Modern Desert Markings at the Barrick Museum of Art in Las Vegas showcases contemporary takes on Land Art works by Michael Heizer, Walter de Maria, and Jean Tinguely.

Modern Desert Markings: An Homage to Las Vegas Area Land Art

March 14–July 8, 2023

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art, Las Vegas

Modern Desert Markings: An Homage to Las Vegas Area Land Art partially acts as a reclamation project. Ten artists were asked to observe, contemplate, and interpret five historic works of Land Art in the Southern Nevada desert dating to one of the movement’s heights between 1962 and 1970.

The artists, who are based in Nevada and elsewhere, were required to take field trips to various sites while refraining from making their own physical markings. Instead, the artworks—many of which reclaim and recast what one might argue are blemishes on the land—are displayed and contained in the space of the gallery.

Jen Urso’s artwork reacts to Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969), which has eroded and decayed due to nature taking over. Instead of viewing the landscape as a “wasteland,” a belittlement often applied to degrade or erase desert life, Urso’s full-color poster illustration shows the many plants that grow and thrive at the site. The artwork is part of What the Desert Already Has (2023), which continues with a planter and grow lights containing soil Urso collected from Mormon Mesa; little plants have sprouted during the exhibition’s run. These gestures are subtle, intentional efforts to mend the open wounds left behind by the large-scale, earth-destructive Double Negative.

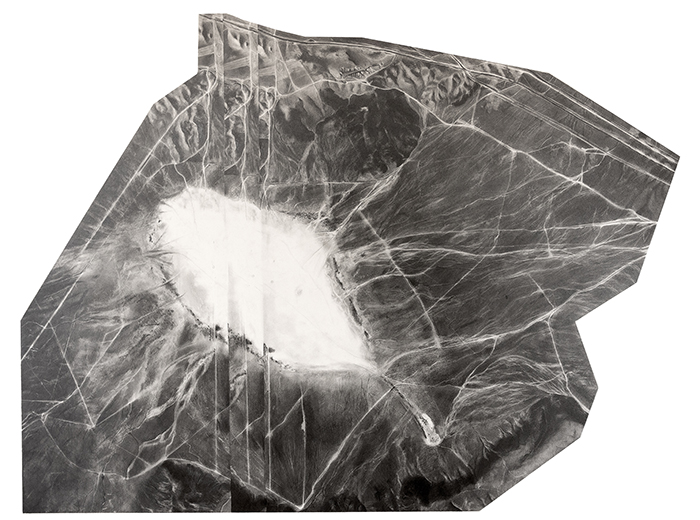

Mark Brest van Kempen reacts to Walter de Maria’s Las Vegas Piece (1969), a mile-long square etched into the earth that’s also been reclaimed by nature, with Las Vegas Piece Piece (2023). Brest van Kempen’s work—an installation of botanical signs, drawings, and photographs that remaps the boundaries of de Maria’s engraving—is an opening salvo to his deeper dive on environmental injuries and healing, an investigation that speaks to the temporary quality of human alterations compared to nature’s overriding forces.

Elsewhere, Marisa J. Futernick’s Mirage (2023) explores the region’s complicated sociopolitical histories when it comes to the land. Futernick’s video, poetically narrated and told through the artist’s rapturous still images, exposes the desecration, commodification, and governmental experimentation (atomic testing, mining) of the desert. “People can disappear out here,” says Futernick in the twenty-four-minute-plus piece. “Things disappear, too. Stories. Histories. Species. Money. Time. Rights.”

The approach by show co-curators Katie Hoffman, president of Nevadans for Cultural Preservation, and University of Nevada, Las Vegas art history instructor and Southwest Contemporary contributor Hikmet Sidney Loe steered artists towards inquiry and scrutiny—rather than celebration or homage (though “homage” is in the exhibition title)—of works in the Land Art canon.

As a result, the leave-no-trace artists—who reply to Land Art’s legacy with careful, critical, and even protective eyes—provide unique and hopeful takes while recasting the idea of Land Art into something more expansive and harm-reductive. For instance, Emily Budd’s sculptures made of materials found at Jean Dry Lake—the site of ephemeral works by Michael Heizer and Jean Tinguely—rebuild “worlds through queer renewal and repair.” Keeva Lough’s piece, which recreates documentation photographs of Tinguely’s Study for an End of the World No. 2 (1962), illustrates in a non-intrusive manner that there’s often an agenda imposed on the land. The participating artists in the exhibition make their desert markings in more conscious, sustainable ways.