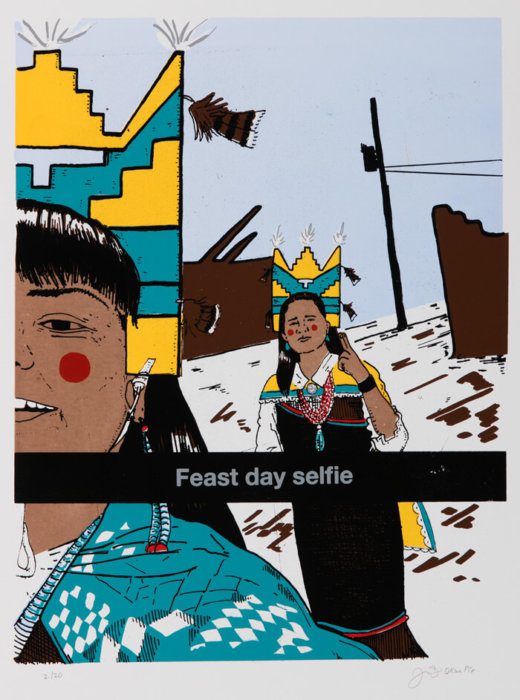

Next, John Paul Rangel expertly deals with American Indian concepts of place and space, where “land serves as a container and marker of culture,” and through which space is Indigenized and activated through community building. Here, Jason Garcia’s (Okuu Pin) (Santa Clara Pueblo) Feast Day Selfie (2016) and Mateo Romero’s (Cochiti Pueblo) Corn Dance Series (1991) are highlighted as examples of how Native artists embed intergenerational knowledge within depictions of place and space, all while using an ethnographic lens. And Suzanne Newman Fricke’s discussion of Indigenous dance uses the work of Allan Houser (Chiricahua Apache), Melanie Yazzie (Diné), and Fritz Scholder (Mission/Luiseño) to explain how visual depictions of movement, dance, music, and ceremony are often physical manifestations of Native cultures.

The impressive volume closes by looking to the future of Indigenous knowledge production and educational pedagogy. David Wade Chambers’s “Teaching from Three Knowledge Spaces” looks at the Native Eyes Project, an Indigenous Studies curriculum that allows for American Indian ontologies to be integrated into mainstream humanities and social sciences. This creates what Chambers calls a “third knowledge space”—a place where the concept of knowledge is indeed the subject. This is, perhaps, the volume’s most important contribution: the construction of a firm epistemological space where diverse and differing ontologies are recognized to have “distinct and heterogenous components that can be compared, shared, joined, interwoven, or torn asunder.”

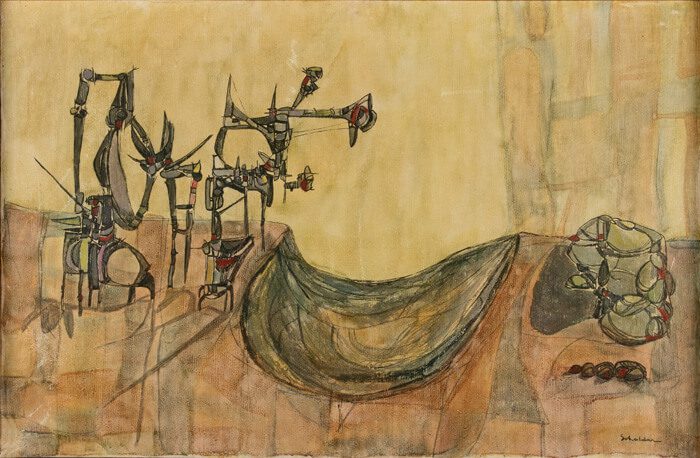

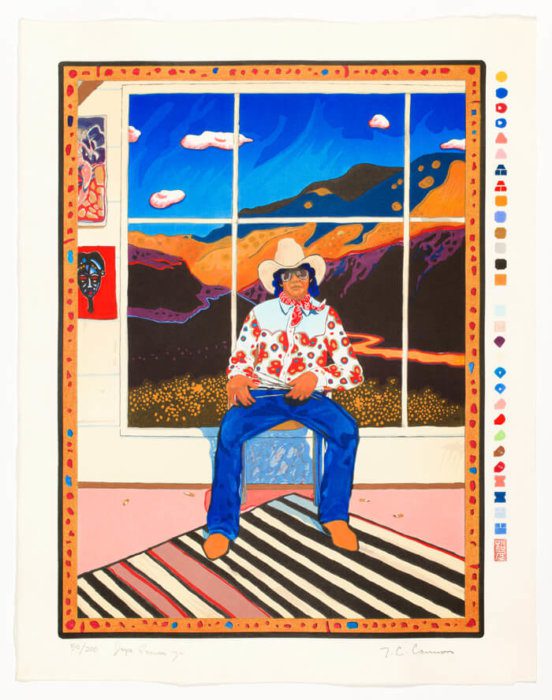

With 102 plates and 86 figures, the book is visually striking. Four gallery inserts are embedded between sections, each creating pseudo-exhibitions of works selected from the Institute’s alumni. Two original poems by Alex Jacobs (Mohawk) and Elizabeth Woody (Navajo/Warm Springs/Wasco/Yakama) bookend the volume. And with its generational approach, Making History is, importantly, often written in the first person, making it clear that the authors are directly speaking about—and are the experts on—themselves. This works against the settler-colonial idea that non-Native curators, writers, and academics are the sole authority on Indigenous art. Making History fosters what Mithlo calls “embedded conversations,” through which “readers should imagine a guide walking a visitor through familiar territory, taking pains not to alienate or lose the guest while also pointing out amazing vistas.”

Blending art and institutional history with practical pedagogical instruction, Making History is a nod towards the futures of academia, museums, and publishing. It reflects Indigenous knowledge systems and is primarily written by American Indian scholars, making it a model for collaborative, nuanced research, and providing a thoughtful entry point for anyone looking to teach or learn about Native art.